A Bank Check Tour of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

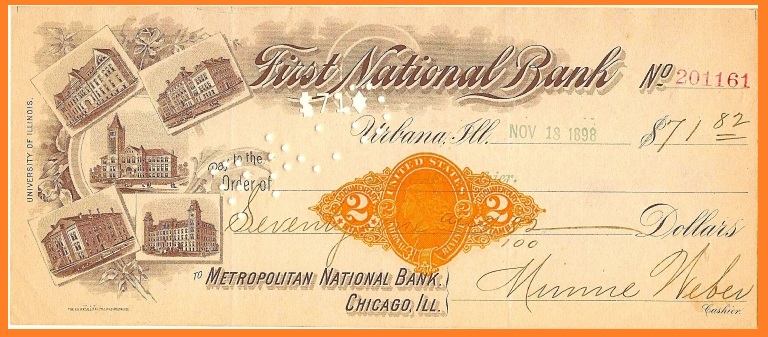

A LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY VISITOR to University of Illinois’s Urbana campus, clutching this bank check, would have had little difficulty matching its montage of building vignettes to their corresponding structures. Not only did these five buildings comprise the major landmarks of the Urbana campus at the time, they all fronted a short segment of West Green Street and could have been discovered within just a few minutes’ walk. As an architectural guide, the check’s only inconvenience is that it doesn’t give the buildings’ names. One hundred and twenty-five years later, a similar visitor to the campus would have much more difficulty identifying the five buildings on this check since, with the passage of time, they have been renovated and even demolished. Moreover, serving roughly ten times the number of students now that it did back then, the physical campus itself has become a much larger and more complicated environment to navigate.

Fortunately, one resource exists that makes identifying these building vignettes fairly straightforward: the enormous supply of period postcards that Americans once relied upon to document the monuments of their daily lives. Many of these postcard images date from years when the check was issued, featuring renditions of buildings whose exteriors may have since been modified, whose names and purposes have changed, or which may no longer exist. Indeed, two alumni of the university, Willis C. Baker and Patricia L. Miller, actually produced a little guidebook entitled History in Postcards: Champaign, Urbana, and the University of Illinois that provides a convenient reference for putting names to facades. That book, along with the trove of postcard images available from various online sources, makes it possible to turn this bank check into a brief architectural tour of the University of Illinois as it appeared around the year 1900.

From Illinois Industrial University to University of Illinois

One of thirty-seven land-grant institutions arising out of the Morrill Act of 1862, the original name “Illinois Industrial University” reflected the prevailing educational ethos that such institutions should aim to provide a utilitarian training in either agriculture or the mechanic arts. Like its sister institutions in other states whose names originally included the term “Agricultural”, the school struggled to shed that qualifier in its name as its curriculum evolved in a more comprehensive direction. Moreover, as the university’s historian Winston Solberg noted, the word “Industrial” in its title encouraged an unfortunate misapprehension among the public, which "interpreted it to mean either a reformatory or a charitable institution in which compulsory manual labor figured prominently.” As a result, the university regularly received letters from aroused citizens recommending that one juvenile miscreant or another be ‘admitted’ to the institution. The institution succeeded in changing its name to “University of Illinois” in 1885. The coda “at Urbana-Champaign” came into use during the early 20th century but wasn’t officially adopted until the 1960s.

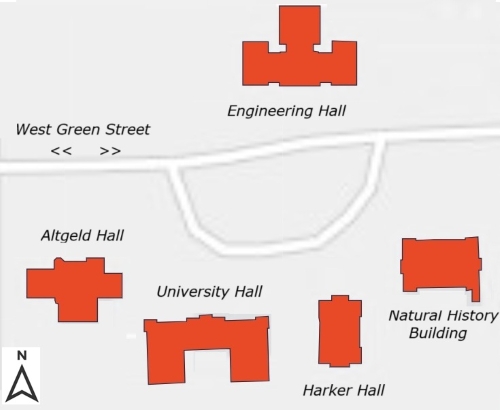

Founded in 1867, during its first decades the University of Illinois experienced the indifference and recurrent suspicion of the state’s General Assembly (legislature) which, dominated by rural interests, had little desire to give professors money that might be frittered away on curricula beyond a practical A&M core or, worse, the liberal arts. During these years the campus made for an unprepossessing visit. The combined population of Champaign-Urbana was about 11,000 and featured few brick-paved roads. In Solberg’s words, “heavy rains often converted the treeless, swampy plain into an undrained, mosquito-ridden swamp.” Some 700 students were enrolled at the university by the turn of the century. At this point in time, the heart of the campus ran east to west along Green Street; only during the 20th century did the university expand in a north-south direction, acquiring the enclosed, grassy quadrangles that are the typical layout of modern colleges and universities.

During the years in which this bank check would have been used, the university’s built environment was influenced by three people in particular: Andrew Sloan Draper, President of the university from 1894 to 1904; John Peter Altgeld, Governor of Illinois from 1893 to 1897, and Nathan Clifford Ricker, a professor of architecture and engineering who ran both departments for decades before retiring in 1906. A strong, somewhat autocratic personality, Draper modernized the university’s operations and expanded its facilities. He also exercised heavy-handed control over the faculty and was skeptical of their pretentions to engage in research. Although from Chicago and the first Democratic Governor since the university’s founding, Altgeld had a Jeffersonian reverence for higher education as a means to uplift and expand the capabilities of the common man. After his election in November 1892 Altgeld proved to be a great friend of the university and a supporter of its interests at the state capital. Even more than loosening purse strings in Springfield, Altgeld encouraged a more sympathetic view by the Democratic party of educational institutions whose governance had been previously dominated by Republicans. Altgeld also had decided tastes in architecture that ran towards the Tudor-Gothic (towers, spires, turrets), preferences which he did not refrain from imposing on educational building programs across the state.

Finally, the professor and architect Nathan Ricker had the most profound impact on how the University of Illinois actually looked during its early decades. The first graduate of any American architecture program in the country, Ricker immediately joined the University of Illinois faculty and subsequently shaped the practice of American architecture through the cohorts of students that he trained and influenced. Distinctive to his approach to architectural education was his conviction that the practices of architecture and engineering ought to be bound tightly together. Ricker and the students he trained had their hands on four of the five buildings featured on this check (as well as other structures across campus) not only with their design but also with the practical aspects of their construction.

ABOVE: The approximate location of the five buildings featured on the check, with reference to West Green Street. Of the five buildings, University Hall no longer exists, having been demolished in 1938 and replaced by the Illini Union (Map adapted from University of Illinois Campus Buildings Timeline, at: https://univofillinois.maps.arcgis.com/.) BELOW: The "three towers" view. Looking westward, most likely from the Natural History Building. Harker Hall is in the foreground, University Hall towards the center, and Altgeld Hall in the distance off to the right (Image source: eBay).

A Tour by Bank Check

Our virtual tour of the five building vignettes depicted on this check, illustrated by their corresponding postcards, begins with building at the center of the montage, then proceeds clockwise from the top left for the other four buildings.

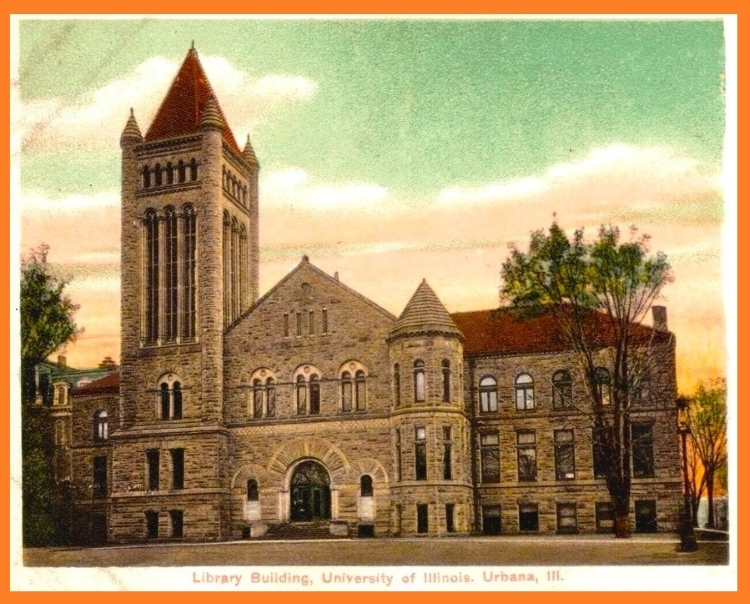

Altgeld Hall (1897)

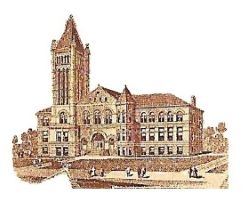

Known originally as the University Library, this building was completed in December 1897 (given that the check above is  dated November 1898, this gives a very definite idea of when the First National Bank adopted this check design). The later name, Altgeld Hall, was a nod to the governor’s original influence over the building project. A fan of Gothic architecture. Altgeld inserted himself forcefully into the design process, obliging the building committee (which had preferences for something Grecian) to abandon an initial plan that had been awarded first prize in a design competition. Altgeld's pressure, abetted by Draper, then led the committee to stiff a second alternative submitted by the prestigious Chicago firm D. H. Burnham. Somewhat flummoxed, the committee turned in-house to Professor Ricker and his colleague James M. White, who quickly whipped up a plan inspired by the Romanesque Revival style (lots of rounded window and entryway arches, rounded towers) associated with the American architect Henry Hobson Richardson, his signature building being Trinity Church in Boston. Constructed of pink limestone from the Kettle River quarry of Minnesota and topped with a red tile roof, University Library (later Altgeld Hall) became known as one of five “Altgeld’s Castles” –buildings in public universities across the state where the governor succeeded in imposing his tastes.

dated November 1898, this gives a very definite idea of when the First National Bank adopted this check design). The later name, Altgeld Hall, was a nod to the governor’s original influence over the building project. A fan of Gothic architecture. Altgeld inserted himself forcefully into the design process, obliging the building committee (which had preferences for something Grecian) to abandon an initial plan that had been awarded first prize in a design competition. Altgeld's pressure, abetted by Draper, then led the committee to stiff a second alternative submitted by the prestigious Chicago firm D. H. Burnham. Somewhat flummoxed, the committee turned in-house to Professor Ricker and his colleague James M. White, who quickly whipped up a plan inspired by the Romanesque Revival style (lots of rounded window and entryway arches, rounded towers) associated with the American architect Henry Hobson Richardson, his signature building being Trinity Church in Boston. Constructed of pink limestone from the Kettle River quarry of Minnesota and topped with a red tile roof, University Library (later Altgeld Hall) became known as one of five “Altgeld’s Castles” –buildings in public universities across the state where the governor succeeded in imposing his tastes.

Highlights of its interior are a series of spectacular murals painted by the art professor Newton Alonzo Wells that commemorate thematically the four colleges which comprised the university at that time. Functioning as the university’s library until 1927, the building was then given over to the law school, which occupied the building until mid-century, when it was taken over by the Mathematics Department.

While, over the decades, Altgeld Hall has been expanded with four different additions, the northward-facing original building with its distinctive carillon tower has retained its original look, representing, in the words of a tribute on the occasion of the building’s centenary, “a statement to the world that the barely thirty year old land grant institution was no longer a ‘cow college’, but an institution of higher education in the ranks of the select.”

Natural History Building (1892)

Also designed by Nathan Ricker, the Natural History Building is an example of the High Victorian Style, an archi tectural variant that was also favored for public and commercial buildings in late 19th century America. Placed just to the east of Harker Hall, Natural History was dedicated in 1892. The original building was rectangular with its front entrance facing north onto Green Street, As it underwent a series of additions, by 1923 the building’s access was reoriented towards the quadrangle to the south, which had become the new focal point of the campus.

tectural variant that was also favored for public and commercial buildings in late 19th century America. Placed just to the east of Harker Hall, Natural History was dedicated in 1892. The original building was rectangular with its front entrance facing north onto Green Street, As it underwent a series of additions, by 1923 the building’s access was reoriented towards the quadrangle to the south, which had become the new focal point of the campus.

Like Engineering Hall, since its original construction this building has remained dedicated to disciplines relating to the Earth sciences. Renovated in 2017, Natural History currently houses the School of Earth, Society, and Environment, and its three constituent departments--Geology, Geography, and Atmospheric Sciences.

Engineering Hall (1894)

Construction of Engineering Hall was another project into which Governor Altgeld inserted himself, although in this instance  not to push his architectural tastes. Facing a swelling student population and acute shortages of building space for many programs, the university submitted a request in 1893 to the General Assembly for funds to cover operating expenses and three new buildings: engineering, a library, and a museum. Having just provided funds in 1891 for the Natural History Hall, legislators were unsympathetic to any further construction monies until Altgeld interceded to get fellow Democrats in Springfield to provide at least for engineering.

not to push his architectural tastes. Facing a swelling student population and acute shortages of building space for many programs, the university submitted a request in 1893 to the General Assembly for funds to cover operating expenses and three new buildings: engineering, a library, and a museum. Having just provided funds in 1891 for the Natural History Hall, legislators were unsympathetic to any further construction monies until Altgeld interceded to get fellow Democrats in Springfield to provide at least for engineering.

Finished in November 1894, the design for Engineering Hall was chosen in a competition limited to submissions from graduates of University of Illinois (practically, this meant all had to be students of Ricker). George Wesley Bullard, class of 1882, won with a Renaissance Revival design with an exterior of white sandstone for the first floor and orange brick above that. The orange of the brick, along with the building’s blue roof were evocative of the university’s official colors, which had been decided upon that same year.

Engineering Hall was the first campus building dedicated to a single college and, of the five buildings, its appearance has changed the least over time apart from some renovations in 1998.

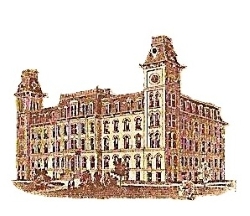

University Hall (1873)

Of the five buildings illustrated on this check, University Hall is the only one in which Nathan Ricker or his students had no  hand in designing (Ricker had only just earned his architecture degree the same year University Hall opened). This is also the only building featured on the check which no longer exists. Originally known as the New Main Building, University Hall was completed in 1873 to replace the Old Main Building and served as a multi-purpose center of university life—classrooms, lecture halls, administrative offices, and the library on the second floor. Designed by the Chicago architect John Mills Van Osdel in the imposing Second Empire style that had become broadly popular for American public buildings, University Hall featured twin towers and the typical mansard roof with dormer windows. Its original construction took place under precarious financial circumstances. Buffeted by the recovery costs of the Chicago Fire (1871) followed by the economic downturn caused by the Panic of 1873, the Illinois General Assembly reneged on its funding commitments for the building, leading the university to pay for construction by plundering its endowment (which the legislature never reimbursed).

hand in designing (Ricker had only just earned his architecture degree the same year University Hall opened). This is also the only building featured on the check which no longer exists. Originally known as the New Main Building, University Hall was completed in 1873 to replace the Old Main Building and served as a multi-purpose center of university life—classrooms, lecture halls, administrative offices, and the library on the second floor. Designed by the Chicago architect John Mills Van Osdel in the imposing Second Empire style that had become broadly popular for American public buildings, University Hall featured twin towers and the typical mansard roof with dormer windows. Its original construction took place under precarious financial circumstances. Buffeted by the recovery costs of the Chicago Fire (1871) followed by the economic downturn caused by the Panic of 1873, the Illinois General Assembly reneged on its funding commitments for the building, leading the university to pay for construction by plundering its endowment (which the legislature never reimbursed).

Together with Altgeld Hall, the profile of University Hall created the “three towers” effect (see postcard above) that defined the campus’s skyline until the latter building’s demise in 1938. Fundamentally, the building’s fate was determined by deferred maintenance: debates about the building’s renovation dragged on inconclusively, only to be decided in January 1938 when, after a portion of the roof caved in, the building was declared a hazard and forthwith demolished. In its place rose the Illini Union, completed in 1941.

Harker Hall (1878)

Designed by Ricker in the Second Empire style with a mansard roof, this building began life as the Chemistry Laboratory in  1878. The university trustees required that the Chemistry Laboratory be constructed in the same Second Empire style as University Hall. Harker Hall was built adjacent to University Hall and, likewise, looked north onto Green Street (the quadrangle to the south was a later development). Ricker’s students were heavily involved with the construction of the building. A fire in the building caused by a lightning strike in August 1896 destroyed the mansard roof, which was replaced by one with a more conventional pitch. In 1902 the building was repurposed for the new College of Law, which occupied the building for the next twenty-five years until it relocated to the University Library building (now Altgeld Hall). Thereafter, the building was home to the Departments of Entomology and Botany. In 1941, the building acquired its present name, Harker Hall, in honor of Oliver A. Harker, Dean of the College of Law from 1902 to 1916. Obsolete for instructional purposes, the building was spared the wrecking ball and, after complete renovation (including restoration of the original mansard roof) became the offices of the University of Illinois Foundation in 1992.

1878. The university trustees required that the Chemistry Laboratory be constructed in the same Second Empire style as University Hall. Harker Hall was built adjacent to University Hall and, likewise, looked north onto Green Street (the quadrangle to the south was a later development). Ricker’s students were heavily involved with the construction of the building. A fire in the building caused by a lightning strike in August 1896 destroyed the mansard roof, which was replaced by one with a more conventional pitch. In 1902 the building was repurposed for the new College of Law, which occupied the building for the next twenty-five years until it relocated to the University Library building (now Altgeld Hall). Thereafter, the building was home to the Departments of Entomology and Botany. In 1941, the building acquired its present name, Harker Hall, in honor of Oliver A. Harker, Dean of the College of Law from 1902 to 1916. Obsolete for instructional purposes, the building was spared the wrecking ball and, after complete renovation (including restoration of the original mansard roof) became the offices of the University of Illinois Foundation in 1992.

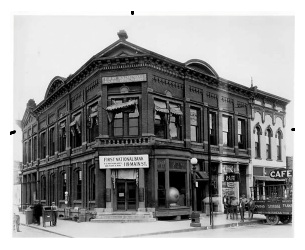

The First National Bank of Urbana and Cashier Minnie Weber

Finally, a few words about the bank and its check. Founded as the private bank of Gardner, Burpee, and Curtiss, it took on  a national charter (no. 2915) and became the First National Bank of Urbana in 1883. Architecturally, the bank’s building as it appeared in the early years of the 20th century (see picture) was thoroughly unremarkable. Unusual, in contrast, was the fact that Minnie Weber, who signed the check, was one of the few female cashiers working within the national banking system. Even more unusual was that she got the job not by being the spouse or relative of a male banker, but on her own terms. The daughter of a barber from Germany, Minnie was born in New York City but moved with the family at an early age to Illinois. She began working as a bookkeeper at the Urbana grocery store of M. E. Monnett before taking a similar job at the bank in 1886, moving up to assistant cashier in 1892 and then cashier by 1896, replacing Andrew F. Fay, who left to take a diplomatic post in Spain. In 1900 Minnie resigned from the bank after marrying Morton McCown, a clerk at the clothing store Ottenheimer Brothers (later Kaufman’s). The couple resided in Champaign for the rest of their lives. Morton McCown continued in haberdashery, becoming known over the years to thousands of male students for helping with their collegiate sartorial choices.

a national charter (no. 2915) and became the First National Bank of Urbana in 1883. Architecturally, the bank’s building as it appeared in the early years of the 20th century (see picture) was thoroughly unremarkable. Unusual, in contrast, was the fact that Minnie Weber, who signed the check, was one of the few female cashiers working within the national banking system. Even more unusual was that she got the job not by being the spouse or relative of a male banker, but on her own terms. The daughter of a barber from Germany, Minnie was born in New York City but moved with the family at an early age to Illinois. She began working as a bookkeeper at the Urbana grocery store of M. E. Monnett before taking a similar job at the bank in 1886, moving up to assistant cashier in 1892 and then cashier by 1896, replacing Andrew F. Fay, who left to take a diplomatic post in Spain. In 1900 Minnie resigned from the bank after marrying Morton McCown, a clerk at the clothing store Ottenheimer Brothers (later Kaufman’s). The couple resided in Champaign for the rest of their lives. Morton McCown continued in haberdashery, becoming known over the years to thousands of male students for helping with their collegiate sartorial choices.

.....

REFERENCES

“Altgeld Hall, Centennial Celebration” [brochure], June 16, 1997 ("cow town" quote).

Brochure available online at: https://math.illinois.edu/system/files/inline-files/centennial_brochure.pdf

The Bankers’ Magazine, April 1892, p. 823; February 1896, p. 233 (Minnie Weber's career).

Champaign Daily Gazette, Oct 21, 1885; Jan 16, 1896; July 18, 1900 (Minnie Weber's career).

Scheinman, Muriel, “Altgeld Hall, the Original University Library Building at the University of Illinois: Its History, Architecture, and Art” M. A. Thesis (University of Illinois, 1969), esp. pp. 14-19 on Governor Altgeld's intervention.

Thesis available online at: https://math.illinois.edu/system/files/inline-files/scheinman_thesis_0.pdf

Solberg, Winston U. The University of Illinois 1867-1894: An Intellectual and Cultural History (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1968), “industrial university” quote p. 227.

Solberg, Winston U. The University of Illinois 1894-1904: The Shaping of the University (Urbana: University of Illinois, 2000).

The Woman’s Column (Boston, MA), February 29, 1896 (notice of Winnie Weber’s appointment as cashier).

“University Hall (1871-1938)”

https://www.library.illinois.edu/slc/2016/09/15/university-hall-1871-1938/