Bringing Vignettes to Life

Reuben Eaton Fenton, The Soldier’s Friend

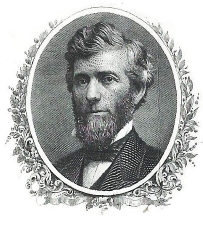

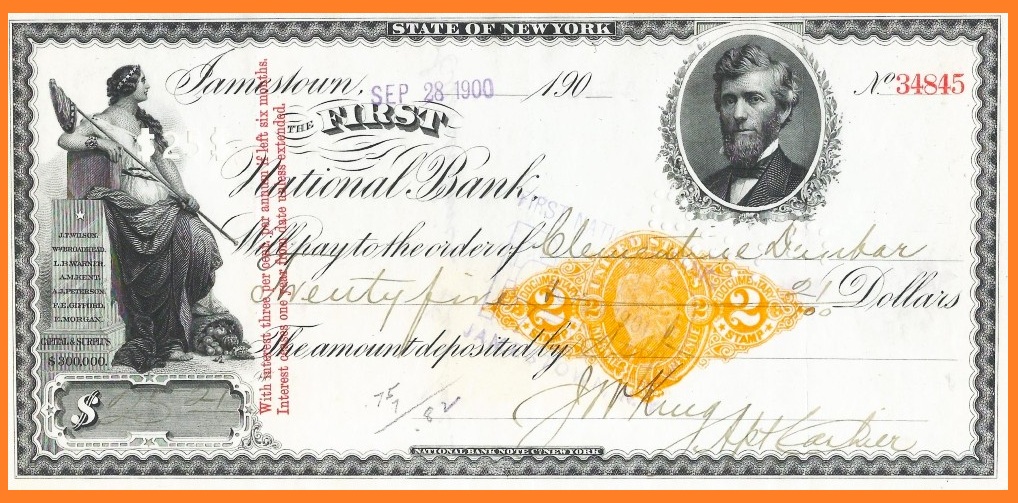

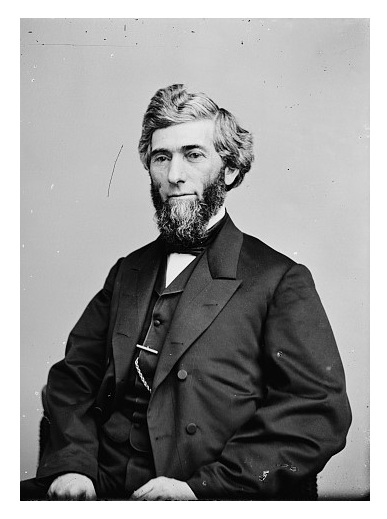

THE TRIM, BEARDED PORTRAIT on this very handsome certificate of deposit issued by the First National Bank of Jamestown, New York needed no caption for the bank’s turn of the century customers. Reuben E. Fenton, President of the bank from 1881 until his death in 1885, was a both a major figure in New York State politics and a formative influence on the Republican Party as it emerged as a national force in the late 1850s. Fenton was elected five times to the U.S. House of Representatives, first as a Democrat and thereafter as a Republican. Resigning from his House seat in 1864 to run for Governor of New York, Fenton served two terms in that office, leaving his mark on state education policy and support for war veterans, the latter issue being a recurrent priority throughout his political career. By prevailing in the gubernatorial contest of 1864, Fenton also played a role in assuring President Abraham Lincoln’s re-election victory that same year.

After two terms as Governor, Fenton was appointed by the state legislature to serve as New York’s senator from 1869 to 1875. Although an early force in the establishment of the Republican Party in New York State, Fenton’s status within the party and influence over President Grant suffered as a result of his rivalry with fellow senator Roscoe Conkling. Indeed, for a time Fenton broke with his party by supporting Horace Greeley’s 1872 presidential campaign on the Liberal Republican ticket. Blocked from further political office as a result, Fenton retired to private life to spend his remaining years as a banker and civic figure in Jamestown.

Early Years

Reuben Eaton Fenton was born on the Fourth of July, 1819, in Carroll, Chautauqua County, New York. The younger son of a merchant who afforded him some amount of formal schooling, Fenton studied law but never entered that profession. Instead, as a young man he prospered in the lumber trade and land speculation (harvesting trees and selling the cleared land to farmers), which thereafter financed a career in politics. Fenton was first elected in 1843 to serve as Supervisor of the town of Carroll before an unsuccessful run for a seat in the New York Assembly. In 1852 Fenton won his first election to the 33rd Congress as a Democrat at the age of 34, making him the youngest member of that body.

Fenton came of age in national politics at a moment when the slavery question began splitting the nation and scrambling political loyalties. A Democrat with “free soil” sympathies (slavery and its spread were bad because it competed with free white labor) Representative Fenton in his maiden speech opposed the repeal of the Missouri Compromise; his later vote against the Kansas-Nebraska of 1854 cost him his re-election that year to a Know-Nothing candidate. Following that defeat, Fenton became an important figure in the emerging Republican Party in New York, chairing its first convention in Syracuse in 1855 and the next year representing his state at the party’s first presidential nominating convention. An amalgam of free-soil and “barnburner” Democrats, abolitionists, Know-Nothings, and northern Whigs, the new Republican Party was bound together by a common antipathy towards slavery, albeit in different intensities and for different reasons. Laid on top of that was the usual jockeying over patronage (jobs) that was typical of American politics of that era. Such was the landscape on which Fenton pursued his political ambitions.

Congressman, Governor, Senator

Returning to electoral competition in 1856, Fenton won back his congressional seat, this time as a Republican, serving from the 35th through the 38th Congress. In an era when oratorical skills were crucial for a career in public life, Fenton was regarded as "a good though not an eloquent speaker and knew the virtue of brevity.” During these eight years Fenton rose to the chairmanship of the Committees on Commerce, Claims, and Invalid Pensions, the latter two roles reflecting his abiding interest in the welfare of the veterans of America’s various wars. Fenton also gained prominence for spearheading congressional investigations of corruption and fraud in military procurement contracting. In 1862 as the Civil War intensified, Fenton became president of the New York Soldiers Relief Association. Prodded by President Lincoln to run for Governor of New York and help carry the state for Lincoln during the 1864 election, Fenton resigned from Congress and campaigned successfully for that post on the motto of “Colonel Fenton, the Soldiers’ Friend” ("Colonel" being his old honorific from the New York State militia).

Reuben Fenton’s two terms as Governor marked the high point of his influence within the state’s Republican Party, control over which he had wrested from Thurlow Weed. He continued to advocate for the welfare of veterans and even fought against draft quotas that he thought were unfair to New York. Other policy achievements included common school funding, agriculture education (chartering Cornell University), and greater help for the disabled. A biographer of Fenton, Helen Grace McMahon, also credits him keeping his nose clean as the saga of the Erie Canal scandals unfolded.

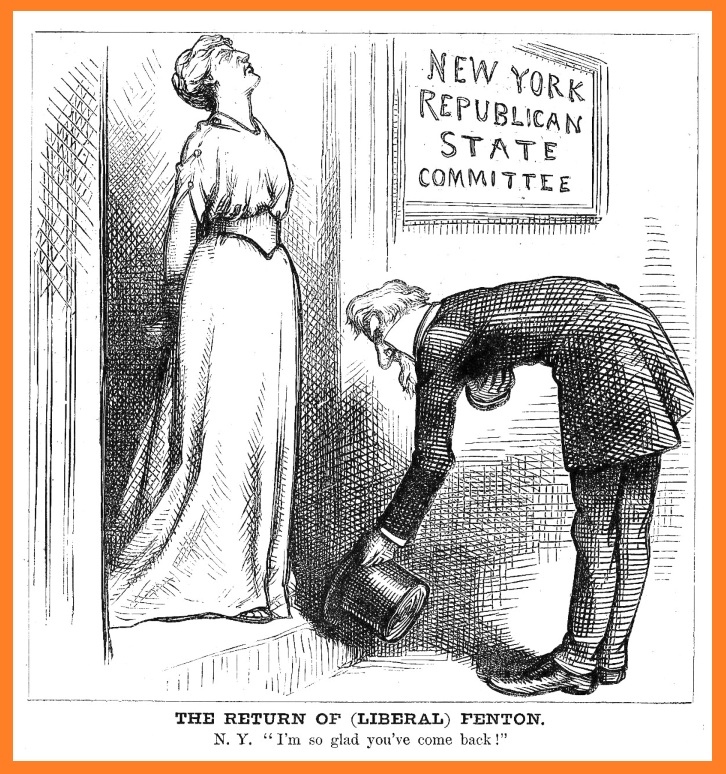

By 1869 Fenton’s political career encountered increasing headwinds. Stymied in his attempt to secure the Republican vice-presidential nomination in 1868 (which went to Schuyler Colfax instead), Fenton secured his election as Senator of New York to serve alongside his rival, Roscoe Conkling. In the political argot of the time, Conkling was a preeminent “Stalwart” Republican, while Fenton belonged to the “Half Breed” camp, the difference between the two centering on their relative enthusiasm for job patronage. The Half Breeds represented that faction within the party that was appalled at the growing corruption within Grant’s administration. Indeed, Fenton’s and Conkling’s relationship deteriorated over the question of who would get the post of Collector of the Port of New York, the most important patronage position in national politics. Fenton and Conklin each backed different candidates. President Ulysses S. Grant’s choice of Conklin’s favorite in 1870 marked the decline of Fenton’s influence both with Grant and with the state party. Fenton widened this split by bolting from the party two years later to throw his lot with the Liberal Republicans and their ill-starred Presidential candidate Horace Greeley. Afterwards, Fenton mended the rift with his party enough to be accepted back into the fold (see the Thomas Nast cartoon, below), but his political career was effectively over. With the Democrats regaining control over New York government, Fenton left the Senate after one term in 1875.

This cartoon by Thomas Nast mocks a contrite Fenton bowing before a disdainful figure representing New York's Republican Party, in an attempt to make amends after he had broken away to support the newspaper editor Horace Greeley in the presidential election of 1872. Greeley's Liberal Republican movement was an alliance between Democrats and disaffected Republicans who disliked the Grant Administration's corruption and its Reconstruction policies (Image source: Harper's Weekly, October 30, 1872).

The International Monetary Conference of 1878

Reuben Fenton’s last stint of public service also earned him a tiny footnote in American monetary history. In 1878, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Fenton to be chairman of the American delegation to the International Monetary Conference convening in Paris that August. Fenton was an inauspicious choice to play the role in such an unpromising cause. Billed as an effort to enhance the status and use of silver in international monetary relations, the conference was an American initiative authorized by the Bland-Allison Act of 1878, a pro-silver measure passed over President Hayes’s veto which committed the U.S. Treasury to purchase bullion and coin quantities of silver dollars according to a monthly schedule. Hayes picked Fenton for the position as a reward for having worked on behalf of his election.

There was little in Fenton’s background that suited him to this task. For Republicans of this time, Fenton’s views on money and banking were thoroughly conventional. As a Representative, Fenton had spoken in favor of the new national banking system. Later, as Governor Fenton supported legislation that encouraged state banks to convert to national charters. Once in the Senate, he proved to be a firm supporter of the gold standard and voted for the Resumption Act of 1875 which put the paper dollar on a path towards gold convertibility. Indeed, at first the Senate refused to confirm his appointment by Hayes, relenting only when Roscoe Conkling, of all people, intervened to push it through, apparently fearing that Hayes might instead name Fenton to the same Collectorship post over which Conkling and Fenton had earlier fought!

With Fenton installed as chairman, the American delegation to the Paris conference was made up of three other people: William S. Groesbeck, an Ohio Congressman; Francis A. Walker, the prominent political economist at Yale (and later MIT); and Samuel Dana Horton, another Ohioan who wrote extensively about silver in the monetary system. Walker and Horton represented the delegation’s intellectual firepower. Both were advocates of bimetallism, or the backing of the U.S. dollar with both silver and gold at a fixed ratio. After being preoccupied with the status of Civil War-era greenbacks, American politics was by then heating up over the monetary role of silver, especially as mounting production from American mines was sending the price of the metal into a twenty-five year decline. Having suspended the free coinage of silver dollars in 1873, Congress began responding to the appeals of agrarian inflationists (for whom restoring bimetallism would expand the money supply) and to the interests of silver mining states (which wanted markets for their output).

In Europe, these concerns found little official resonance. All European governments at the conference were committed to the gold standard and sympathized with the conference agenda only to the extent that doing anything for silver wouldn’t jeopardize their commitment to gold. In particular, Great Britain took part in the proceedings only upon that understanding; its concern with silver related only to exchange relations with India. France and the other countries of the Latin Monetary Union, founded in 1865, were officially committed to bimetallism but in practice had suspended the free coinage of silver, fearing that the falling price of the metal would simply embolden speculators to arbitrage away the gold portion of their monetary circulations. Germany, which had declined to participate in the conference, sat on a large supply of silver left over from its conversion to the gold standard in 1871-73; any support given to the price of silver might only encourage the Germans to dispose of this overhang to the other countries’ detriment.

For these reasons the Europeans were skeptical about the premise of the conference. Moreover, they gently pointed out that it was the Americans themselves who had created their own problem by suspending silver dollar coinage in 1873 and flooding the world with the output of American silver mines. Compounding the embarrassment, it was noted that Reuben Fenton, of all people, had served on the Senate Finance Committee that approved this legislation. In the Europeans’ view, American lawmakers could hardly have not understood what they were doing back in 1873; and, having done what they did, they were now asking the rest of the world to fix their own mess. Lacking any authority to make binding agreements on behalf of their governments, the 1878 conference petered out inconclusively, the delegates accomplishing little beyond agreeing that, yes, something should be done for silver.

Reuben Fenton, Private Citizen and Banker

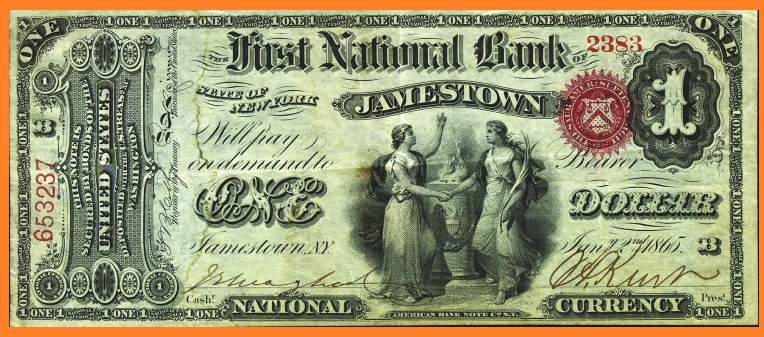

After his exit from politics, Fenton returned to Chautauqua County and lived a celebrity retirement in Jamestown. He participated generously in local civic life and renewed his involvement with the First National Bank of Jamestown. Founded as the Jamestown Bank in 1853, Fenton had served on its board of directors from the very beginning but had little to do with its affairs during his political career. The bank’s first President, Alonzo Kent, and Cashier, Jonathan E. Mayhew, continued in those positions after the adoption of a national charter in 1864 (no. 548). Kent stepped down in 1881 and Fenton was elected President in his place. While the bank clearly benefited from the prestige of his career, by all accounts Fenton took his new vocation seriously and was an active participant in the bank’s daily affairs.

A $1 First Charter note on the First National Bank of Jamestown, New York, signed by Jonathan Mayhew, Cashier, and Alonzo Kent, President (Image source: Heritage Auctions).

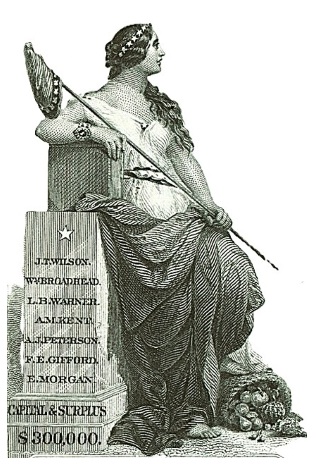

One feature of the certificate of deposit pictured above is a list of names carved on the pedestal against which the figure of Liberty is leaning, grasping her staff topped by a Phrygian cap. This list comprised the bank officers and directors around the turn of the century when this certificate was in use. By that time, Frank E. Gifford was President of the bank and Edward Morgan its Cashier; four others on the list—John T. Wilson (milling and lumber business), Lucius B. Warner (also a lumberman), A. John Peterson (grocer and dry goods merchant), and Alba M. Kent (officer of the Jamestown Worsted Mill and a nephew of Alonzo Kent)—were all directors of the bank. Finally, William Broadhead, the bank’s Vice President, was a textile manufacture and the founder of Jamestown Worsted Mills. He was probably the most prominent personage on the list.

One feature of the certificate of deposit pictured above is a list of names carved on the pedestal against which the figure of Liberty is leaning, grasping her staff topped by a Phrygian cap. This list comprised the bank officers and directors around the turn of the century when this certificate was in use. By that time, Frank E. Gifford was President of the bank and Edward Morgan its Cashier; four others on the list—John T. Wilson (milling and lumber business), Lucius B. Warner (also a lumberman), A. John Peterson (grocer and dry goods merchant), and Alba M. Kent (officer of the Jamestown Worsted Mill and a nephew of Alonzo Kent)—were all directors of the bank. Finally, William Broadhead, the bank’s Vice President, was a textile manufacture and the founder of Jamestown Worsted Mills. He was probably the most prominent personage on the list.

In January 1885, Mayhew, the bank’s first and only cashier up until then, passed away after just over thirty years at his post. Later in August, Fenton was on the bank’s premises one afternoon when he engaged in some jocular banter with his colleagues about the prospects of his own mortality. Later that day, the Cashier Edward Morgan, Mayhew’s successor, returned to Fenton’s office on some errand only to find him dead in his chair from a heart attack.

While he played by the transactional rules of the politics of his time, Reuben Eaton Fenton’s career was a cut above the prevailing political morality. Taken by themselves, his youthful embrace of the Republican Party and his solicitude for veterans could be chalked up to opportunism and voter ingratiation. However, when paired with his willingness later to break with his party in 1872 over the issue of good governance, the arc of his career did seem to be guided by some kind of ethical compass. At the very least, Fenton was never an unabashed apologist for the spoils system in the way that his rival Roscoe Conkling was. President Lincoln's re-election prospects grew less parlous as Union military victories in late 1864 bolstered his public support. Nonetheless, Fenton's gubernatorial campaign that same year probably did some good in carrying the state for Lincoln during an election whose outcome had major implications for the conduct of the war.

.....

REFERENCES

Dow, Charles M., A Century of Commerce and Finance in Chautauqua County, New York (Jamestown, NY, 1905).

McMahon, Helen Grace, “Reuben Eaton Fenton” M.A. Thesis (Cornell University, 1939), quote about Fenton's speaking skills p. 124.

Russell, Henry B., International Monetary Conferences (New York and London: Harper & Brothers, 1898), ch. 5.

A Sketch of the Life of Reuben E. Fenton (New York: George F. Nesbitt & Co., 1866).