Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

$1 Series of 1899 S.C. Series Date Placement Varieties

The Genesis of Postage Currency

Treasury Sealing Assigned to Treasurer’s Office

$100 Counterfeit FRNs

Depositaries at the Port of Wilmington, NC

Large Size Type Signature Changeover Protocols

N.C. Civil War Treasury Notes at Univ. North Carolina

Sand, Clay, Coal and National Banks

Uncoupled

Auction Nights

Quartermaster Colum

Small Notes

Obsolete Corner

Cherry Pickers Corner

Chump Change

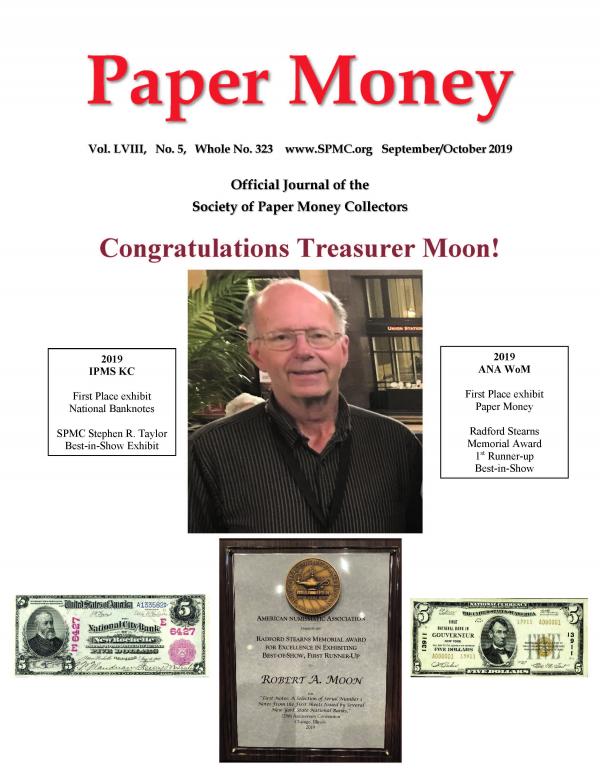

Paper Money

Vol. LVIII, No. 5, Whole No. 323 www.SPMC.org September/October 2019

Official Journal of the

Society of Paper Money Collectors

Congratulations Treasurer Moon!

2019

ANA WoM

First Place exhibit

Paper Money

Radford Stearns

Memorial Award

1st Runner-up

Best-in-Show

2019

IPMS KC

First Place exhibit

National Banknotes

SPMC Stephen R. Taylor

Best-in-Show Exhibit

Now Accepting Consignments to the

Stack’s Bowers Galleries

Official Auctions of the Whitman Baltimore Expos

Call one of our currency consignment specialists to discuss opportunities for upcoming auctions.

They will be happy to assist you every step of the way.

800.458.4646 West Coast Office • 800.566.2580 East Coast Office

Stack’s Bowers Galleries continues to realize strong prices for currency as illustrated by results from

our recent auctions showcased below. When the time comes for you to sell, let us put our world renown

expertise to work for you. Whether you have an entire cabinet or just a few duplicates, the experts at

Stack’s Bowers are just a phone call away and ready to assist you in realizing top dollar for your currency.

Stack’s Bowers Galleries is currently accepting consignments for our full array of live auctions and internet

auctions throughout the year, including the Official Auctions of the Whitman Coin & Collectibles Expos

in Baltimore. Share in our success by putting us to work for you! It may be the most financially rewarding

decision you have ever made.

The Whitman Coin and Collectibles

Winter Expo

Baltimore, Maryland

Auction: November 12-15, 2019

Consignment Deadline: September 18, 2019

The Whitman Coin and Collectibles

Spring Expo

Baltimore, Maryland

Auction: March 18-20, 2020

Consignment Deadline: January 22, 2020

1231 E. Dyer Road, Suite 100, Santa Ana, CA 92705 • 949.253.0916

123 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10019 • 212.582.2580

Info@StacksBowers.com • StacksBowers.com

California • New York • New Hampshire • Hong Kong • Paris

SBG PM Cons2020 PR 190731 America’s Oldest and Most Accomplished Rare Coin Auctioneer

Legendary Collections • Legendary Results • A Legendary Auction Firm

Realized $1,440,000

Fr. 184. 1869 $500 Legal Tender Note.

PCGS Currency Choice About New 55 PPQ.

From the Joel R. Anderson Collection.

Realized $470,000

Fr. 1203. 1882 $100 Gold Certificate.

PCGS Fine 15.

Realized $881,250

Fr. 186c. 1863 $1,000 Legal Tender.

PCGS Fine 15 Apparent.

Realized $372,000

Fr. 2. 1861 $5 Demand Note. Philadelphia. No.17369.

Series 7, Plate A. PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

From the A.J. Vanderbilt Collection.

Realized $660,000

Fr. 376. 1891 $50 Treasury Note.

PCGS Currency Gem New 65 PPQ.

From the Joel R. Anderson Collection.

Realized $1,020,000

Fr. 202a. 1861 $50 Interest

Bearing Note. PCGS Currency Very Fine 25.

From the Joel R. Anderson Collection.

Terms and Conditions

PAPER MONEY (USPS 00-3162) is published every

other month beginning in January by the Society of

Paper Money Collectors (SPMC), 711 Signal Mt. Rd

#197, Chattanooga, TN 37405. Periodical postage is

paid at Hanover, PA. Postmaster send address

changes to Secretary Jeff Brueggeman, 711 Signal

Mtn. Rd, #197, Chattanooga,TN 37405.

©Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc. 2014. All

rights reserved. Reproduction of any article in whole or

part without written approval is prohibited.

Individual copies of this issue of PAPER MONEY are

available from the secretary for $8 postpaid. Send

changes of address, inquiries concerning non - delivery

and requests for additional copies of this issue to the

secretary.

PAPER MONEY

Official Bimonthly Publication of

The Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc.

Vol.LVIII, No. 5 WholeNo. 323 September/October 2019

ISSN 0031-1162

MANUSCRIPTS

Manuscripts not under consideration elsewhere and

publications for review should be sent to the Editor.

Accepted manuscripts will be published as soon as

possible, however publication in a specific issue cannot

be guaranteed. Include an SASE if acknowledgement is

desired. Opinions expressed by authors do not

necessarily reflect those of the SPMC. Manuscripts

should be submitted in WORD format via email

(smcbb@sbcglobal.net) or by sending memory stick/disk

to the editor. Scans should be grayscale or color

JPEGs at 300 dpi. Color illustrations may be changed

to grayscale at the discretion of the editor. Do not

send items of value. Manuscripts are submitted with

copyright release of the author to the Editor for

duplication and printing as needed.

ADVERTISING

All advertising on space available basis.

Copy/correspondence is to be sent to editor.

All advertising is payable in advance.

All ads are accepted on a “good faith” basis.

Terms are “Until Forbid.”

Ads are Run of Press (ROP) unless accepted

on a premium contract basis.

Limited premium space/rates available.

To keep rates to a minimum, all advertising must be

prepaid according to the schedule below. In

exceptional cases where special artwork or additional

production is required, the advertiser will be notified and

billed accordingly. Rates are not commissionable; proofs

are not supplied. SPMC does not endorse any

company, dealer or auction house.

Advertising Deadline: Subject to space availability,

copy must be received by the editor no later than the

first day of the month preceding the cover date of the

issue (i.e. Feb. 1 for the March/April issue). Camera

ready art or electronic ads in pdf format are required.

ADVERTISING RATES

Space 1 Time 3 Times 6 Times

Full color covers $1500 $2600 $4900

B&W covers 500 1400 2500

Full page color 500 1500 3000

Full page B&W 360 1000 1800

Half-page B&W 180 500 900

Quarter-page B&W 90 250 450

Eighth page B&W 45 125 225

Required file submission format is composite PDF

v1.3 (Acrobat 4.0 compatible). If possible, submitted

files should conform to ISO 15930-1: 2001 PDF/X-1a

file format standard. Non-standard, application, or

native file formats are not acceptable. Page size: must

conform to specified publication trim size. Page bleed:

must extend minimum 1/8” beyond trim for page

head, foot, front. Safety margin: type and other non-

bleed content must clear trim by minimum 1/2”

Advertising copy shall be restricted to paper currency,

allied numismatic material, publications and related

accessories. The SPMC does not guarantee

advertisements, but accepts copy in good faith,

reserving the right to reject objectionable o r

inappropriate material or edit copy.

The SPMC assumes no financial responsibility for

typographical errors in ads, but agrees to reprint that

portion of an ad in which a typographical error occurs

upon prompt notification.

Benny Bolin, Editor

Editor Email—smcbb@sbcglobal.net

Visit the SPMC website—www.SPMC.org

$1 Series of 1899 S.C. Series Date Placement Varieties

Peter Huntoon ............................................................... 307

The Genesis of Postage Currency

Rick Melamed. .............................................................. 316

New Members ...................................................................... 327

Treasury Sealing Assigned to Treasurer’s Office

Peter Huntoon ............................................................. 328

$100 Counterfeit FRNs

Bob Ayers ....................................................................338

Depositaries at the Port of Wilmington, NC

Enrico Aidala ............................................................... 343

Large Size Type Signature Changeover Protocols

Peter Huntoon ............................................................. 349

N.C. Civil War Treasury Notes at Univ. North Carolina

Bob Schreiner, et.al. ................................................... 356

Sand, Clay, Coal and National Banks

Jerry Dzara ................................................................. 368

Uncoupled ............................................................................ 370

Auction Nights Loren Gatch ................................................ 374

Quartermaster Colum .......................................................... 376

Small Notes .......................................................................... 378

Obsolete Corner .................................................................. 379

Cherry Pickers Corner............................................................ 382

Chump Change .................................................................... 384

President/Editor ................................................................... 385

Money Mart .......................................................................... 387

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

305

Society of Paper Money Collectors

Officers and Appointees

ELECTED OFFICERS:

PRESIDENT--Shawn Hewitt, P.O. Box 580731,

Minneapolis, MN 55458-0731

VICE-PRESIDENT--Robert Vandevender II, P.O. Box 2233,

Palm City, FL 34991

SECRETARY--Jeff Brueggeman, 711 Signal Mtn., Rd. #197,

Chattanooga, TN 37405

TREASURER --Bob Moon, 104 Chipping Court,

Greenwood, SC 29649

BOARD OF GOVERNORS:

Mark Anderson, 115 Congress St., Brooklyn, NY 11201

Robert Calderman, Box 7055 Gainesville, GA 30504

Gary J. Dobbins, 10308 Vistadale Dr., Dallas, TX 75238

Matt Drais, Box 25, Athens, NY 12015

Pierre Fricke, Box 1094, Sudbury, MA 01776

Loren Gatch 2701 Walnut St., Norman, OK 73072

Joshua T. Herbstman, Box 351759, Palm Coast, FL 32135

Steve Jennings, 214 W. Main, Freeport, IL 61023

J. Fred Maples, 7517 Oyster Bay Way, Montgomery Village,

MD 20886

Wendell A. Wolka, P.O. Box 5439, Sun City Ctr., FL 33571

APPOINTEES:

PUBLISHER-EDITOR--Benny Bolin, 5510 Springhill Estates Dr.

Allen, TX 75002

EDITOR EMERITUS--Fred Reed, III

ADVERTISING MANAGER--Wendell A. Wolka, Box 5439

Sun City Center, FL 33571

LEGAL COUNSEL--Robert J. Galiette, 3 Teal Ln., Essex, CT 06426

LIBRARIAN--Jeff Brueggeman, 711 Signal Mountain Rd. # 197,

Chattanooga, TN 37405

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR--Frank Clark, P.O. Box 117060,

Carrollton, TX, 75011-7060

IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT--Pierre Fricke

WISMER BOOK PROJECT COORDINATOR--Pierre Fricke,

Box 1094, Sudbury, MA 01776

The Society of Paper Money Collectors was organized in 1961 and

incorporated in 1964 as a non-profit organization under

the laws of the District of Columbia. It is affiliated

with the ANA. The Annual Meeting of the SPMC i s

held in June at the

International Paper Money Show.

Information about the SPMC,

including the by-laws and

activities can be found at our website, www.spmc.org. .The SPMC

does not does not endorse any dealer, company or auction house.

MEMBERSHIP—REGULAR and LIFE. Applicants must be at

least 18 years of age and of good moral character. Members of the

ANA or other recognized numismatic societies are eligible for

membership. Other applicants should be sponsored by an SPMC

member or provide suitable references.

MEMBERSHIP—JUNIOR. Applicants for Junior membership must

be from 12 to 17 years of age and of good moral character. Their

application must be signed by a parent or guardian.

Junior membership numbers will be preceded by the letter “j” which

will be removed upon notification to the secretary that the member

has reached 18 years of age. Junior members are not eligible to hold

office or vote.

DUES—Annual dues are $39. Dues for members in Canada and

Mexico are $45. Dues for members in all other countries are $60.

Life membership—payable in installments within one year is $800

for U.S.; $900 for Canada and Mexico and $1000 for all other

countries. The Society no longer issues annual membership cards,

but paid up members may request one from the membership director

with an SASE.

Memberships for all members who joined the Society prior

to January 2010 are on a calendar year basis with renewals due each

December. Memberships for those who joined since January 2010

are on an annual basis beginning and ending the month joined. All

renewals are due before the expiration date which can be found on the

label of Paper Money. Renewals may be done via the Society website

www.spmc.org or by check/money order sent to the secretary.

Pierre Fricke—Buying and Selling!

1861‐1869 Large Type, Confederate and Obsolete Money!

P.O. Box 1094, Sudbury, MA 01776 ; pierrefricke@buyvintagemoney.com; www.buyvintagemoney.com

And many more CSA, Union and Obsolete Bank Notes for sale ranging from $10 to five figures

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

306

$1 Series of 1899

Silver Certificate

Series Date Placement Layout Varieties

Introduction and Purpose

Series of 1899 $1 silver certificate production began December 1898 and continued through

January 1925. Almost 3.5 billion were printed from 21,743 face plates and 9,575 back plates assigned to

the design. More of these notes were made than any other large size U. S. type note. Aside from different

Treasury signature combinations and tinkering with the placement and form of the plate serial numbers, the

only other intaglio face plate varieties that occurred on them during all this time involved the positioning

of the right series date.

The purpose of this article is to document the different series date placement varieties and explain

why they came about.

Obviously, a change in the position of a design element such as the series date constitutes a minor

variety. Even so, some of them have been awarded separate Friedberg catalog numbers, which has forced

collectors to pay serious attention to them. Fr 226 and 226a refer to Lyons-Roberts notes where Fr 226

designates those with the series date above the right serial number. In contrast, the series date is below the

right serial number on the Fr 226a notes.

Equally dramatic are the Fr 229 and Fr 229a Vernon-McClung varieties. The series date occurs

below the serial number on the Fr 229 notes, whereas it was rotated sideways and against the right border

on the Fr 229a notes. Fr 229a notes are quite scarce.

The placement of a series date on a note may seem like a decidedly esoteric concern. However,

moving it about was not done on whims. Its changing position was driven by unfolding technical issues

associated with overprinting serial numbers on the notes. Consequently, the essence of this story revolves

around changing machinery. This gives purpose to the varieties thus solidifying their legitimacy.

Serial Numbering Machinery

The Series of 1899 spanned every major means used to number large size currency.

Figure 1. $1 Series of 1899 Lyons-Roberts silver certificate with the right series above the serial

number. The right series moved during the life of the series. It occupied its highest position on

these first notes in the series, which were given catalog number Fr 226.

The Paper

Column

Peter Huntoon

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

307

When the series began, authority for serial numbering and sealing the notes was split between the

Bureau of Engraving and Printing and the U. S. Treasurer’s office. The notes were printed in 4-subject sheet

form and numbered at the Bureau, then sent to the Treasurer’s Division of Issue to be sealed and separated.

The serial numbers were applied to the sheets at the BEP by women who operated paging

machines. A paging machine held a single numbering head that was used to stamp the serial numbers onto

the sheet one serial number at a time. Each sheet required eight applications. The $1 1899 notes were

designed such that the right series date served as a guide to help the operator position the numbering head

in order to apply that number.

Rotary serial numbering presses made by the Potter Printing Press Company came on line in 1903

that revolutionized the process. The presses applied all eight numbers as the sheet passed through the press.

The sealing and separating operations were still carried out at the U. S. Treasurer’s office.

Several years later a radically new machine was designed at the Bureau and built by the Harris

Automated Press Company that both numbered and sealed 4-suject sheets, and also separated the notes and

collated them in numerical order. The Secretary of the Treasury authorized the transfer of the sealing

operation to the Bureau from the Treasurer’s Division of Issue and the Harris machines came on-line in

1910. From then on, the Bureau delivered currency to the Treasurer’s office in note rather than sheet form.

Lyons-Roberts Move

The positon of the right series date is specified by the vertical distance in millimeters between the

base of the I in “America” and the base of “Series of 1899.”

The right series date occupied a high position on the first 100,000,000 $1 Series of 1899 notes;

specifically, at 4 mm. It was abruptly dropped to 9.5 mm in June 1901. See Figure 3.

The 4 mm Fr 226 notes comprise the first serial number block in the series and they have no prefix

letter. See Figure 1. Serial numbering of the 9.5 mm Fr 226a Lyons-Roberts notes commenced at A1.

I have not documented the technical explanation for the move, but suspect it was made to aid the

paging machine operators. When the series date was in the 4-mm position, it was hidden behind the

numbering head on the machine as the operators looked down on the sheets whereas at 9.5 mm it was in

front in plain view. Consequently, at 9.5 mm it could better serve as a guide for the placement of the right

serial number and reduce spoilage caused by accidentally printing the serial number on it.

The changeover from the use of plates with 4 mm spacing to 9.5 mm on the printing presses was

abrupt on June 28, 1901. The production from the two varieties was necessarily segregated for numbering.

Figure 2. Sealing

currency at the

Division of Issue

in U. S. Treasury

Building after the

numbered sheets

had been

delivered from the

Bureau of

Engraving and

Printing. Sealing

was carried out at

the Division of

Issue from 1885 to

1910. Shown are

flatbed cylinder

typographic

sealing presses.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

308

Table 1. Changeover plate numbers when the right series date on $1 Series of 1899 plates

was lowered from 4 to 9.5 mm in June 1901 during the Lyons- Roberts era.

Treasury Plate No. Plate Serial No. Position Certification Date

12400 507 above May 8, 1901

12405 508 below June 3, 1901

12408 509 above May 8, 1901

12411 510 below June 3, 1901

Vernon-McClung Lowering

Major changes were afoot

during the Vernon-McClung era.

Rotary press numbering of the sheets

had been implemented in 1903.

Consequently, the right series date no

long served as a guide for the placement

of the right serial number. However, an

annoying problem came into play. The

wetting of the paper required for

intaglio printing resulted in differential

shrinkage of the paper. The rotary

numbering presses blindly printed the

serials at set intervals, so occasionally

the right one landed on the right series

date, which caused spoilage.

Figure 3. The right series was moved

from above the right serial number at 4

mm (left) to below at 9.5 mm (right)

during the Lyons-Roberts era. The

distance is measured from the base of

the I in “America” to the base of “Series

of 1899.”

Figure 4. Illustration showing the four

placements of “Series of 1899” on the

right side of Vernon-McClung notes that

began with the 9.5 mm spacing inherited

from the Lyons-Treat era, a small group

at 10.5 mm, followed by a large group at

12 mm. Finally, the series was turned on

end and pushed against the right border.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

309

The solution was to lower the right series date again so that it would be out of the way of the serial

number. This step was untaken during November and December of 1909 and the final outcome was to

lower it to 12 mm. See Figure 4.

The changeover looked messy to Huntoon, Hewitt and Murray (2014) when they looked at the

proofs in the Smithsonian in order to determine the spacing on each. They found that the spacing was mixed

within a group of 100 consecutive Vernon-McClung plates having plate serial numbers between 5579 and

5678. Not only that but five of those plates sported intermediate placements of about 10.5 mm. To further

complicate the situation, a group of ten obsolete but never used Vernon-Treat plates had been altered by

swapping out Vernon’s signature for McClung’s and simultaneously lowering the series date from 9.5 to

12 mm. That work was completed between December 14 and 16, 1909 and those plates arrived as the first

with the 12-mm spacing.

The disarray clarified beautifully when the plates were arranged in order of their certification dates.

The result is presented on Table 2. The certification dates represent the order in which the plates were

finished so they reveal exactly when the decisions were made about where to place the series date.

Initially they decided to lower the series date to 10.5 mm. Then they quickly decided that 12 mm

was better.

Table 2. Well-defined temporal transition from 9.5 to 12 mm spacing of the right series date on $1

Vernon-McClung Series of 1899 silver certificate plates that became evident when the plates were

arranged in order of completion date. Comment column: VT=Vernon-Treat, VM=Vernon-McClung, the Vernon-

Treat versions of the plates had not been used prior to being altered to Vernon-McClung.

Treas. Plate Serial Number

Pl. No 9.5 mm 10.5 mm 12 mm Certification Date Comment

31593 5668 Nov 15, 1909

31607 5670 Nov 15, 1909

31603 5669 Nov 18, 1909

31608 5671. Nov 18, 1909

31622 5673 Nov 18, 1909

31647 5677 Nov 18, 1909

31621 5672 Nov 20. 1909

31623 5674 Nov 22, 1909

31635 5675 Nov 22, 1909

31652 5678 Nov 22, 1909

31636 5676 Nov 24, 1909

30917 5556 Dec 14, 1909 VT 9.5 mm altered to VM 12 mm

31085 5576 Dec 14, 1909 VT 9.5 mm altered to VM 12 mm

30895 5545 Dec 15, 1909 VT 9.5 mm altered to VM 12 mm

31055 5570 Dec 15, 1909 VT 9.5 mm altered to VM 12 mm

31079 5575 Dec 15, 1909 VT 9.5 mm altered to VM 12 mm

31086 5577 Dec 15, 1909 VT 9.5 mm altered to VM 12 mm

30893 5544 Dec 16, 1909 VT 9.5 mm altered to VM 12 mm

30914 5555 Dec 16, 1909 VT 9.5 mm altered to VM 12 mm

31056 5571 Dec 16, 1909 VT 9.5 mm altered to VM 12 mm

31078 5574 Dec 16, 1909 VT 9.5 mm altered to VM 12 mm

31660 5679 Dec 17, 1909

31667 5680 Dec 17, 1909

31668 5681 Dec 17, 1909

31673 5682 Dec 17, 1909

31124 5589 Dec 21, 1909

31092 5579 Dec 23, 1909

The plates being made during this period were 4-subject plates that were used individually on spider

presses. All the serviceable plates regardless of spacing were sent to press concurrently until the last of the

9.5 and 10.5 mm plates wore out. The production from them was intermingled and fed through the Potter

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

310

rotary numbering presses without regard to the spacing. The sheets were then sent to the Treasury for

overprinting of the seals and separation into individual notes.

Problems with right serial numbers landing on the series date on the 9.5 and 10.5 mm notes during

the transition period had to be dealt with by removing the spoiled sheets at the BEP or during the final

inspection of the notes at the Treasury Department. The reality was that interference between the series date

and serial number wasn’t totally resolved, even after introduction of the 12 mm notes.

The high, intermediate and low placement varieties currently are lumped together as Fr 229 notes.

The 10.5 and 12-mm spacings began to appear on notes with serial numbers greater than V10000000.

Probably those with 10.5 mm spacing will prove to be quite scarce.

Changeover pairs between the varieties were made although none have been reported yet.

Vernon-McClung Horizontal to Vertical Move

The right series date was moved from the 12-mm horizontal position to vertical against the right

border in 1911 during production of the Vernon-McClung notes. Bureau of Engraving and Printing Director

Joseph E. Ralph wrote a letter to Secretary of the Treasury Franklin MacVeagh on June 20, 1910, requesting

approval for the change in which he explained how it was to be accomplished. The material in the square

brackets has been added for clarity.

June 20, 1910

The Honorable Secretary of the Treasury

Sir:

In preparing the designs for notes and certificates, the words “Series of –” were placed on the right-

hand side of the note in the position indicated by the model herewith marked A, to give a guide line for the

numbering, which was executed on hand-operated numbering machines [paging machines], but the

location of these words has given considerable trouble since the numbering, as well as the sealing, has been

done on printing presses [Potter numbering machines placed in service in 1903 & Harris numbering and

sealing machines placed in service in 1910], for the reason that the slightest variation in position of either

the number or seal, due to the unequal shrinkage of the paper, causes the printing to cover the inscription.

The original die used for making plates for $1 silver certificates is cracked and it is necessary to harden

and use a duplicate of it, but before hardening the die I desire to take advantage of the opportunity and

change the location of the inscription to the position at the extreme right-hand edge of the note, as shown

by model B herewith.

I have the honor, therefore, to request that the matter be referred to the Treasurer of the United States

for consideration, and that if he approves the change, and you concur therein, such approval be indicated

on the model B, and both models be returned.

It is desired to have this authority apply as well to other denominations of other notes and certificates.

Respectfully

J. E. Ralph

Director

The vertical placement created the popular and scarce Fr 229a Vernon-McClung variety and

subsequently was used for the rest of the signature combinations in the series.

The changeover to the vertical variety was as complicated as the changeover from the 9.5 to 12 mm

spacings because there was simultaneous production of the plates with the 12 mm and vertical varieties

between plate serial numbers 6734 and 6803. However, unlike the 9.5 to 12 mm changeover, this

changeover did not break at a specific certification date. The technical explanation for why is that some

siderographers were provided with rolls made from the new die with the vertical series date whereas others

were using obsolete rolls without it. All of these plates were 4-subject plates used individually on one-plate

spider presses.

There is great interest in the Fr 229a variety so all the plates involved in the changeover are listed

on Table 3. Be aware that in addition to the 43 Fr 229a plates listed on Table 3, another 78 with plate serial

numbers 6803 to 6881 were made to close out the Vernon-McClung issues.

The on-press data on Table 3 reveal that the plates were sent to press as soon as they became

available. The result was concurrent production of the 12 mm and vertical varieties. We know from reported

serial number data (Gengerke, 2014) that they were comingled and fed through the Harris numbering

machines without regard to the position of the right series date. This occurred between serial numbers

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

311

ranging from about Y247---- through Y51------, with a second group of late-numbered notes from about

Y684----- through Y689-----. The late numbered notes are explained in Huntoon (2016).

Table 3. Series of 1899 $1 silver certificate plates with Vernon-McClung signatures that were

made during the 1911 transition period when some plates were completed with the 12-mm

horizontal placement of "Series of 1899" in the upper right quadrant (Fr 229) and others were

completed with the series date oriented vertically against the right border (Fr 229a).

Treas. Plate Cert.

Plate No. Serial No. Date Placement On-Press Dates - inclusive

35226 6734 Mar 28, 1911 vertical-first Mar 29, 1911-Jun 19, 1911

35229 6735 Mar 29, 1911 horizontal Mar 30, 1911 - May 3, 1911

35230 6736 Mar 29, 1911 horizontal Mar 30, 1911 - May 22, 1911

35231 6737 Mar 29, 1911 horizontal Mar 30, 1911 - May 5, 1911

35237 6738 Mar 30, 1911 horizontal May 31, 1911 - Apr 21, 1911

35238 6739 Mar 31, 1911 horizontal Mar 31, 1911 - May 25, 1911

35241 6740 Apr 1, 1911 horizontal Apr 3, 1911 - Jun 12, 1911

35242 6741 Apr 5, 1911 horizontal Apr 6, 1911 - May 23, 1911

35245 6742 Apr 5, 1911 horizontal Apr 9, 1911 - Jun 14, 1911

35246 6743 Apr 3, 1911 horizontal Apr 4, 1911 - Jun 5, 1911

35247 6744 Mar 31, 1911 horizontal Apr 1, 1911 - May 2, 1911

35248 6745 Mar 30, 1911 vertical Mar 31, 1911 - May 16, 1911

35253 6746 Apr 1, 1911 vertical Apr 3, 1911 - Jun 7, 1911

35255 6747 Mar 30, 1911 horizontal Apr 1, 1911 - May 25, 1911

35256 6748 Apr 6, 1911 horizontal Apr 7, 1911 - May 16, 1911

35259 6749 Mar 31, 1911 vertical Apr 3, 1911 - Jun 14, 1911

35262 6750 Apr 3, 1911 horizontal Apr 4, 1911 - May 8, 1911

35263 6751 Apr 4, 1911 horizontal Apr 6, 1911 - Jun 19, 1911

35265 6752 Apr 8, 1911 vertical Apr 10, 1911 - May 26, 1911

35267 6753 Apr 1, 1911 horizontal Apr 3, 1911 - May 15, 1911

35269 6754 May 4, 1911 vertical May 10, 1911 - Aug 2, 1911

35270 6755 Apr 8, 1911 vertical Apr 10, 1911 - Jun 13, 1911

35272 6756 Apr 3, 1911 horizontal May 3, 1911 - May 22, 1911

35273 6757 Apr 20, 1911 vertical Apr 22, 1911 - Jun 13, 1911

35274 6758 Apr 4, 1911 vertical Apr 5, 1911 - Jun 10, 1911

35275 6759 Apr 22, 1911 vertical Apr 26, 1911 - May 16, 1911

35276 6760 Apr 4, 1911 horizontal Apr 6, 1911 - Jun 2, 1911

35278 6761 Apr 5, 1911 vertical Apr 7, 1911 - Jun 1, 1911

35285 6762 Apr 11, 1911 horizontal Apr 12, 1911 - May 16, 1911

35286 6763 Apr 20, 1911 vertical Apr 26, 1911 - May 27, 1911

35288 6764 Apr 20, 1911 vertical Apr 27, 1911 - Jun 1, 1911

35289 6765 Apr 20, 1911 vertical Apr 27, 1911 - May 24, 1911

35290 6766 Apr 10, 1911 horizontal Apr 11, 1911 - Jun 3, 1911

35291 6767 Apr 10, 1911 vertical Apr 11, 1911 - Jun 6, 1911

35296 6768 Apr 8, 1911 vertical Apr 10, 1911 - Jun 13, 1911

35301 6769 Apr 6, 1911 vertical Apr 7, 1911 - Jun 8, 1911

35303 6770 Apr 8, 1911 vertical Apr 10, 1911 - May 10, 1911

35304 6771 Apr 21, 1911 horizontal Apr 25, 1911 - May 31, 1911

35305 6772 Apr 21, 1911 horizontal Apr 25, 1911 - May 29, 1911

35306 6773 Apr 19, 1911 vertical Apr 11, 1911 - May 17, 1911

35311 6774 plate not finished

35312 6775 Apr 20, 1911 horizontal Apr 27, 1911 - Jun 21, 1911

35316 6776 Apr 8, 1911 vertical Apr 10, 1911 - Jun 19, 1911

35318 6777 Apr 12,1911 vertical Apr 14, 1911 - Jun 6, 1911

35320 6778 Apr 14, 1911 horizontal Apr 17, 1911 - May 27, 1911

35321 6779 Apr 11, 1911 vertical Apr 12, 1911 - Jul 18, 1911

35325 6780 Apr 11, 1911 vertical Apr 12, 1911 - Jun, 28, 1911

35327 6781 Apr 12, 1911 vertical Apr 14, 1911-Jun 15, 1911

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

312

35329 6782 Apr 13, 1911 vertical Apr 14, 1911 - Jun 12, 1911

35331 6783 Apr 15, 1911 vertical Apr 17, 1911 - May 18, 1911

35333 6784 Apr 15, 1911 vertical Apr 18, 1911 - Jun 9, 1911

35335 6785 Apr 13, 1911 vertical Apr 14, 1911 - May 23, 1911

35339 6786 Apr 15, 1911 vertical Apr 17, 1911 - May 17, 1911

35340 6787 Apr 19, 1911 vertical Apr 20, 1911 - Jun 7, 1911

35343 6788 Apr 15, 1911 vertical Apr 18, 1911 - Jun 30, 1911

35344 6789 Apr 15, 1911 vertical Apr 18, 1911 - Jun 17, 1911

35347 6790 Apr 15, 1911 vertical Apr 18, 1911 - Jun 24, 1911

35349 6791 Apr 15, 1911 vertical Apr 18, 1911 - May 29, 1911

35352 6792 Apr 27, 1911 vertical Apr 28, 1911 - Jun 16, 1911

35353 6793 Apr 22, 1911 vertical Apr 27, 1911 - May 31, 1911

35354 6794 Apr 18, 1911 vertical Apr 19, 1911 - Jun 24, 1911

35358 6795 Apr 15, 1911 vertical Apr 18, 1911 - May 17, 1911

35359 6796 Apr 21, 1911 vertical May 19, 1911 - Jun 15, 1911

35360 6797 Apr 29, 1911 vertical May 1, 1911 - Jun 29, 1911

35361 6798 Apr 18, 1911 vertical Apr 19, 1911 - Jun 9, 1911

35362 6799 May 2, 1911 horizontal May 4, 1911 - Jun 6, 1911

35363 6800 Apr 15, 1911 vertical Apr 18, 1911 - Jun 7, 1911

35368 6801 Apr 29, 1911 horizontal May 1, 1911 - May 26, 1911

35371 6802 Apr 27, 1911 vertical Apr 28, 1911 - Jun 9, 1911

35373 6803 Apr 27, 1911 horizontal-last Apr 28, 1911 - Jun 17, 1911

Overview

The placement of the right series date was moved over the course of the production of the Series

of 1899 $1 silver certificates. It was first moved from the 4-mm horizontal position downward to 9.5 mm

on the Lyons-Roberts notes in 1901. Next is was moved downward first to 10.5 and then to 12 mm in 1909

during the Vernon-McClung era. Finally, it was reoriented vertically and placed against the right border in

1911 at the end of the Vernon-McClung era.

The purpose of the move during the Lyons-Roberts era was to position the series date below the

right serial number so that the women operating the paging machines could see it and better use it as a guide

for placing the number. During the Vernon-McClung era, the number was moved progressively downward

and finally over to the right border to get it out of the way of the right serial number, because by then the

serial numbers were being printed from rotary numbering presses and some were landing on the series date

owing to differential shrinkage of the paper.

The ability to move the right series date to create the 4, 9.5, 10.5 and 12 mm plates was facilitated

by the fact that the right series date was not on the rolls used to lay-in the generic intaglio designs on the

Figure 5. One of only two reported $1 Series of 1899 Vernon-McClung star notes with the right

series against the right border. Photo courtesy of Doug Murray.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

313

printing plates. Instead it was on separate rolls. It and the Treasury signatures were added after the generic

faces had been laid in.

When a new generic face die was made in 1911, the right series date was incorporated on it against

the right border. Consequently, the rolls made from it carried the date.

Table 4. Inclusive on-press dates for $1 Series of 1899 Silver Certificate plates with the different placements of the

right series date. LR = Lyons-Roberts, VM = Vernon-McClung, SW = Speelman-White.

Range of Plate Range of Treasury

Series date placement Serial Numbers Plate Numbers Inclusive On-Press Dates

horizontal series date above serial LR 1 - LR 509 8618 - 12408 Dec 6, 1898 - Jun 28, 1901

horizontal series date below seal at 9.5 mm LR 508 - VM 5677 12405 - 31647 Jun 28, 1901 - Apr 19, 1910

horizontal series date below seal at 10.5 mm VM 5672 - VM 5678 31621 - 31652 Dec 3, 1909 - Feb 8, 1910

horizontal series date below seal at 12 mm VM 5544 - VM 6803 30893 - 35373 Dec 15, 1910 - Jun 21, 1911

vertical series date at right end VM 6734 - SW 2922 35226 - 95927 Mar 29, 1911 - Jan 8, 1925

The discussion above provides non-star serial number data for the various changes. Star notes were

introduced in 1910 coinciding with the arrival of the Harris numbering, sealing, separating and collating

machines (Huntoon and Lofthus, 2014). This means, of course, that the scarce Vernon-McClung vertical

placement variety also occurs on star notes. Only two are recorded in the Gengerke census; specifically,

*1146220B and *1153709B. See Figure 5.

The star notes offer a lesson. The astute variety collector has the opportunity to acquire significant

rarities by paying attention to the placement of the right series date. It is likely that the 10.5 mm placement

variety from Vernon-McClung plates 5672, 5674, 5675, 5676 and 5678 will prove to be scarce to rare on

both regular and star notes when people start to look for them.

Acknowledgment

This topic was first treated in Huntoon, Hewitt and Murray (2014). This article updates and corrects

that piece and delves further into how the Bureau of Engraving and Printing handled the transitions between

the varieties.

References Cited and Sources of Data

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 1899-1923, Certified proofs of $1 Series of 1899 silver certificates: National Numismatic

Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, various dates, Plate history ledgers: Record Group 318, U. S. National Archives, College Park,

MD.

Gengerke, Martin, 2014, U. S. paper money records, a census of U. S. large size type notes: privately produced on demand by

gengerke@aol.com.

Huntoon, Peter, Nov-Dec 2016, Large size type note signature changeover protocols created collectable varieties: Paper Money, v.

55, p. 414-423.

Huntoon, Peter, Shawn Hewitt and Doug Murray, Mar-Apr 2014, Series date placement varieties on the right side of $1 Series of

1899 silver certificates: Paper Money, v. 53, p. 84-97.

Huntoon, Peter, and Lee Lofthus, Nov-Dec 2014, The birth of star notes, the back story: Paper Money, v. 53, p. 400-411.

Ralph, Joseph E, Director of Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Jun 20, 1910, Letter to Secretary of the Treasury Franklin

MacVeagh concerning the placement of the right series date on $1 Series of 1899 silver certificates: Bureau of Engraving

and Printing, miscellaneous and official letters sent, vol. 376, p. 439: Record Group 318 (318/450/79/8/v. 284), U. S.

National Archives, College Park, MD.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

314

Lyn Knight Currency Auct ions

If you are buying notes...

You’ll find a spectacular selection of rare and unusual currency offered for

sale in each and every auction presented by Lyn Knight Currency

Auctions. Our auctions are conducted throughout the year on a quarterly

basis and each auction is supported by a beautiful “grand format” catalog,

featuring lavish descriptions and high quality photography of the lots.

Annual Catalog Subscription (4 catalogs) $50

Call today to order your subscription!

800-243-5211

If you are selling notes...

Lyn Knight Currency Auctions has handled virtually every great United

States currency rarity. We can sell all of your notes! Colonial Currency...

Obsolete Currency... Fractional Currency... Encased Postage... Confederate

Currency... United States Large and Small Size Currency... National Bank

Notes... Error Notes... Military Payment Certificates (MPC)... as well as

Canadian Bank Notes and scarce Foreign Bank Notes. We offer:

Great Commission Rates

Cash Advances

Expert Cataloging

Beautiful Catalogs

Call or send your notes today!

If your collection warrants, we will be happy to travel to your

location and review your notes.

800-243-5211

Mail notes to:

Lyn Knight Currency Auctions

P.O. Box 7364, Overland Park, KS 66207-0364

We strongly recommend that you send your material via USPS Registered Mail insured for its

full value. Prior to mailing material, please make a complete listing, including photocopies of

the note(s), for your records. We will acknowledge receipt of your material upon its arrival.

If you have a question about currency, call Lyn Knight.

He looks forward to assisting you.

800-243-5211 - 913-338-3779 - Fax 913-338-4754

Email: lyn@lynknight.com - support@lynknight.c om

Whether you’re buying or selling, visit our website: www.lynknight.com

Fr. 379a $1,000 1890 T.N.

Grand Watermelon

Sold for

$1,092,500

Fr. 183c $500 1863 L.T.

Sold for

$621,000

Fr. 328 $50 1880 S.C.

Sold for

$287,500

Lyn Knight

Currency Auctions

Deal with the

Leading Auction

Company in United

States Currency

THE GENESIS OF POSTAGE CURRENCY

By Rick Melamed

ECONOMIC CAUSE AND RESULTING NEED FOR COIN ALTERNATIVES

It is a well-established fact that it was the severe coin shortages in the early 1860’s that gave rise to the

creation and issuance of postage currency. The reasons behind the shortages are complicated by many contributing

factors. The seeds were planted with the financial panic of 1857 which arose from an over-extension of

commercial loans and their subsequent, wide-spread defaults. Much of this is attributed to the slowdown of mined

gold and the collapse of the overleveraged railroad industry who were betting heavily on their continued expansion

out west. As gold supplies slowed to a trickle, payment on the loans used for expansion by the railroad and related

industries could not be met. It resulted in wide spread bank closings and many businesses going bankrupt. In

turn, this made borrowing money by the Federal Government more difficult. At the time of poor economic

conditions the Government needed more money to meet the expenses of running the country and funding the Civil

War.

Certainly the breakout of the Civil War was a factor, but circumstances involving the Treasury and U.S. banks

added to the coin shortage problem. It was not a harmonious relationship. In late August 1861, Treasury Secretary

Salmon Chase created circulating U.S. currency, Demand Notes. Commercial banks at the time opposed their

issuance since it would compete with their own manufactured “Bank Notes.” Secretary Chase insisted that the

banks accept the Demand notes and they were eventually and reluctantly accepted in deposit. In December 1861

the ability of the U.S Government to redeem Demand Notes in specie (specie is money in the form of coins and

not currency) came under great pressure. Chase indicated that war expenditures were far exceeding Federal

revenue expectations. By the end of December 1861, banks suspended specie payments on their own “bank notes.”

In turn, Demand Notes turned up in great numbers at the Treasury for redemption. With all the demand for specie,

the government could not obtain adequate supplies of coins to fulfill their obligations. Eventually the Government

was forced to follow suit and suspend the redemption of Demand Notes for gold in the first few days of 1862. By

suspending specie payment, the holder would not be able to redeem their notes in coins. The unfortunate effect not

only made gold and silver coins virtually disappear from circulation, it also had the deleterious effect of paper

money losing value relative to what it could fetch in precious metal coins. By June 1862, paper currency was worth

only about 91% of its value to precious metals. Citizens’ reactions were either to horde coins or trade them to

brokers for a premium; and in turn the brokers were exporting much of the silver and gold out of the country. The

net result was a severe coin shortage. At its nadir, there were literally no circulating coins to be found. Coin

production during the postage/fractional currency period (1862-1876) dropped precipitously. For example: in 1857

the Treasury minted 9.6 million quarters; in 1868 only 30,000 were made. 8.6 million half dimes were produced

in 1857; from 1862-1867 about 130,000 were made per year.

This proved to be an existential crisis and a solution needed to be found quickly. A paralyzed nation was

desperate for answers.

INTERIM SOLUTION #1 – CIVIL WAR TOKENS AND PRIVATE SCRIP

Many private firms resorted to minting their own tokens as a means to counteract the coin shortages. Civil

War Tokens or CWT’s (also colloquially knowns as “Hard Time Tokens”), were a short term solution albeit with

less than 100% acceptance. Generally their value was 1¢ or 2¢; though there are examples valued up to 50¢. They

were categorized in 3 main areas: merchant tokens, patriotic tokens and Sutler tokens (used by private merchants

when dealing with the Army or Navy). Often the obverses had images of period coinage such as Indian head cents;

historical or allegorical figures were also used. Many included patriotic sentiments reacting to the Civil War. The

reverses would often contain the name of a merchant.

CWT’s were in existence from 1861-64. But by June 1864 the U.S. Government made them illegal for use

realizing that privately issued coinage was a very bad idea.

CWTs are avidly collected today and have a large collector base. They are an interesting artifact, their

existence borne out of desperate times.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

316

The amount of privately issued merchant scrip is vast. Like CWTs they lacked anything of fungible value.

Their worth was only as good as the issuing merchants’ word to take them in trade. So literally their worth is

the paper they were printed on. Books have been written on the subject and we endeavor to bypass this with only

the mention of their use during their period of issue.

INTERIM SOLUTION #2: ENCASED POSTAGE

John Gault was a savvy businessman and saw two ways

that he could profit off the implementation of these new “coins.”

First, Gault sold his encased postage to businesses that had a

high demand for coins. He charged 20% of the face value of the

stamp to defray his manufacturing costs.

Secondly, he soon realized that the blank brass backing

provided space that could be used for advertising. Companies

paid Gault a 2¢ premium on top of the cost of the stamp in

exchange for a customized case to the specifications of the

company’s advertising desires. At least 30 companies stamped

advertisements on the backing of his brass currency. Gault sold

an estimated $50,000 in encased postage stamps. Of the

approximately 750,000 pieces sold, only 3,500-7,000 are

believed to have survived.

Gault’s encased postage was only a momentary success (from

1862-63).

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

317

INTERIM SOLUTION #3: POSTAGE STAMPS HASTILY PRESSED INTO USE

With virtually no coins in circulation, businesses resorted to using anything they could find as a replacement.

Tickets, private scrip, coupons, IOUs to name a few; but on a much larger scale postage stamps, because their

value was backed by the government, were rushed into use to make change for commercial transactions. Matt

Rothert from his 1963 book, A Guide Book of United States Fractional Currency, gives a very good explanation

on how postage stamps were put into use as “postage” coins.

Because of the severe shortage of circulating coins, the country was really hard pressed to carry on even the

simplest commercial activities in early 1862. On July 14th of that year, Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P Chase

suggested two alternative proposals to Congress. The first outlined a plan for the reduction in size of silver coins

and for the second; Chase asked for the authority to issue and use ordinary postage stamps as circulating change.

Chase himself favored the proposal that would legalize the circulation of small squares of gummed paper (postage

stamps) on a national medium of exchange. Congress went ahead and adopted the postage stamp idea, and it

became law when President Lincoln signed the bill on July 17, 1862. The immediate effect of the law was a

run on stamps at the post offices as they were needed everywhere a n d no means had been provided by The

Treasury Department to acquire and release the stamps as money.

The volume of stamps purchases increased dramatically. In New York, for example, stamp sales jumped from

a daily amount of $3,000 to over $20,000 soon after the new law was announced. The supply of stamps soon was

exhausted. Postmaster General Montgomery Blair was understandably irritated, since he had not been consulted

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

318

beforehand. He therefore refused to permit further sale of stamps to be used as money. The Treasury Department

then called the Commissioner of Internal Revenue, George Boutwell, to settle things with Blair. In short, Boutwell

suggested that specially marked stamps be made; that the Treasury sell and redeem them, that post offices accept

them as postage, and that either party be free to withdraw from such an agreement. Blair accepted these proposals

and went ahead to print the special stamps for the treasury.

Shown are the stamps used to combat the coin shortage

crisis. These are familiar to paper money collectors since

their image was used on postage currency (more on that

later in this article). Since the U.S. Post Office is a federal

agency it was reasoned that postage stamps could be

pressed into service as change. This solution became

temporary due to the fragile nature of a thin, paper postage

stamp. Postage stamps were easily torn and damaged by

constant handling. The adhesive backs literally gummed up

the works and even when the Postal Service had the

National Bank Note Company print un-gummed stamps it

did not alleviate their fragility. Additionally, there was

concern that cancelled stamps used as postage could have the ink removed

and be re-used as postage coins.

INTERIM SOLUTION #4: POSTAGE ENVELOPES & PRIVATE SCRIP UTILIZING POSTAGE

STAMPS

There were merchants who realized that the value of federally issued postage stamps created a tangible and

transferrable asset. The inherent problem of using stamps as a replacement for circulating coins was obvious.

Postage stamps were a one-time use item whereas coins were meant for constant circulation. To alleviate the

inconvenience of raw stamps, many merchants created postage envelopes with their value printed on the face.

Inserting stamps inside the envelope was a more efficient way to make change for commercial transactions. It

protected the stamps from constant human exposure and it was a convenient piece of advertising. Postage

envelopes widely circulated in the 1860’s and are avidly collected today; an interesting ephemeral artifact borne

out of desperate times.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

319

Several enterprising merchants came up with a better idea of pasting stamps onto pre-printed pieces of

rectangular paper. In the process private scrip was created with the intrinsic value of the affixed stamps being its

net worth. The recipient would not have to look inside the envelope to see if the amount of stamps equaled the

preprinted value of the envelope. With a quick glance the value of the stamps could be easily equated to the

preprinted value of the scrip. The following bit of ingenuity from Stack’s sale of the John Ford collection is by a

Newport grocer, William Newton & Co. The July 4, 1862, date was a month before U.S. issued postage currency

came into existence. It must’ve surely influenced U.S. Treasurer Francis Spinner in his initial design of postage

currency proofs.

LONG TERM SOLUTION: U.S. TREASURER FRANCIS SPINNER TO THE RESCUE: HOW

POSTAGE CURRENCY WAS DEVELOPED

Private scrip, postage envelopes, encased postage and CWTs were never produced in the quantities that could

support an entire nation’s need for circulating coinage.

American citizens and businesses were already stung by the suspension of specie and federally issued

Demand notes worth less than par in gold and silver. Exacerbated by worthless bank issued currency and private

firms issuing their own coins, scrip and currency; it was clear, that the Treasury had to take control and put the

circulating money supply back into government hands. Failure to act would cause continued economic chaos

with a broad economic collapse a near certainty.

Francis Spinner was first to foster the idea of converting postage stamps

into postage currency; usable as a substitute for coins.

Spinner systematically developed the idea that solved the coin

shortage problem. The introduction of postage and fractional currency

into daily use

Drawing from various archives including Spinner’s own personal

collection, currently residing in the Smithsonian, we are able to recreate

some of the processes Spinner undertook from the first crude postage stamp

currency proofs to the finished product: circulating postage currency.

Francis E. Spinner

U.S. Treasurer

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

320

A newspaper article in the Washington Star in 1860’s sums things up succinctly:

In 1862 Small Change became very scarce it was more than a day's search to find a $0.05 silver piece. General

Spinner was then Treasurer of the United States. He was constantly appealing to and from all quarters to do

something to supply the demand for small change. In his dilemma he thought to use postage stamps. He sent down

to the post office department and purchased a quantity of stamps. He then ordered up a package of the paper upon

which government securities were printed. He cut this into various sizes and then on the pieces he pasted stamps to

represent different amounts. He thus invented a substitute for fractional silver.

Spinner’s initial idea was to paste period postage stamps onto cut pieces of U.S. Treasury letterhead. The

crude proofs shown are from the archives of the National Numismatic Collection of the Smithsonian’s Museum of

American History. They came from Herman Crofoot who donated Spinner’s personal collection of postage stamp

mock-ups and currency proofs to the Smithsonian in the 1960s. Spinner’s designed mock-ups depicts all 4

denominations: 5, 10, 25 and 50 cents. The 50¢ contains Spinner’s signature approving the design. All 4

denominations were mounted on a single large card; we’ve digitally cut the images to provide more detail. A rough

design, but he was on the right track.

The next piece with an unknown origin, was from the Stack’s sale of John Ford’s collection. It is an

extraordinary and historically crucial experimental essay used in the development of postage currency. Unlike all

previous coin replacement ideas, this piece has no mercantile connection suggesting that is was quite possibly

created by the National Bank Note Company (aka NBNC) for Spinner as a way to progress the Treasurers’ original

idea (pasting stamps onto Treasury paper).

Telltale signs like the heavy bond paper and the “Patent Pending” on the right side are strong clues. Note

the outlines reserved for postage stamps and the title in script indicating “United States 25 Cents Legal Tender”.

On the bottom, in block letters, “POSTAGE STAMP CURRENCY” suggests that the NBNC presented this to

Spinner as their concept of how federally issued postage stamp currency could look. By pasting (five) 5¢ stamps

in the outlines, a 25¢ postage stamp currency note is created.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

321

This design was never advanced but with the stamps attached the note would have appeared like this:

While Spinner was on the right track, he realized early on that these early proofs and essays were not

sustainable. Having to glue millions of stamps onto millions of pieces of Treasury paper was not a viable and

sustainable solution. Then he came up with the “EUREKA!!” moment. As with most great ideas, the key

component of success is simplification. Instead of attaching stamps to a piece of Treasury paper, why not print the

currency with the images of the stamp? It was sublimely simple and brilliant. In a 2 step printing process (front

and back) a sheet of postage currency could be easily produced. It was efficient, cost effective and most importantly

great quantities could be produced quickly…something the country urgently needed.

Shown is the next step in the process

towards the finished product. The 50¢

example is a work in progress “Postage

Stamp” proof. With close inspection, we can

see that the “50” on the top corners are hand

inked and glued onto the proof. The “US”

shield below the center stamp is glued onto

the proof too.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

322

Citing Tom O’Mara’s article from SPMC Paper Money January/February 2003:

The following four notes are examples of artist designs, which are partially drawn or hand pasted notes.

These notes combine both hand drawn and cutout printed design pieces pasted onto cardboard. For example, on

the 5¢ note the center stamp vignette, the “5” on dies on either side, and the four-corner scroll work, are pasted

on printings, while the borders and wording are hand drawn with a watercolor type ink. On the 10¢ artist design

the top corner paste on scroll work fell off over the years.

The positioning of the “POSTAGE STAMP” titles are different on the next 25¢ progress proofs. Notice the

fonts change from a solid form to an open outline.

With a clear vision, Spinner mobilized to produce specimen proofs, something that Congress would approve.

His initial proofs are remarkably similar to the final circulating examples. One of the major difference is on the

top of the note. The initial proofs were called “POSTAGE STAMPS”...the final circulating notes were renamed

“POSTAGE CURRENCY”.

The other difference is on the bottom left of the Postage Stamp note; the familiar “NATIONAL BANK

NOTE” imprint is missing. Regular first issue obverses all have the NBNC imprint, the early proofs do not.

With these hand worked artist drawn proofs deemed acceptable, Spinner had the following proofs printed.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

323

Note that there is a pencil “X” on top of “STAMPS” and a pencil inscription to the immediate right that states

“CURRENCY”. The idea to change the title from “STAMPS” TO “CURRENCY” was logical. Postage Currency

was a Treasury product and not a U.S. Post Office product. In future issues (2nd

– 5th), Postage Currency was

renamed Fractional Currency. The nomenclature “POSTAGE” and “STAMPS” was abandoned forever and all

ties to the Postal Service were severed.

There are 2 examples of postage currency proof

reverses donated by Crofoot. These earliest of examples currently reside at the Smithsonian. Like the obverses

shown above, they are mounted on cardboard and show similar foxing. Both contain a pencil notation simply

stating “Back.”

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

324

It should be noted that there were several versions of essays produced, some on different paper and several

with different color inks. These very rare essays contain the original design but were printed in green ink. They

were never adopted, but it shows how Spinner was experimenting.

From the 2005 O’Mara sale is a postage

currency essay printed on white paper (as

opposed the tan paper used in the regular issue)

and printed in black ink. A unique variant that

was never adopted.

From the 1904 Chapman and the 1997

Friedberg sales is a fascinating 5¢ essay printed on

a soft yellow paper and a dull black ink (instead of

the brown ink we see on regular issue postage

currency).

DESIGN COMPLETED

With design set and the word “STAMPS” at the note’s top jettisoned, Spinner had quite a few narrow and

wide margin “POSTAGE CURRENCY” specimens made by the National Bank Note Company. They are the

final test pieces before circulating currency was issued.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

325

The reverse contain no NBNC imprint, however as a security measure during the regular issue production

of Postage Currency the reverses were printed by the American Bank Note Company which explains why there

are some reverses with the monogram (ABNC) and some without (NBNC).

Once in production the Treasury printed nearly 125 million Postage Currency notes. The breakdown per

denominations is as follows:

Value Number Issued

5¢ 44,857,780

10¢ 41,153,780

25¢ 20,902,784

50¢ 17,263,344

From a historical perspective the contribution made by Spinner is remarkable bordering on miraculous.

When one considers all the flawed stopgap measures undertaken by enterprising Americans during the early

1860’s, what Spinner accomplished makes this one of the great achievements of the 19th century. Spinner led

the way in stabilizing the U.S. economy during a very tenuous time (Civil War era) and placed control of the

U.S. circulating money supply back where it belongs… in the hands of the U.S. Treasury, where it still

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

326

resides today. Imagine going into a store buying some goods and not knowing if you were going to receive token,

stamps, encased postage, private scrip, etc. in change. Unnerving indeed. The U.S. public didn’t love postage

and fractional currency, but it was a huge improvement and was widely accepted until 1876, when circulating

coins were available in enough quantities to finally retire fractional currency. Thank you General Spinner!

A great deal of thanks and support has to be extended in composing this article. First on the list is FCCB

fractional newsletter editor Jerry Fochtman. Jerry’s tireless fight to make a lot of the images available to the

community are to be recognized. Next a thank you to Jennifer Gloede from the Smithsonian for providing the

Crofoot images. Thanks also the SPMC editor Benny Bolin for his encouragement, the dearly departed Matt

Rothert and Milton Friedberg for their research on the subject. Also to former FCCB President Tom O’Mara for

first bringing the Crofoot images to the public and to the wonderful Heritage and Stack’s Bowers archives which

contain a treasure trove of information. Last, but certainly not least, a big debt of gratitude for my son David’s

excellent editing skills.

W_l]om_ to Our

N_w M_m\_rs!

\y Fr[nk Cl[rk—SPMC M_m\_rship Dir_]tor

NEW MEMBERS 07/05/2019

PM14979 Joe Gorak,, Website

PM14980 Lawrence Povlow, Website

PM14981 John DiLoreto, Website

PM14982 Mary G. Holland, Richard Self

PM14983 Mark de Jeu, Mark Drengson

PM014984 Jim Bernstein, Website

PM014985 Sev Onyshkevych, IPMS Show

PM014986 Andrew Timmerman, Cody Regennitter

PM014987 Robert Wheless, Website

PM014988 Michael Granberg, Shawn Hewitt

PM014989 Richard Hunter, Frank Clark

PM014990 Tim O'Keefe, Robert Moon

PM014991 John D. Oxford, Robert Calderman

PM014992 Eugene Rowe, Gary Dobbins

PM014993 Bobby Swicegood, Website

PM014994 James Tremaine, Robert Calderman

PM014995 Allan Craven, Website

PM014996 John Grost, Website

PM014997 James Carroll, Website

NEW MEMBERS 08/05/2019

PM014998 Kevin Rumes, Harry Jones

PM014999 Mitchell Davis, Website

PM015000 Kirk Jackson, Website

PM015001 Salvatore Germano Jr, Don Kelly

PM015002 Terry Dodd, Robert Calderman

REINSTATEMENTS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

None

REINSTATEMENTS

None

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

327

Treasury sealing

assigned to Treasurer’s office

in 1885

Introduction and Purpose

The sealing of Treasury currency and certificates was reassigned from the Bureau of Engraving

and Printing to the Treasurer’s office in 1885.

The purpose of this article is to explain why this was done and how it impacted Treasury currency.

The key person responsible for this change was Edward O. Graves, an employee of the Department

of Treasury who was a champion for efficiency and Civil Service status for all Treasury employees. Graves

served as a trouble shooter for Secretary of the Treasury William Sherman, which resulted in two reports

that were highly critical of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in 1877 and 1881. His reward was to be

appointed Chief of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in 1885, a position he held until 1889, wherein he

implemented many of his proposed reforms, among them the transfer of the sealing currency out of the BEP

to the Treasurer’s office.

Treasury Currency

Treasury currency is currency that Congress authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to issue. It

included demand notes (1861-1862), legal tender notes (1862-1971), gold certificates (1863-1934), silver

certificates (1878-1963) and Treasury notes (1890-1893).

Congress also authorized the issuance of bank currency, which encompassed national bank notes

(1863-1935) and Federal Reserve notes (1913-present). Federal Reserve bank notes, an emergency

supplemental currency with backing similar to national bank notes, were current during 1915-1923 and

1933-1934,

The difference between these classes of currency was who was obligated to redeem the notes into

legal money. The Treasury itself carried the obligation for all Treasury currency. The bankers were

obligated in the case of the bank currency, although ultimate liability for the Federal Reserve notes rests

with the United States.

The Paper

Column

by

Peter Huntoon

Doug Murray

Figure 1. This is the very first $20 silver certificate that was sealed in the Treasury building

after responsibility for sealing was transferred to the Treasurer’s office from the Bureau of

Engraving and Printing in 1885. It carries a small round red Treasury seal because that seal

didn’t become available until 1886 before the order containing this note was executed. Heritage

Auction archives photo.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

328

Only Treasury currency was affected by the events described in this article. Sealing of national

bank notes continued to be carried out at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing because those notes weren’t

considered to be complete unless signed by the issuing bankers.

The Big Picture

When John Sherman was appointed Secretary of the Treasury by Republican President Rutherford

B. Hayes in March 1877, the employment rolls of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing were bloated with

patronage appointees and the Bureau was under fire for lax security. Hays advocated in his campaign for a

monetary gold standard and for civil service reform in order to base Federal employment on merit rather

than political patronage. Former Ohio Congressman and Senator John Sherman was a like-minded

Republican who upon appointment as Secretary used his position to further the goals of hard money and

fiscal responsibility as Treasury policy.

Immediately upon taking office in March 1877, Secretary Sherman appointed a committee of three,

chaired by Edward Graves, to examine the operations of the Bureau. The other members were Edward

Wolcott of the Comptroller of the Currency’s office and E. R. Chapman of the Internal Revenue

Commissioner’s office.

Graves had been hired as a clerk under Francis E. Spinner in the Treasurer’s office in 1863. He was

promoted to chief clerk in 1868 and then moved on to become chief examiner of the Civil Service

Commission. On July 1, 1874, he was appointed as the first superintendent of the newly organized National

Bank Redemption Agency within the Treasurer’s office mandated by the Act of June 20, 1874, which

provided for an expedited procedure for removing unfit national bank notes from circulation (BEP, 2004).

Graves was the ideal candidate to spearhead Sherman’s reviews, having an intimate knowledge of the inner

workings of the Treasury Department and progressive views toward reforming it.

What the 1877 committee found in terms of employment was a Bureau payroll bloated by lavish

Congressional appropriations that were in turn used to cover appointments made to the workforce on the

behalf of Congressmen “without the regard to the fitness of the appointees or the necessities of the work. *

* * Moreover, the Bureau has been made to subserve, to a great extent, the purposes of an almshouse or

asylum” (Graves and others, 1877, p. 9). The issue was job creation under the political spoils system

whereby Congressmen with a sympathetic ear were finding employment for Union veterans and

constituents left bereft from the Civil War by death or infirmity of providers who served the Union.

The following examples were provided (Graves and others, 1877, p. 8).

We are informed and believe that the force employed in some divisions was for a number of years

together twice as great as was required for the proper performance of the work, and that in others it was

three times as great as necessary. In one of these divisions a sort of platform had been built underneath the

iron roof, about seven feet above the floor, to accommodate the surplus counters. On this shelf, on parts of

which a person of ordinary height could not stand erect—deprived of proper ventilation, and exposed in

summer to the joint effects of the heated roof above and the fumes of the wetted paper beneath—were

placed some thirty or more women who had received appointments, and for whom room must be found. *

* * the surplus force stowed away in the loft was entirely unnecessary; and that some of them, at times for

lack of occupation, whiled away the time in sleep.

* * *

In the printing division we found twenty female messengers, sixteen of whom were ostensibly

engaged in taking the sheets, as received from the printers, to the examining division. As soon as a few

hundred sheets were ready they were taken up on a board and carried by a messenger through a narrow

passage to the examiners. The messengers were so numerous as to be actually in each others’ way. On our

recommendation they have all been discharged and replaced by one man, who takes all the sheets to the

examiners on a truck, and finds time for other work besides.

Secretary Sherman was so intent on implementing reforms at the BEP that he began instituting

changes being suggested by the committee before the report was finalized or published. In the realm of

employment, the workforce at the Bureau was reduced from 958 on April 1, 1877 to 367 by June 10th when

the report was submitted for publication (Graves and others, 1877). This constituted a 62 percent reduction

of the workforce. More reductions followed.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2019 * Whole No. 323_____________________________________________________________

329

The committee also examined practices that would provide security against fraudulent issues,

which led them to question why Congress had been progressively assigning more work on the notes to the

Bureau. The committee concluded “the public confidence in such security would be promoted by a division

of the work between Government and private agencies, each of these agencies doing one or more of the

printings necessary to wholly complete any obligation of the Government. * * * we accordingly recommend

that at least one plate-printing on all legal-tender notes, national-bank notes, and United States bonds, be

executed by capable, experienced, and responsible bank-note companies; and that, if it should be thought

advisable to have a greater number of printings done outside of the Bureau, no company be permitted to

execute more than one of them upon any obligation. * * * To obtain the full measure of security

contemplated by this plan, the plates with which each establishment does its portion of the printing should

be prepared by itself, and, together with the stock used in their preparation, should remain in its custody”

(Graves and others, 1877, p. 12-13).

The purpose for printing Treasury seals on notes was to indicate that they were lawful issues. The

responsibility for printing the Treasury seals on legal tender notes was assigned to the National Currency

Bureau within the Treasury Department in 1862, a practice deemed appropriate because the seals were the