Politics and Paper Money

The Bettor Deal Certificate and McNair’s Federal Fealty Note

MUCH OF THE POLITICAL OPPOSITION to President Lyndon Baines Johnson emerged from the sequence of fateful policy choices concerning inflation and the Vietnam War that he made between 1964 and 1967. In addition, LBJ faced hostility for two further reasons: his checkered past in Texas politics well before his ascent to national prominence and the Southern backlash against his commitments to civil rights and expanded welfare programs. These two reasons gave rise to two further examples of political scrip considered here, the Bettor Deal Certificate and McNair’s Federal Fealty Note.

The Bettor Deal Certificate (1964)

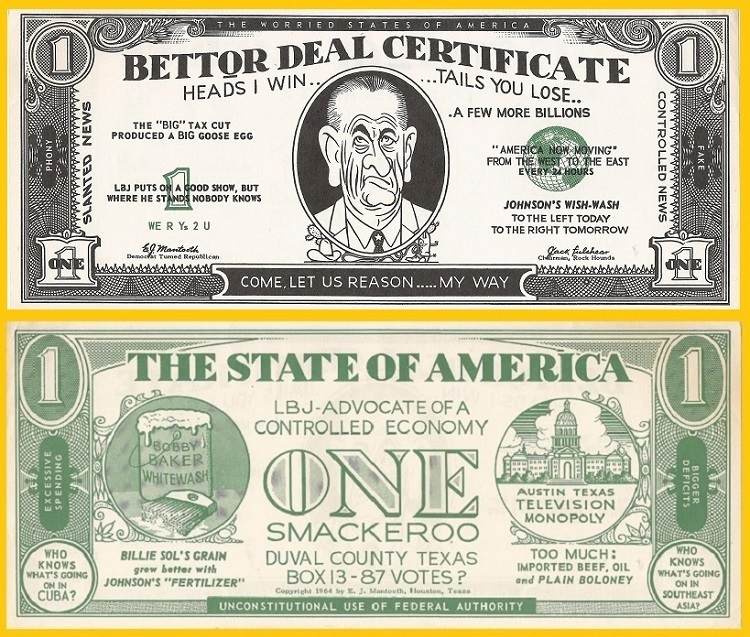

The “Bettor Deal Certificate”, was an anti-Johnson piece of currency satire produced by two Texans, E. J. Mantooth and Graves Nellis “Jack” Fulshear, whose signatures appear on the front of the note. Though undated, it was copyrighted by Mantooth in 1964, before the Great Society became Johnson’s defining agenda.

The Houstonians E. J. Mantooth and Jack Fulshear produced this "Bettor Deal Certificate" in 1964.

Based in Houston, Mantooth and Fulshear were responsible for a number of currency-like political parodies over the years, all attacking Democrats, beginning with a pair of notes lampooning President Harry Truman in 1952. Of the pair, Edwin James Mantooth (Jr.) was probably responsible for executing the design of the notes. Grandson of Judge E. J. Mantooth, a prominent jurist (and national banker) in Lufkin, Texas, the younger Mantooth worked as an artist first with the Houston Chronicle in the 1930s and later for the Houston Post. Jack Fulshear worked in advertising and direct mail marketing before running his own printing concern.

Satirical currency of any sort at this time faced scrutiny by a vigilant Secret Service alert to the slightest threat of counterfeiting, no matter how implausible or hypothetical. The Mantooth-Fulshear currency parodies were much larger than regular bills and for that reason should have been less problematic from the authorities’ point of view. Nonetheless, the pair did tangle with the law briefly in 1952 before their products passed muster. In contrast, another Houston printer at the time, Leo Kaiser of Premier Printing, produced large quantities of novelty notes on all sorts of themes without incident, possibly because Kaiser eschewed Mantooth’s and Fulshear’s hard-edged political messaging, infusing his own notes with large amounts of cornpone humor instead.

The Bettor Deal Certificate pictured here expresses much generic criticism of the Democratic President. Noteworthy, perhaps, is that Johnson’s large ears, a frequent target of caricaturists, assume here nearly elephantine proportions. The caption, "Come, Let Us Reason ... My Way" is a dig against Johnson's professed affection for that biblical verse from Isaiah 1: 18-19, which begins "Come now, let us reason together..." When Johnson wanted anything bad enough from another person, his perusasive techniques were famously anything but reasonable, subjecting his target to what journalists called "The Treatment":

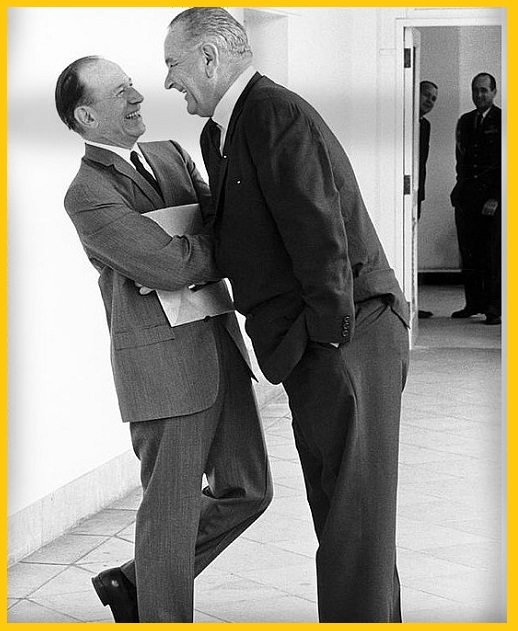

LBJ subjecting Judge Abe Fortas to "The Treatment", 1965 (Source: LBJ Library).

Amid the partisan clutter on the Bettor Deal Certificate, a few features on its reverse merit explanation:

“Bobby Baker Whitewash” refers to the inconclusive investigative into the unsavory activities of Bobby Baker, Lyndon Johnson’s secretary, fixer, and procurer for politicans when Johnson was Majority Leader of the U.S. Senate.

“Billie Sol’s Grain…” refers to Billie Sol Estes, a convicted swindler and Johnson associate whose two big fraud schemes involved anhydrous ammonia (fertilizer) and cotton land financing in Texas.

“Duval County Texas / Box 13-87 Votes?” refers to the infamous 1948 Texas senate primary election between Johnson and Governor Coke Stevenson. In Duval County, Johnson was declared the winner by an improbably large 4622 to 40 vote margin. “Box 13” refers to the notorious ballot box #13 from the town of Alice, Texas, that miraculously produced enough ballots to give Johnson a final 87-vote margin of victory in that contest. The actual box and the ballots it contained have never been found.

“Austin Texas Television Monopoly” refers to the Johnsons’ ownership of a television station in Austin, Texas, which served as the basis for his family’s fortune. Through his wife Lady Bird Johnson, the family controlled the lucrative radio, and later television, station KTBS that benefited from Johnson’s influence, first as Senator and later as occupant of the White House, over the regulatory oversight exercised by the Federal Communications Commission. The value of the television franchise in particular was enhanced by the fact that KTBS operated as a monopoly in the Austin market until 1965.

In the same year this note appeared, a convenient compilation of Johnson’s sleazy political history was published by J. Evetts Haley in the form of a book entitled A Texan Looks at Lyndon: A Study in Illegitimate Power. Indeed, the sum total of what appears on the “Bettor Deal Certificate” can be seen a gloss of that screed’s contents.

Haley, a Texas author and activist who was colorful figure in his own right, represented the segregationist, ultraconservative wing of the Democratic Party that had become marginalized by the rise of the New Deal coalition in the 1930s. Thirty years later, Haley and other disaffected southerners were increasingly turning to a Republican Party whose small-government philosophy accommodated their hostility towards racial integration and political liberalism. Printed by the millions and distributed by the Goldwater forces, Haley’s book went far beyond documenting Johnson’s corrupt past, painting his support for civil rights and the welfare state as betrayals of the South and of the Republic itself.

No aspect of Johnson’s life, including his penchant for liquor and willingness to dance with “the wife of a negro Congressman” at a White House reception, was off limits in Haley’s indictment. As a result of its racist excesses, the book was panned as propaganda by the mainstream press. Even many Republicans kept their distance from it as a campaign document, although newly minted party members like Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina continued to attack Johnson using the same language of treason and betrayal.

McNair’s Federal Fealty Note (1966)

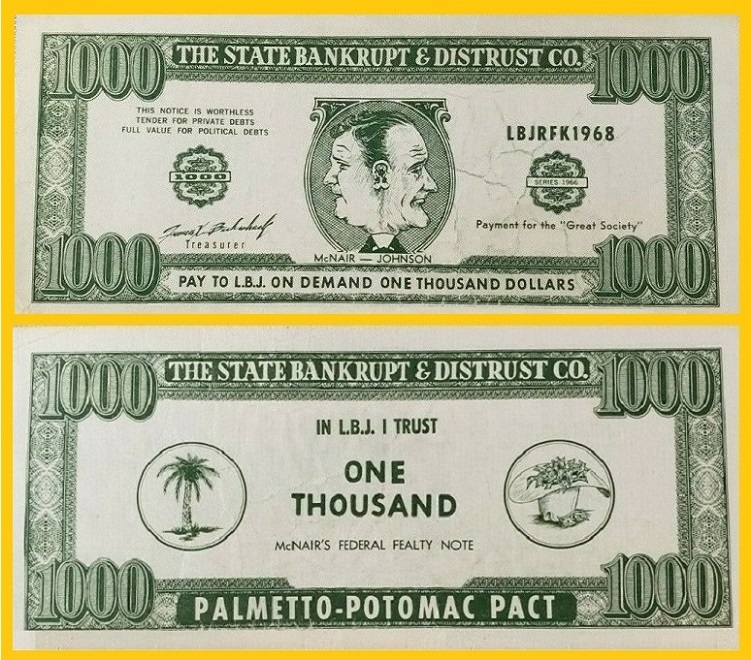

The second piece of anti-LBJ propaganda, “McNair’s Federal Fealty Note”, was a $1,000-denominated parody put out by the Republican Party of South Carolina sometime during August of 1966. Rather than targeting Johnson directly, this note instead addresses the gubernatorial contest that November between the Democratic incumbent, Governor Robert E. McNair, and his Republican challenger Joseph O. Rogers, Jr.

A $1,000 "Federal Fealty Note" used by South Carolina Republicans in the 1966 gubernatorial election.

The note, which overall has a tepid satirical effect, purports to be issued by a clumsily titled “State Bankrupt & Distrust Co.” The front depicts a Janus-face portrait of McNair and Johnson, while the back juxtaposes images of a palmetto and a Texas-style 10-gallon hat (presumably symbolizing Johnson), overflowing with paper money. The arrangement is vaguely reminiscent of the South Carolina state seal. Beneath those images is a reference to a “Palmetto-Potomac Pact.”

Seeking to tie together President Johnson and South Carolina’s Governor McNair, the circumstances of this note’s appearance provide a nice measure of some early tremors of the political earthquake unleashed by Johnson’s victory in 1964. While Goldwater’s loss was numerically decisive, he did manage to take five deep-South states, including South Carolina, as well as his home state of Arizona. Goldwater’s victory in those five states reflected Southern Democrats’ well-understood antipathy towards the national Democratic Party’s embrace of civil rights.

Despite Goldwater’s victory in that state, South Carolina internally remained a Democratic Party bastion. Essentially moribund since the Reconstruction Era, the Republican Party had not even put forward a gubernatorial candidate in nearly thirty years. Nonetheless, Democratic state politicians increasingly kept their distance from their national party as a matter of political survival. In the 1966 election cycle, South Carolina’s Governor McNair faced a Republican challenger in the form of Rogers, a state representative who switched parties in March in order to run against McNair in the general election. Like other state politicians, most notably Senator Thurmond, who had renounced the Democratic Party in 1964, Rogers disavowed his former party’s national support for civil rights and an expanded welfare state.

Campaigning now as a Republican, Rogers sought to take advantage of that tension between the state and the national Democratic parties by tying McNair to Lyndon Johnson. The opportunity to do this came when a report emerged that $1,000 had been donated in McNair’s name to a Johnson campaign entity called the President’s Club. While McNair denied that this had been done with his knowledge, the transaction led to assertions by Rogers that McNair had “a direct line to the White House” and that he stood for “Lyndon Johnson’s ticket in South Carolina.” As piece of campaign literature, the Republicans then had printed up a satirical banknote denominated in the amount of the donation.

As a political misstep, donating funds to a national candidate from one’s own party would hardly seem especially controversial. However, South Carolina Republicans sought to nationalize the contest by making it a referendum on Johnson’s Great Society agenda. Along with the $1,000 note, the Republicans put out a campaign brochure entitled “Had Enuf? News” in which they considered it an attack upon McNair to simply print a photograph of him shaking hands with a black person. While McNair won this contest handily, a decade later the governor’s office passed into the hands of the Republicans, along with the rest of the state.

McNair and his wife, after election victory [left]; McNair with Johnson, 1968 [right]. (Source: Frank Beacham)

Conclusion

The dominant historical narrative of the 1964 presidential election has been governed by two facts: first, that Johnson won that contest in a landslide; and second, that Johnson’s campaign successfully painted Goldwater as an extremist who could not be trusted, especially when it came to nuclear weapons. While both facts are true, they ignore the particulars of Goldwater’s campaign indictment of Johnson.

With nearly sixty years’ hindsight, the references on Mantooth’s and Fulshear’s Bettor Deal Certificate seem like so much inside political baseball, understandable perhaps to anti-Johnson partisans but elusive to a broader audience at the time. However, all of these themes were in general circulation during the 1964 presidential contest between Johnson and Barry Goldwater and were made use of by the latter’s campaign. Indeed, by 1963 investigations of the Billie Sol Estes and Bobby Baker scandals had reached the point where Kennedy was considering removing Johnson from his 1964 re-election campaign. Had Kennedy not been assassinated in November 1963, his Vice President’s political career might have come to a premature end on that humiliating note.

Although their attacks found little electoral traction at the time, Goldwater and his supporters argued, correctly, that Johnson in his personal and professional life was the corrupt product of a corrupt system of Texas politics that was found wanting even by the looser standards of that era. The various references on the Bettor Deal Certificate were all grounded in fact. More damaging, though, to Johnson and to the Democrats was the shift in regional political allegiances stimulated by the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Great Society legislation beginning a year later. McNair’s Federal Fealty Note represents a small piece of early evidence for how Republicans could take advantage of the leftward shift by the national Democratic Party by bringing disaffected southern conservatives into a new national coalition that would come into its own with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980.

REFERENCES

Haley, J. Evetts, A Texan Looks at Lyndon: A Study in Illegitimate Power (Canyon, TX: Palo Duro Press 1964), esp. chs 2-8.

Huntington, John S. “’The Voice of Many Hatreds’: J. Evetts Haley and Texas Ultraconservatism” The Western Historical Quarterly (2017), pp. 1-25.

Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, June 1, 1952.

New York Times, October 8, 1966.

The State (Columbia, SC), October 20, 1966.

The Greenville (SC) News, October 20, 1966.

-----