Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

Vignette and Other Engraving Varieties--Peter Huntoon

Bankers Go for Outing--End Up in Jail--Nick Bruyer

Major Upham's Coupons--Terry Bryan

Sears Customer Profit Sharing Certificates--Loren Gatch

Circulation of the State Bank of Iowa--James Ehrhardt

Wooden Nickels--Clifford Thies

The Mauch Chunk National Bank-- Michael Saharian

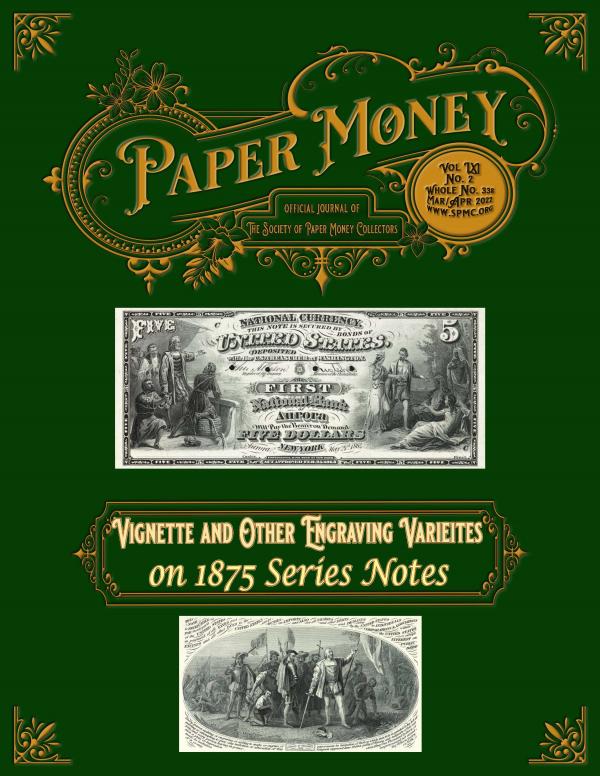

official journal of

The Society of Paper Money Collectors

Vignette and Other Engraving Varieites

on 1875 Series Notes

1550 Scenic Avenue, Suite 150, Costa Mesa, CA 92626 • 800.458.4646

470 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10022 • 800.566.2580 • NYC@StacksBowers.com

1735 Market Street, Suite 130, Philadelphia, PA 19103 • 800.840.1913 • Philly@StacksBowers.com

Info@StacksBowers.com • StacksBowers.com

California • New York • Philadelphia • New Hampshire • Oklahoma • Hong Kong • Paris

SBG PM Spring2022 220301

America’s Oldest and Most Accomplished Rare Coin Auctioneer

LEGENDARY COLLECTIONS | LEGENDARY RESULTS | A LEGENDARY AUCTION FIRM

Contact Us for More Information Today!

800.458.4646 West Coast • 800.566.2580 East Coast • Info@StacksBowers.com

The Stack’s Bowers Galleries

Spring 2022 Showcase Auction

T-2. Confederate Currency. 1861 $500.

PMG Very Fine 25.

Fr. 314. 1886 $20 Silver Certificate.

PCGS Banknote Choice Uncirculated 64.

T-3. Confederate Currency. 1861 $100.

PMG Choice Uncirculated 63.

Fr. 260. 1886 $5 Silver Certificate.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Fr. 355. 1890 $2 Treasury Note.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 66 EPQ.

Fr. 63a. 1863 $5 Legal Tender Note.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 66 EPQ.

Fr. 2200-Idgs. 1928 $500 Federal Reserve Note.

Minneapolis.

PMG Choice Uncirculated 64 EPQ.

Fr. 613. White Plains, New York.

$10 1902 Red Seal. First National Bank.

Charter #6351. PMG Very Fine 20.

Fr. 598. Ossining, New York. $5 1902 Plain Back.

First NB & TC. Charter #471.

PMG Choice About Unc. 58EPQH.

Serial Number 1.

Auction: April 5-8, 2022 • Costa Mesa, CA

FEATURED HIGHLIGHTS

108

Vignette & Other Engraving Varieties--Peter Huntoon

Bankers Go for Outing-Wind Up in Jail--Nick Bruyer

Major Upham's Coupons--Terry Bryan

Circulation of the State Bank of Iowa--James Ehrhardt

Sears Customer Profit Sharing Certificates--Loren Gatch

124

86

116

120

133 Wooden Nickles--Clifford Thies

135 The Mauch Chunk National Bank--Michael Saharian

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

81

Columns

Advertisers

SPMC Hall of Fame

The SPMC Hall of Fame recognizes and honors those individuals who

have made a lasting contribution to the society over the span of many years.

Charles Affleck

Walter Allan

Doug Ball

Joseph Boling

F.C.C. Boyd

Michael Crabb

Forrest Daniel

Martin Delger

William Donlon

Roger Durand

C. John Ferreri

Milt Friedberg

Robert Friedberg

Len Glazer

Nathan Gold

Nathan Goldstein

James Haxby

John Herzog

Gene Hessler

John Hickman

William Higgins

Ruth Hill

Peter Huntoon

Don Kelly

Lyn Knight

Chet Krause

Allen Mincho

Clifford Mishler

Judith Murphy

Dean Oakes

Chuck O’Donnell

Roy Pennell

Albert Pick

Fred Reed

Matt Rothert

Herb & Martha

Schingoethe

Hugh Shull

Glenn Smedley

Raphael Thian

Daniel Valentine

Louis Van Belkum

George Wait

D.C. Wismer

Robert Vandevender 83

Benny Bolin 84

Frank Clark 85

138

From Your President

Editor Sez

New Members

Uncoupled

Obsolete Corner

Joe Boling & Fred Schwan

Robert Gill 146

Quartermaster Column Michael McNeil 148

152

154

Cherry Pickers Corner

Chump Change

Loren Gatch

Robert Calderman

Stacks Bowers Galleries IFC

Pierre Fricke 81

PMG Currency 107

Lyn Knight 115

Richard Whitmire 119

ANA 145

Denly's of Boston 155

Evangelisti 155

Higgins Museum 155

Vern Potter 156

Fred Bart 156

FCCB 156

Bob Laub 156

157PCDA

Heritage Auctions OBC

Fred Schwan

Neil Shafer

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

82

Officers & Appointees

ELECTED OFFICERS

PRESIDENT

rvpaperman@aol.com

VICE-PRES/SEC'Y Robert Calderman

gacoins@earthlink.net

TREASURER Robert Moon

robertmoon@aol.com

BOARD OF GOVERNORS

Mark Anderson mbamba@aol.com

Robert Calderman gacoins@earthlink.net

Gary Dobbins g.dobbins@sbcglobal.net

Matt Drais stockpicker12@aol.com

Mark Drengson markd@step1software.com

Pierre Fricke

aaaaaaaaaaaapierrefricke@buyvintagemoney.com

Loren Gatch lgatch@uco.edu

William Litt Billlitt@aol.com

J. Fred Maples maplesf@comcast.net

Cody Regennitter cody.regennitter@gmail.com

Wendell Wolka purduenut@aol.com

APPOINTEES

EDITOR Benny Bolin smcbb@sbcglobal.net

ADVERTISING MANAGER

Wendell Wolka Purduenut@aol.com

LIBRAIAN

Jeff Brueggeman jeff@actioncurrency.com

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

Frank Clark

IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT

Shawn Hewitt

WISMER BOOk PROJECT COORDINATOR

Pierre Fricke

From Your President

Robert Vandevender II

From Your President

Shawn Hewitt

Paper Money * July/August 2020

6

Robert Vandevender II

LEGAL COUNSEL

Megan Regennitter Megan.regenniter@mwhlawgroup.com

frank_clark@yahoo.com

Greetings: 2022 appears to be off to a great numismatic start with the SPMC

fully engaged in moving forward as coin and currency shows return. Thanks to

several of our board members, we successfully staffed a club table at the January

FUN Show in Orlando, at the Houston Show, and I plan to join Vice President

Robert Calderman at our club table during the Long Beach show.

I would like to share some great news. At our February board meeting, the

SPMC board voted unanimously to hold our next annual meeting during an

upcoming show scheduled for a few months away. We are planning for this

show to be accompanied by the many events we have held in the past such as

exhibit judging, award presentations, a Hall of Fame Dinner, and our well-known

SPMC Breakfast with the associated fund-raising raffle. We will, of course, be

seeking the services of Governor Wendell Wolka to emcee that raffle and I am

confident he will be up to the task of providing a little entertainment as the

numbers are drawn. Once again, we will be asking for item donations from

members and dealers for the event. If Wendell were here, he would likely tell

you to get your winning number requests in early!! The planning for these events

is just now starting with much to be done so don’t jump the gun too much until

we get some arrangements in place. Watch for more details in the next Paper

Money issue.

Last month, the SPMC received a generous contribution from the National

Currency Foundation to help the SPMC continue its research activities and

publication of many great articles in the Paper Money magazine. We look

forward to many exciting new articles in this upcoming year from many of our

authors and expect to see big things once again from our Hall of Fame member

Peter Huntoon.

For those of you on social media, I hope you are having the chance to see the

Facebook “SPMC Note of the Day” provided by member Andy Timmerman. I

always enjoy seeing what he comes up with for the daily post. Postal Notes were

the flavor of today’s post. If you are not seeing our Note of the Day, be sure to

find our “Society of Paper Money Collectors” Facebook page and click the

thumbs-up like icon so the content appears in your feed.

With the help of Governor Mark Drengson, the SPMC continues working on

the development of and sponsorship of a “Collecting Paper Money” wiki website

and Bank Note History Project. Later this year, we expect to make the link

available to both members and the public. We continue to seek help from our

membership to contribute to the content development. Please contact us if you

would like to help.

Another great effort underway is the development of short educational videos.

The first of those videos has been developed by Governor Loren Gatch with help

from college students and is currently being reviewed. The subject for this first

video is Depression Script and, I must admit, I learned quite a bit while watching

it. At some point, we will be providing a link to this and upcoming videos on our

website as well as offering them as an outreach to other collector clubs to provide

an entry level insight into the various paper money collecting areas. I urge you to

check it out when it is posted.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

83

Terms and Conditions

The Society of Paper Money Collectors (SPMC) P.O. Box 7055,

Gainesville, GA 30504, publishes PAPER MONEY (USPS 00‐

3162) every other month beginning in January. Periodical

postage is paid at Hanover, PA. Postmaster send address

changes to Secretary Robert Calderman, Box 7055, Gainesville,

GA 30504. ©Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc. 2020. All

rights reserved. Reproduction of any article in whole or part

without written approval is prohibited. Individual copies of this

issue of PAPER MONEY are available from the secretary for $8

postpaid. Send changes of address, inquiries concerning non ‐

delivery and requests for additional copies of this issue to

the secretary.

MANUSCRIPTS

Manuscripts not under consideration elsewhere and

publications for review should be sent to the editor. Accepted

manuscripts will be published as soon as possible, however

publication in a specific issue cannot be guaranteed. Opinions

expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect those of the

SPMC. Manuscripts should be submitted in WORD format via

email (smcbb@sbcglobal.net) or by sending memory stick/disk

to the editor. Scans should be grayscale or color JPEGs at

300 dpi. Color illustrations may be changed to grayscale at the

discretion of the editor. Do not send items of value.

Manuscripts are submitted with copyright release of the author

to the editor for duplication and printing as needed.

ADVERTISING

All advertising on space available basis. Copy/correspondence

should be sent to editor.

All advertising is pay in advance. Ads are on a “good faith”

basis. Terms are “Until Forbid.”

Ads are Run of Press (ROP) unless accepted on a premium

contract basis. Limited premium space/rates available.

To keep rates to a minimum, all advertising must be prepaid

according to the schedule below. In exceptional cases where

special artwork or additional production is required, the

advertiser will be notified and billed accordingly. Rates are

not commissionable; proofs are not supplied. SPMC does not

endorse any company, dealer, or auction house. Advertising

Deadline: Subject to space availability, copy must be received

by the editor no later than the first day of the month

preceding the cover date of the issue (i.e. Feb. 1 for the

March/April issue). Camera‐ready art or electronic ads in pdf

format are required.

ADVERTISING RATES

Editor Sez

Benny Bolin

What A Start!

2022 is certainly off to a great start. I was able to attend the

January FUN show and it really was fun, fun, fun. I was only there for

Friday and Saturday but being back to a major show was great. I only

spent $70 on three small fractional manuscript notes but at this stage

of my collecting career, going to shows is mostly about renewing

friendships and catching up! FUN is a very well run show and my hat

is off to the organizers for making this a most memorable experience.

The SPMC had a general meeting with a nice presentation by Robert

Calderman. Many wonderful exhibits were placed with a strong show

by paper collectors. Dennis Schafluetzel, Bob Moon and Jerry

Fochtman were all winners—congratulations!

Speaking of shows, the SPMC board of governors had a

meeting in February and we voted to once again bring back our

normal IPMS activities, including the general membership meeting,

breakfast with award presentations and the Tom Bain raffle (mix ‘em

up!) featuring our own incomparable and always enjoyable emcee

Wendell Wolka! Be on the look out for more details as to when and

where coming soon.

It is my sad duty to inform you of yet another stalwart of the

society’s passing—Roger Durand. Roger served the society in many

capacities and literally wrote the book on Rhode Island obsoletes and

a series on vignettes which I have used a lot in my collecting of South

Carolina vignettes. Roger will be missed.

I am still in need of new articles, especially those of 1-5 pages.

As you can see from the last few issues, I have a good supply of larger

articles, but need those shorter ones. Articles written by our members

are what make our publication great!

I have to tell on myself for two kinda faux pas. The first was in

the FUN auction. There was a fractional note with an inverted

surcharge that this example is only the second known. I fought for it

and in my opinion overpaid but I really wanted it. I got it and when it

arrived, I was looking at it and guess what? I found the other known

one in MY OWN COLLECTION! The other happened just a couple

of weeks ago in a Tuesday night HA auction. I had just found an

invert that I did not have and wanted it. But, I was bowling as a sub

for my wife's and son's team and it came up for auction but it was

my time to bowl. So, I told my wife and son to bid for me to a

max of $300. And boy did they. I could see they were having from

the lane and were they ever! To the tune of almost $600! Said they

got caught up with auction fever! Oh well, at least the consignor was

happy.

Until next issue! Be safe, have fun and love those notes!

Required file submission format is composite PDF v1.3

(Acrobat 4.0 compatible). If possible, submitted files should

conform to ISO 15930‐1: 2001 PDF/X‐1a file format standard.

Non‐ standard, application, or native file formats are not

acceptable. Page size: must conform to specified publication

trim size. Page bleed: must extend minimum 1/8” beyond

trim for page head, foot, and front. Safety margin: type and

other non‐bleed content must clear trim by minimum 1/2”.

Advertising c o p y shall be restricted to paper currency, allied

numismatic material, publications, and related accessories.

The SPMC does not guarantee advertisements, but accepts

copy in good faith, reserving the right to reject objectionable

or inappropriate material or edit copy. The SPMC

assumes no financial responsibility for typographical

errors in ads but agrees to reprint that portion of an ad in

which a typographical error occurs.

Benny

Space

Full color covers

1 Time

$1500

3 Times

$2600

6 Times

$4900

B&W covers 500 1400 2500

Full page color 500 1500 3000

Full page B&W 360 1000 1800

Half‐page B&W 180 500 900

Quarter‐page B&W 90 250 450

Eighth‐page B&W 45 125 225

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

84

WELCOME TO OUR

NEW MEMBERS!

BY FRANK CLARK

SPMC MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

NEW MEMBERS 01/05/2022

15370 Thomas Mendenhall, R Calderman

15371 Steven Moore, Rbt Calderman

15372 George W. Goodlow, BNR Ad

15373 Lindsay Robertson, Website

15374 Kippen Wills, Website

15375 Stan Ryckman, Website

15376 Jason Kaar, Frank Clark

15377 Gerald Naylor, Website

15378 Stefan Jovanovich, Website

15379 Dale White, Frank Clark

15380 Chris Seuntjens, Frank Clark

15381 Bret Bryson, Rbt Calderman

15382 Stephen Yozaites, Website

NAME CORRECTION

15367 Raymond Lam

REINSTATEMENTS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

LM460 Chris Bulfinch, Website

NEW MEMBERS 02/05/2022

15383 Brent Sobol, Frank Clark

15384 Steve Costner, John A. Parker

15385 Bernard Ososky, John Bremer

15386 Marshall Mallory, Frank Clark

15387 Kert Phillips, Frank Clark

15388 William Adney, ANA Ad

15389 Andrew Pappacoda, Frank Clark

15390 Josh Mathely, Rbt Calderman

15391 Tyson Flugstad, Rbt Calderman

15392 Carter McDonald, Rbt Calderman

15393 James Adams, Website

15394 Sullivan Labno, Fricke/Hewitt

15395 Robert Mellichamp, Gary Dobbins

15396 Imtiaz Khokhar, Website

15397 Robert Bruner, Facebook

15398 John Smith, Rbt Calderman

15399 Joe Lewis, Website

REINSTATEMENTS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

None

Dues Remittal Process

Send dues directly to

Robert Moon

SPMC Treasurer

104 Chipping Ct

Greenwood, SC 29649

Refer to your mailing label for when your

dues are due.

You may also pay your dues online at

www.spmc.org.

The Society of Paper Money

Collectors was organized in 1961 and

incorporated in 1964 as a non-profit

organization under the laws of the

District of Columbia. It is

affiliated with the ANA. The

Annual Meeting of the SPMC is

held in June at the International

Paper Money Show. Information

about the SPMC, including the by-

laws and activities can be found

at our website-- www.spmc.org.

The SPMC does not does not

endorse any dealer, company or

auction house.

MEMBERSHIP—REGULAR and

LIFE. Applicants must be at least 18

years of age and of good moral

character. Members of the ANA or

other recognized numismatic

societies are eligible for membership.

Other applicants should be sponsored

by an SPMC member or provide

suitable references.

MEMBERSHIP—JUNIOR.

Applicants for Junior membership

must be from 12 to 17 years of age

and of good moral character. A parent

or guardian must sign their

application. Junior membership

numbers will be preceded by the letter

“j” which will be removed upon

notification to the secretary that the

member has reached 18 years of age.

Junior members are not eligible to

hold office or vote.

DUES—Annual dues are $39. Dues

for members in Canada and Mexico

are $45. Dues for members in all

other countries are $60. Life

membership—payable in installments

within one year is $800 for U.S.; $900

for Canada and Mexico and $1000

for all other countries. The Society

no longer issues annual membership

cards but paid- u p members may

request one from the membership

director with an SASE.

Memberships for all members who

joined the Society prior to January

2010 are on a calendar year basis

with renewals due each December.

Memberships for those who joined

since January 2010 are on an annual

basis beginning and ending the

month joined. All renewals are due

before the expiration date, which can

be found on the label of Paper

Money. Renewals may be done via

the Society website www.spmc.org

or by check/money order sent to the

secretary.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

85

Vignette and other

Engraving Varieties

on $5 Original and 1875 Series Notes

ABSTRACT

A rich trove of engraving varieties produced by Continental Bank Note Company engravers occur

on the Original Series and Series of 1875 national bank note $5s.

Four different pairs of vignettes are found on the faces. Each pair was made from a different full-

face master die.

The backs are even more complicated. Three distinct engravings were used to print the vignette,

which were mated on plates in various permutations with three distinct engravings for the use and

counterfeit statements that surround the vignette.

The $5s carry an act approval date, unlike the other denominations in the series and it changed from

February 25, 1863 to June 3, 1864. It occurs in the lower border on the faces and in the counterfeit statement

inside the lower right back border.

Figure 1. The face of this note, bearing the second title for this Watkins bank, was printed at the end of the

Original Series in 1875 from an altered plate that originally carried The Second National Bank title. The bank

was the last to receive notes bearing an 1863 act approval date on the face so, being an altered plate, that old

act date and variety 2 face vignettes were preserved on it. The extensively used variety C vignette on the back

coupled with variety 3 wording for the counterfeiting statement with June 3, 1864 act approval date seems mis-

mated with the face. The New York coat-of-arms is the early variety. Somewhere in its journey, U. S. Treasurer

John Burke, who served between 1913 and 1921, autographed the face. Heritage Auction Archives photo.

The Paper

Column

Doug Walcutt

Peter Huntoon

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

86

All of these varieties appeared within 20 months of the start of the Original Series.

A minor intaglio design alteration involved the Continental Bank Note Company imprint, which

began to be omitted from the bottom border of Series of 1875 faces beginning in February, 1887, but not

always.

PURPOSE, BACKGROUND AND ORGANIZATION

The purposes of this article are to profile the engraving varieties found on the faces and backs of

Original/1875 $5s, explain when they came about and reveal what we know about the usage for each.

The difference between the Original Series and Series of 1875 was that the Series of 1875 was

established to identify the notes where at least the intaglio faces had been printed by the Bureau of

Engraving and Printing. Private bank note companies did all the intaglio work on the Original Series notes.

An Act passed by Congress and signed into law on March 3, 1875 required that “the final printing and

finishing [of national bank notes was] to be executed in the Treasury Department.”

On January 4, 1877, Secretary of the Treasury Lot M. Morrill ordered that all back plates from the

bank note companies be turned over to the Bureau, except for the vignettes on the backs of the $5s (BEP,

various dates-a). Consequently, the Bureau began printing the national bank note backs beginning in

January 1877, and simultaneously assumed responsibility for making new back plates as needed. The black

vignettes on the $5 backs continued to be printed by the Columbian Bank Note Company in Washington,

DC, through July 1877 (Dillistin, 1956), after which those plates also were turned over to the Bureau.

Three engravings dominate the $5 notes; respectively, Columbus in Sight of Land—left front;

America Presented to the Old World—right front; and The Landing of Columbus—back. They were

engraved by engravers employed by the Continental Bank Note Company, which was awarded the contract

for producing the $5 Original Series notes. What little is known about the identity of the engravers is found

in Hessler (2004) and Hessler and Chambliss (2006).

Walcutt (1996a) revealed that four different pairs of vignettes are found on the faces of the $5s.

Hessler (2004), in his first edition in 1979, cited observations by Glenn E. Jackson that three different

vignettes were used on the backs. Walcutt (1996b) profiled the back vignettes in more detail. This article

expands on and updates the foundation laid by Walcutt.

From the outset, it was apparent that the face vignettes on the Original/1875 $5 notes came in mated

pairs, of which there are four. The reason for this is that the Continental Bank Note Company produced

four distinct full-face generic master dies between mid-1863 and October, 1864 to make their plates. Each

of those dies sported a different pair of vignettes. Proofs lifted from two of them are known; specifically,

Figure 2. Proof from the variety 2 Original Series full-face master die produced at the

Continental Bank Note Company from which at least one roll was made that was used to make

5-5-5-5 plates until August, 1864. Notice that the signatures of Chittenden and Spinner were

engraved into the die, a fact that caused headaches in the future when the signatures had to

be changed on the plates. Heritage Auction Archives photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

87

varieties 2 and 4, shown here as Figures 2 and 3.

The face and back plate varieties along with when they were used will be will be profiled in Parts

I and II, respectively. The protocols that guided the manufacture of face plates will be covered in Part III

including identification of exotic situations that developed. The contracts for the Original Series $5s were

awarded to the Continental Bank Note Company, the only national bank note denomination assigned to that

company, so a brief examination of Waterman Ormsby, its founder, and his influence on currency designs

follows in Part IV. This is a long article with complicated material, so these subdivisions are designed to

break it up into manageable pieces.

Part I

$5 FACE VARIETIES

The four $5 face varieties are defined on the basis of the distinctively different pairs of engravings

that were used on them. The best places to see these differences are shown on Figure 4.

The primary distinguishing features between the left vignettes are the shapes of the waves and

Figure 3. Proof from the variety 4 Original Series full-face master die produced at the

Continental Bank Note Company that was the source for all plates made in the Original Series

and Series of 1875 from the end of October 1864 until the end of the series in 1902. They also

made the mistake of engraving the signatures of the Treasury officials on this die, in this case

Colby and Spinner. Bruce Hagen photo.

Figure 4. A rare variety 1 face, readily spotted because NATIONAL CURRENCY is not

centered under the upper border. The blue ovals indicate where to look to observe the most

obvious differences between the four pairs of engravings used on Original/1875 series faces.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

88

definition of the island on the horizon. See Figure 5.

The right vignettes are readily differentiated on the basis of the feathers on the side of the head of

the Indian princess and shape of the foliage next to the upper right counter. See Figures 6 and 7.

A careful comparison between the face varieties reveals that most of the elements on the variety 1

master die, other than the vignettes, represent an entirely different engraving or assemblage of different

engravings. In contrast, significant parts of the two vignettes are identical between all the varieties

indicating that they were engraved on separate dies. Probably rolls were lifted from those dies and the

images were laid into the four full-face master dies. Once laid-in, different engravers made material

alterations to the vignettes to render them into their variety 1, 2, 3 and 4 forms.

Figure 5. The waves are more turbulent and the island and sky are better defined on the variety 2 and 3 vignettes.

The island is ill-defined on variety 4. The varieties (1, 2, 3, 4) progress from left to right.

Figure 6. The bottom feather is missing on variety 4. The second feather up is very broad on variety 1 and small

on variety 4. Varieties 2 and 3 are indistinguishable.

Figure 7. The top branch is hook-shaped on varieties 1 and 2, which are indistinguishable. More foliage has been

added to the hooked branch on variety 3. The hooked branch has been removed from variety 4.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

89

Variety 1

Variety 1 occurs only on a few of the first plates made in the Original Series. The act approval date

is always February 25, 1863, plate date is November 2, 1863, and the Treasury signatures are Chittenden-

Spinner on the Original Series notes.

Verified occurrences in the Original Series include Youngstown, OH (3), Stamford, CT (4), Fort

Wayne, IN (11), Sandusky, OH (16), Washington, DC (26) and Indianapolis (55). The Original Series

variety 1 plates for charters 3, 4, 16 and 55 were altered for use in the Series of 1875. All variety 1 notes

are very scarce in both the Original and 1875 series owing to the small number of banks that received them.

A variety 2 duplicate plate was made for The First National Bank of Washington, DC (26), early

in the Original Series. Consequently, only the early $5s issued from the bank are variety 1.

Distinguishing Features: Figure 8 reveals

that the most readily observable difference on variety

1 faces is the fact that NATIONAL CURRENCY is

not centered below the upper border and there is a

leftward shift of the lines of text above and below

UNITED STATES.

The second feather up on the side of the head

of the Indian princess is unusually broad in the right

vignette. Also, the upper branch has a distinctive hook

shape, a characteristic also common to variety 2. The

sky in the left vignette is very light down to the

horizon. Both vignettes were extended close to the

bottom border, thus constricting the space for the

bank signatures.

The letters in the upper left counter are leaner

than on varieties 2, 3 and 4 as illustrated on Figure 9.

The variety 1 Chittenden-Spinner signatures

on the Original Series version of the plates differ from

those used on varieties 2, 3 and 4. Especially

noticeable are differences in punctuation, the

placement and shape of the dots over the i in Spinner,

and the finer line weight of Chittenden’s signature on

the later varieties. See Figure 10.

The use of flourishes around the left plate

letters are unique to variety 1. See Figure 8.

Figure 8. Comparison between the

securities statement on variety 1

(top) and variety 2, 3 and 4 plates.

Notice how the lines of text have

shifted between the two and that

NATIONAL CURRENCY is not

centered under the upper border on

variety 1. These two security

statements represent two entirely

different engravings.

Figure 9. Comparison between the engravings of the

counters found on variety 1 (top) and variety 2, 3 and

4 plates. Compare the girth of the letters and sizes of

the shaded hollows on the right sides of the F and E.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

90

BEP Usage: Although variety 1 plates were transferred to the BEP in 1875, it is doubtful that the

variety 1 master die or rolls lifted from it were. No proofs from the master die have been found at the BEP

and no reentries were made to the Series of 1875 forms of the variety 1 plates that were in BEP custody.

Variety 2

Variety 2 is the second most common variety, being found on most notes with charters 1 through

458. Those for charters 1 through 456 have an act date of February 25, 1863. Variety 2 vignettes also were

reentered over some Original Series plates that originally bore variety 3 vignettes.

Distinguishing Features: There is a large thin feather and one small feather on the side of the head

of the Indian princess in the right vignette. The waves in the left vignette are more turbulent than on variety

1. The hooked branch next to the upper right counter is the same as on variety 1.

BEP Usage: The variety 2 master die and/or roll(s) lifted from it were transferred to the BEP in

1875. Variety 2 vignettes were reentered as needed by BEP siderographers onto variety 2 and some variety

3 Original Series plates that had been altered into Series of 1875 forms.

Variety 3

Variety 3 was used to make the plates for charters 460 to 525, which always bear a June 3, 1864,

act date. Notes with this variety are scarce because of its limited usage.

Distinguishing Feature: The hooked branch next to the upper right counter exhibits considerably

more foliage than that on any of the other varieties.

The waves on the left vignette and feathers on the side of the head of the Indian princess are

Figure 11. Variety 2. Turbulent waves, smaller feathers on the side of the princess’ head, hooked

tree branch same as variety 1.

Figure 10. Different Chittenden-

Spinner signatures were used on

the variety 1 Original Series

notes (top) than on varieties 2, 3

and 4. Easily observed are

differences in punctuation

throughout. Also notice

differences in where the various

loops intersect overlying and

underlying text.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

91

indistinguishable from those on variety 2.

BEP Usage: Neither the variety 3 master die nor rolls lifted from it were transferred to the BEP in

1875 or they arrived in unserviceable condition. Consequently, the BEP siderographers never reentered

variety 3 vignettes onto any variety 3 Original Series plates that the BEP received.

Variety 4

Variety 4 is found on Original/1875 series notes from charters 528 through 2767, along with some

earlier charters for which new-title, late-ordered, or duplicate plates were made. Variety 4 is the most

common variety found on notes.

Distinguishing Features: There is only one feather on the side of the head of the Indian princess

and it is small. The hooked branch on the tree has been removed.

BEP Usage: The variety 4 master die and rolls(s) lifted from it were transferred to the BEP in 1875

and used to make all new plates thereafter at the BEP as well as to reenter variety 4 Original Series plates

transferred to the BEP. Variety 4 vignettes also were reentered at the BEP over variety 3 vignettes on some

plates that carried variety 3 vignettes in their Original Series form.

Figure 13. Variety 4. Bottom feather on side of head is missing, second feather up is small,

hooked branch next to upper right counter is gone, waves similar to variety 1, island is weakly

portrayed.

Figure 12. Variety 3. Decidedly fuller foliage above the hooked branch next to the upper right

counter, waves and feathers indistinguishable from variety 2.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

92

Part II

BACK VIGNETTE VARIETIES

Three different engravings of The Landing of Columbus were used on the backs of Original Series

$5 notes. They are listed here as varieties A, B and C. All were made at the Continental Bank Note

Company. All were used to print Original Series notes, but only variety C was used at the Bureau of

Engraving and Printing to print Series of 1875 notes. It is apparent that the dies and rolls for varieties A and

B were destroyed before the startup of the Series of 1875 because they were not turned over to the BEP in

July 1877 when the BEP took over the printing of the vignettes from the Columbian Bank Note Company,

which had held the printing contracts for them since September 1875 (Graves and others, 1877).

Variety A

Distinguishing Features: Columbus is wearing black pantaloons with definitive vertical white

stripes. The shading along the bottom of the vignette is dark.

Variety A was used from the beginning of the Original Series until at least the end of the un-prefixed

blue Treasury sheets serials in January 1865 based on observed notes.

Variety B

Distinguishing Features: Columbus’ pantaloons have a draped pattern overlain by definitive

strong engraved diagonal lines. The V design on his shirt is very pronounced wherein the uppermost dark

line is curved. The shading along the bottom of the vignette is dark.

The first use of variety B that we have observed dates from about March 1864 at the beginning of

the second third of the un-prefixed red Treasury sheet serial number block. They appear sporadically in

later blocks where we have observed them on notes with un-prefixed blue and A- and E-prefix serials, the

last of which dates from about March 1869 (Walcutt, 1996a). The variety was little used so notes sporting

it are very scarce.

Variety C

Distinguishing Features: Definitive is that there is very light shading along the bottom of the

vignette. The uppermost dark line on Columbus’ shirt is straight. The bold diagonal lines through

Columbus’ pantaloons found on variety B are missing.

Figure 14. Variety A: Definitive is that Columbus’ Pantaloons are black with vertical white strips. The bottom

of the vignette is darkly shaded. Mark Hotz photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

93

The first use of variety C that we have observed dates from around November 1864 on notes from

the middle of the un-prefixed blue Treasury sheet serial number block. It is the most common variety with

use spanning to the end of the Series of 1875.

Figure 15. Variety B: Columbus: dark line forming uppermost stripe on shirt is curved, pantaloons are lightly

patterned with definitive strong diagonal engraved lines. Bottom of the vignette is darkly shaded.

Figure 16. Variety C: Definitive is very light shading along the bottom of the vignette. Columbus: dark line

forming uppermost stripe on shirt is straight.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

94

Other Characteristics

There are several other minor differences between the back vignettes then those described.

Compare the various renderings of Columbus’ shirt, the small boats in the left background and differing

line work in the flag held by Columbus.

Other engravings of the vignette were produced by American Bank Note Company and Bureau of

Engraving and Printing engravers, but were not used on notes.

USE-COUNTERFEIT STATEMENT VARIETIES

The use and counterfeit statements that surround the back vignettes were laid into the vignette

plates as illustrated on Figure 16 because both were printed in black. There are three varieties of these

herein numbered 1 to 3. Varieties 1 and 2 carried an act approval date of February 25, 1863, whereas variety

3 used June 3, 1864. See Figure 17.

The distinguishing characteristics between varieties 1 and 2 are illustrated on Figure 18. Notice on

variety 1 that there are two dots under “th” and the top of the 3 in the year is round. There is only one dot

under “th” and a flat-topped 3 in the variety 2 year.

The mating of the use and counterfeit statements with a given vignette on the backs varied from

plate to plate in the Original Series. So far, we know of the following couplings: A/1, A/3, B/1, B/3, C/1,

C/2, C/3.

Variety 1 and 2 statements occur only on

Original Series notes. Use of variety 1 dated from the

beginning of the series. The earliest use of variety 2

that we have observed was coupled with the first

observed C vignette on a note numbered in the middle

of the un-prefixed blue Treasury serial number block

circa November 1864.

The last of the observed notes with variety 1

and 2 were printed in the first third of the H-block

around July 1871, which ended the use of act of 1863

approval dates in the counterfeit clauses. Up until

then, the act approval dates on the faces and backs

always were matched.

Variety 3, which carried a June 3, 1864 act

approval date, first appeared on Original Series notes

with Act of 1864 faces, the first of which were

delivered to the Comptroller of the Currency on July

15, 1864. Notes having 1863 faces were printed on

backs with variety 3 statements after stocks having

Figure 18. The top of the 3 in 1863 is round on variety

1 but flat on variety 2. Two dots underlie “th” in the

date on variety 1 but one on variety 2.

Figure 17. Detail showing a variety 1 1863 act approval date on an early Original Series $5.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

95

variety 1 and 2 backs ran out during the first third of the H-block. The earliest of these that we have seen

dates from around May 1871. The changeover was not sharp.

One result of this usage pattern is that no Original Series faces with 1864 act approval dates have

been found mated with variety 1 and 2 backs, so there are no notes with 1864 faces and 1863 backs. In

contrast, beginning in 1871, 1863 faces were mated exclusively with 1864 backs. The resulting mismatch

didn’t trouble anyone in the Treasury Department because the laws governing use and counterfeiting were

identical in the two acts.

All Series of 1875 notes have C/3 backs.

LIMITATIONS

The longevity of the use of the back-vignette plates depended on two factors. The most obvious

was when the last plates of a given variety wore out. However, there is a subtlety that introduces a joker

into this scheme. Backs were preprinted and stocked for each state and territory. Withdrawals from the

stocks were mated with faces as the print orders for those states and territories came in. The lives of the

stocks for the different states and territories were highly variable. Stocks having long lives resulted in some

very late uses of some permutations of back vignette and use-counterfeit statements. If your Original Series

note was printed before mid-1871 (H-Treasury sheet serial number block), you never know what surprise

might await you until you turn the note over.

No Continental Bank Note Company proofs or plate usage records survived. Consequently, our

knowledge of the usage patterns for the back varieties are imprecise because they are based on spotty

observations from notes and available high-resolution photos of notes. The usage ranges reported here will

change with future observations.

Part III

PROTOCOLS FOR MAKING ORIGINAL SERIES FACE PLATES

AND USAGE PATTERNS

Three variable non-bank-specific design elements were incorporated into the Original Series $5

face plates made by the Continental Bank Note Company: (1) vignette varieties, (2) Treasury signature

combinations and (3) act approval dates. Each time one of these variables was changed, the new version

was immediately implemented on the face plates made thereafter. See Table 1.

Plates for New Banks

The breaks in usage between the various permutations occur abruptly within the sequence of charter

numbers for new banks as documented on Table 1 with but two exceptions, (1) those with variety 1 vignettes

and (2) three banks chartered during the Jeffries-Spinner era. It is apparent that after an initial period of a

few months, Original Series plates for new banks generally were ordered in sequential order of their charter

numbers and made in close charter number order. Once a new design element became available, it was

adopted immediately and the old was dropped from use yielding sharp charter number breaks.

The first Original Series plates were not made in charter number order so the first deliveries of

variety 1 production arrived at the Comptroller’s office in the following order: charters 26, 55, 11, 16, 3, 4.

However, it still appears that the temporal break between the use of the variety 1 and 2 plates was sharp.

The very first plate made was for charter 26, The First National Bank of Washington, DC. It was

the desire of Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase that the first national bank notes would debut in

Washington to symbolize their national character so he requested that the Washington bank get the first

notes. This decision was not hurt by the fact that financier Jay Cook’s brother Henry was the president of

that bank, because Cook was instrumental in marketing the first bonds to fund the Civil War. Those sheets

arrived at the Treasury Department on December 18, 1863, where they were numbered and sealed. They

were delivered to the bank December 21st.

The second $5 plate was for The First National Bank of Indianapolis, charter 55. This also was not

coincidence. It happened that Comptroller of the Currency Hugh McCulloch was a prominent Indiana

banker who had been drafted by Chase from his presidency of The State Bank of Indiana to run that

operation. The first of the Indianapolis sheets arrived at the Comptroller’s office on December 24th.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

96

Vignette 2 plates followed for the infill and succeeding charters once those plates became available

at the beginning of 1864. Jay Cook’s First National Bank of Philadelphia, charter 1, got variety 2 faces but

not from the first variety 2 plate. The first $5 delivery to the Comptroller for his bank was on March 22,

1864, the 134th bank for which such a delivery was made. Instead, the Philadelphia bank had the honor of

receiving the first printings from 10-10-10-10 and 20-20-50-100 plates when production from them began.

In the cases Lake, IL (1678), Bangor, ME (1687) and Cleveland, OH (1689), which were charted

during the Jeffries-Spinner era, fabrication of their plates was significantly delayed owing to a

Congressionally mandated cap on total national bank note circulation. When the cap was lifted, variety 4

plates for those banks were made that carried the then current Allison-Spinner combination.

Title Change Plates

The protocol for handling title change plates was to update the plate dates using batch dates that

reflected when the plates were ordered and to use the Treasury signatures that were current on those dates.

The first title change to appear on a $5 plate was for charter 321 in Plattsburgh, NY, which was changed

from The Second National Bank to the Vilas National Bank in 1869. By then, variety 4 plates with 1864

act dates were in production so those features were used on the new plate along with the then current

Treasury signatures. The same was true for all the succeeding title change plates made in the Original

Series, except for one exotic case for the Havana, New York bank profiled below.

Duplicate Plates

The bank note companies were faced with making duplicate plates; however, we lack

documentation pertaining to the protocols used to make them.

We have identified two duplicate plates from the Original Series, a 5-5-5-5 for The Tenth National

Bank of the City of New York (307) found by Doug Walcutt and a 1-1-1-2 from The Mechanics National

Bank of the City of New York (1250) found by Doug Murray (Huntoon, 2019). Both carried a 2 next to

one of the plate letters on each subject, thus making them distinctive. No other such numbered Original

Series plates have been found despite a thorough search for them among the proofs, so we presume that the

practice of numbering duplicate plates were one-offs for the respective bank note companies that made

them.

Both an Original Series proof from the first $5 New York plate and a Series of 1875 proof from the

duplicate exist in the National Numismatic Collection. Differing plate margin markings unambiguously

demonstrate that they were lifted from different plates. The curious fact is that both carry variety 2 vignettes

Table 1. The timing of the adoption of new combinations of face vignette varieties, Treasury signature

combinations and act approval dates on Original Series 5-5-5-5 plates based on when sheets for newly

chartered banks bearing them began to be delivered to the Comptroller of the Currency.

Vignette Act First Delivery

Variety Date Treasury Signatures to Comptroller Impacted Charter Numbers

Chittenden-Spinner signatures became current - Apr 17, 1861

Act of Feb 25, 1863

1 1863 Chittenden-Spinner Dec 18, 1863 3, 4, 11, 16, 26, 55

2 1863 Chittenden-Spinner Jan 2, 1864 1 – 456 except 3, 4, 11, 16, 55

Act of June 3, 1864

2 1864 Chittenden-Spinner Jul 15, 1864 457-458 (459 unknowna)

3 1864 Chittenden-Spinner Aug 19, 1864 460-493

Colby-Spinner signatures became current - Aug 11, 1864

3 1864 Colby-Spinner Sep 2, 1864 494-525 (526, 527 unknowna)

4 1864 Colby-Spinner Oct 31, 1864 528-1672

Jeffries-Spinner signatures became current - Oct 5, 1867

4 1864 Jeffries-Spinner Dec 23, 1867 1674, 1677, 1681-1686, 1688, 1690-1691

Allison-Spinner signatures became current - Apr 3, 1869

4 1864 Allison-Spinner Jul 17, 1869 1678, 1687, 1689, 1692-2280

and 2nd titles for 94, 321, 343, 358, 420, 456, 616, 810, 826, 938,

1207, 1348, 1464, 1701, 1772, 1773, 1830, 1893, 1894, 2008

a. Type unknown- no proofs or reported specimens.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

97

and 1863 act dates. The roll with these features went out of service for making plates for new banks in June

1864, but remained in inventory.

Two scenarios are possible. (1) The first plate prematurely wore out or became damaged before

August 19, 1864, when deliveries of the first variety 3 notes began so the duplicate was made before then.

(2) The duplicate was made later so the siderographer retrieved the obsolete variety 2 roll to make the

duplicate in his effort to preserve the required Chittenden-Spinner signatures and in the process also

preserved the 1863 plate date. The only reported note from the first plate bears Treasury serial 975084-red

numbered in late July 1864, whereas the lowest reported note from the duplicate plate is P39887 numbered

in early 1875. The information provided by these two notes doesn’t preclude either scenario.

Surely other duplicate Original Series plates were required. The fact that we haven’t spotted them

among the proofs hints that when duplicates were required, they were faithfully copied in every detail down

to the plate letters. That was standard practice when making duplicate plates within the bank note industry

at the time.

Act Approval Dates

The topic of the act approval dates requires development. The earliest national banks were

organized under an act passed February 25, 1863. That entire law was rewritten to eliminate deficiencies

and the revision passed June 3, 1864.

Table 1 reveals that the first bank chartered after June 3, 1864, was The First National Bank of

Figure 19. Only two duplicate Original Series plates have been documented. This note from one was discovered

because they placed 2s below the right plate letters. Heritage Auction Archives photo.

Figure 20. As soon as the Act of June 3, 1864 passed, they started putting the 1864 act approval dates on face

plates for new banks even if they were organized under the 1863 act.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

98

Racine, Wisconsin (457). The Racine bank and all that followed got notes with 1864 act approval dates.

This seems cut and dried, and of little consequence.

However, there is a technicality here. The following are the charter numbers for the banks organized

under the 1863 act: 1-473, 477, 479, 482, 485, 487-489, 491-494, 500, 502, 521, 548 and 555. The skips in

the numbers were caused by delays between the dates the banks were organized and when they were

chartered. The intervening numbers were those for banks organized under the 1864 act that perfected their

charters before the last of the 1863 banks. The salient fact is that the plates for 34 banks with charter

numbers from 457 and above, including the Racine bank, were organized under the 1863 act, but they

received notes bearing the 1864 act date.

Conversely, through quirks of fate that will be chronicled, some plates for banks organized under

the 1864 act ended up with 1863 act approval dates.

All of these situations appear to be technical errors. However, in the eyes of the Treasury officials,

the disconnect between the acts under which the banks were organized and the act approval dates on their

notes was of no consequence so no attention was paid to it. Act dates were not altered on $5 Original Series

or Series of 1875 plates after they were made to bring them into conformity with the laws under which the

banks were organized.

Exotic Situations on $5 Original Series Notes

The Second National Bank of Havana, New York, charter 343, underwent a title change to The

Havana National Bank in 1874. Highly unusual was that the old title was simply removed from their 5-5-

5-5 plate and the new rolled in. The alterations included updating the Treasury signatures and plate date,

but the old variety 2 vignettes and 1863 act date were left as was.

The 5-5-5-5 plate for The Richmond National Bank, Indiana, charter 1102, was recycled for use by

its reorganized successor with the identical title but new charter 2090. The Treasury signatures and plate

date were updated, but the 1863 act date was left as was even though charter 2090 was organized under the

1864 act.

PROTOCOLS INVOLVING SERIES OF 1875 FACE PLATES

All Series of 1875 5-5-5-5 plates made by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing carried variety 4

vignettes and 1864 act dates. This includes plates for all new banks having charter numbers 2282 through

2767. It also includes all title change plates and duplicate plates regardless of charter number.

The Treasury signatures on all Original Series plates that were altered into Series of 1875 forms

were updated to the officers who were current at the time the plates were altered. The plate dates were left

as found. Also, the act approval dates were left as was so old 1863 act approval dates survived on the plates

that carried them. The existing vignettes also were left alone unless they exhibited wear and had to be

reentered. A “printed at” BEP medallion was placed above the title blocks.

When the vignettes on the altered Original Series plates required reentry—either at the time they

were altered into 1875 forms or later—variety 2 and 4 vignettes were used to match those on the plates.

However, all variety 3 vignettes were replaced by either variety 2 or 4 vignettes. No variety 1 plates were

reentered by the BEP.

The Treasury signatures on reentered existing Series of 1875 plates—be they previously altered

Original Series Continental Bank Note plates or Series of 1875 BEP plates—were left as was except for

plates reentered in 1878, which were the first plates reentered at the BEP. The signatures in the 1878 cases

were updated to Schofield-Gilfillan if those signatures weren’t already on the plates.

Stars were placed next to the upper right plate letters on the reentered plates from at least April

1878 through April 1896. See Figure 4 for an example.

In the cases of duplicate plates, the Treasury signatures and plate dates were updated prior to at

least early 1881; thereafter, they were copied from the predecessor plate. Some, but not all, Bureau

siderographers copied every detail from the old to the duplicate plates including the act approval date and

bank note company imprint.

The Treasury signatures and plate dates were updated on all title-change plates. An 1864 act

approval date was used on all. Plate lettering restarted at A-B-C-D.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

99

The BEP omitted the bank note company imprints

from all new and many reentered plates from all Series of 1875

and 1882 national bank note plates beginning in February,

1887. The siderographers also periodically went into the plate

inventory and removed the imprints from existing plates as

time permitted thereafter. Precise dating of adoption of this

protocol comes from the certification dates for two Series of

1882 10-10-10-20 plates for new banks; respectively, The

United States National Bank of Atchison, KS (3612), on

January 22, 1887, with an imprint, and The Albany County

National Bank of Laramie, WY (3615), on February 2, 1887,

without.

Exotic Situations on $5 Series of 1875 Proofs

Two Series of 1875 plates that began their lives as

Original Series plates were recycled for use by reorganized successors with the same title. The pairs were

Rondout, New York (34/2493), and Granville, Ohio (388/2496). In these unusual cases, the signatures and

plate dates were updated, but everything else on the plates was left as was including the variety 2 vignettes

and the 1863 act date.

One particularly strange case involved the 5-5-5-5 plate made for The First National Bank of

Rockville, Indiana, charter 63. It started life as an Original Series plate with variety 2 vignettes and 1863

act approval dates. It was altered into a Series of 1875 form at the BEP with customary updates. Next, the

bank was liquidated and reorganized in 1877 as The National Bank of Rockville, which received new

charter number 2361. Instead of making a new plate, the plate for charter 63 was altered by updating the

bank title, Treasury signatures and plate date. The variety 2 vignettes and obsolete 1863 act approval date

survived through all of this!

MISSING ‘r AND ‘t ON REENTERED BEP PLATES

A peculiar minor variety that occurred during the reentry of a few plates was the omission of the ‘r

after Cash and the ‘t after Pres under the blanks for the bank signatures. This has been observed on notes

from reentered $5 Series of 1875 plates from The Central National Bank of the City of New York (376)

and The Second National Bank of Baltimore (414). The ‘r and ‘t are present on the pre-reentry Series of

1875 Smithsonian proofs.

The omitted ‘r and ‘t were replaced in one New York case. The proof made from a reentered $5

Series of 1875 plate for The Third National Bank of the City of New York (87) exhibits the omission.

Figure 21. Series of 1875 proofs from the

same bank with and without the

Continental Bank Note Company imprint.

Figure 22. The ‘r and ‘t were omitted from cash’r and pres’t next to the signature lines when

the Series of 1875 plate for this New York bank was reentered. Note the reentry star next to

the upper plate letter.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

100

However, a note from the first delivery after the reentry has the letters, so the plate was repaired. That

reentry was reported to the Comptroller in a letter dated November 4, 1879.

The same omissions occur on the $5 Original and 1875 series notes from The Tenth National Bank

of the City of New York (307), printed from the duplicate plate bearing the 2 under the plate letters. See

Figure 19.

FACE PLATE MANUFACTURING AND REENTRY

Central to the production of plates at the Continental Bank Note Company was the use of full-face

generic master dies, of which there were four. The rolls lifted from them were used to lay their images onto

the production plates. The same full-face rolls were used to reenter vignettes on worn plates because the

close tolerances between the interwoven design elements on the $5s precluded the use of separate vignette

rolls for refurbishing the vignettes as was the practice on the higher denomination subjects in the series.

One mistake they made at the Continental Bank Note Company was to engrave the Treasury

signatures on their master dies. Once hardened, those signatures were there to stay. See Figures 2 and 3.

When Register of the Treasury Colby took office on August 11, 1864, variety 3 plates were current.

The protocol was for banks chartered thereafter to carry his signature instead of Chittenden’s. Chittenden’s

signature could not be removed from the variety 3 master full-face die because it had been hardened. The

most likely way the dilemma was solved was to lift a new roll from the die and remove his signature from

the roll. The unwanted signature stood in relief on its surface so it would have been a fairly easy task to

remove it prior to hardening the roll. The only onerous part of the job was clearing the loops in his signature

that extended upward into “with the U. S. Treasury at Washington.” Vestiges of those loops show on some

notes and proofs. See Figure 23.

Colby’s signature then had to be laid-in as a separate operation on each subject along with the bank-

specific items. Therefore, his signature wanders within the space allotted for it from proof to proof and even

between the subjects on the same proof

revealing this is how it was handled.

The change of the act date on the

variety 2 die for charters 457, 458 and

459(?) probably was handled similarly.

Notice from Figure 3 that

Colby’s and Spinner’s signatures were on

the variety 4 master die. Consequently,

when Jeffries and Allison assumed the

office of register on October 5, 1867, and

April 3, 1869, respectively; their

signatures had to be dealt with in the

same fashion as Colby’s had been with

the variety 3 die.

Interesting is that Colby’s

signature on variety 3 faces is slightly

different than on variety 4. The most

easily discernible differences involve

variations between the small loop in the

left side of the “o” and the space inside

the loop of the “l.”

Where the story gets interesting

and a bit convoluted is when the dies,

rolls and plates for the faces were turned

over to the Bureau of Engraving and

Printing in 1875. The Bureau received

the variety 2 and 4 master dies, which

respectively carried Chittenden/Spinner

Figure 23. Colby’s signature (top) was updated on Original Series

plates that were altered into Series of 1875 forms at the BEP.

Notice the residual loop from his signature on the Series of 1875

plate (bottom) for The Market National Bank of Boston (505).

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

101

and Colby/Spinner signatures. Before the Bureau could begin making their own Series of 1875 plates, they

had to contend with those obsolete signatures identically as the Continental Bank Note Company had in the

past. The Bureau employees probably also removed the signatures from the rolls they made from the variety

2 and 4 master dies in order to accomplish the job.

The Original Series plates transferred to the Bureau made for a huge headache because they had to

be altered by updating the Treasury signatures. Those signatures had to be physically removed from each

subject on the plates and the new signatures rolled in. The difficult task was to remove the loops from the

old signatures where they overlapped other design elements. It is not uncommon to find vestiges of those

loops on Series of 1875 notes. See Figure 23.

National bank note face plates were not hardened because production from them was modest.

Consequently, signature and other alterations could be carried out fairly readily. Also, because they were

soft, the plates could be reentered to refurbished worn design elements when necessary.

The lives of plates commonly were prolonged by reentering the vignettes because the vignettes

were the first design elements to exhibit wear. The reentries of $5 Series of 1875 face plates were

accomplished on transfer presses using a full-face roll to repress the parts of the faces containing the

vignettes into the worn plate.

Care was taken by Bureau siderographers to use the appropriate bank note company rolls when

reentering the vignettes on the former Continental Bank Note Company plates. It is clear, however, that

neither the variety 3 master die nor roll(s) lifted from it were transferred to the BEP, or if they were, they

Figure 24. Variety 4 vignettes (bottom note) were reentered over variety 3 vignettes (top note)

when the Series of 1875 plate for this bank was reentered. Faint remnants of the variety 3

tree remain to the left of the upper right counter. Notice that the Treasury signatures were

updated.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

102

were unserviceable because BEP siderographers never reentered a variety 3 vignette on any variety 3 plate

that the Bureau received. When variety 3 plates required reentry, variety 2 or 4 rolls had to be used, thereby

creating interesting and exotic notes. The force exerted through a roll was sufficient to obliterated the old

variety 3 vignettes as the new were laid in over it.

An excellent example involves the issues from The Continental National Bank of Boston,

Massachusetts (524). There are two 5-5-5-5 Series of 1875 proofs in the Smithsonian holdings. As

illustrated on Figure 24, the earlier has variety 3 vignettes, Allison-New signatures and plate letters A-B-

C-D. The later has variety 4 vignettes, Scofield-Gilfillan signatures and plate letters A-B-C-D. Remnants

of the larger left side and top of the variety 3 tree are preserved in the right-hand vignettes on the second

proof. Clearly the plate had been reentered with a variety 4 roll that almost completely obliterated the pre-

existing variety 3 images. The later proof did not have the characteristic stars next to the plate letters,

indicating that the plate was reentered before the Bureau started using stars to designate reentered plates.

A similar observation involves two Series of 1875 5-5-5-5 proofs for The North National Bank of

Boston, Massachusetts (525). In this case, the proof from the reentered plate carries the same Allison-New

signatures as the original, has the reentry stars next to the plate letters and exhibits remnants of the

obliterated variety 3 vignettes. However, it has variety 2 vignettes. See Figure 25. This reentry occurred

later than that for charter 524, after they stopped updating the Treasury signatures. The reentry was reported

to the Comptroller in a letter dated May 2, 1879.

Part IV

THE CONTINENTAL BANK NOTE COMPANY

The Continental Bank Note Company was founded in January,1863 by Waterman Lily Ormsby in

league with financial backers as a rival to the American and National Bank Note companies (McCabe,

2016, p. 124-131). Ormsby was a brilliant individual, albeit very critical of and abrasive to the established

securities engraving profession. He was a skilled engraver, siderographer and mechanical innovator who

improved on machines used in the engraving trade such as the transfer press, geometric lathe, ruling

machine and pantograph. He invented a machine he called the kaleidograph for creating so-called mosaic

engravings along the lines of geometric lathes (Jackson, 1983).

Ormsby stanchly advocated for the adoption by the securities engraving profession of what he

called unit systems for currency designs (Ormsby, 1852, 1862). His unit system involved one picture

engraving covering the entire face of a note with the necessary hand-engraved text interwoven into it “so

that counterfeiters cannot divide it, and procure the parts engraved by professional artists” (Jackson, 1978).

Figure 25. Variety 2 vignettes were reentered over variety 3 vignettes when the plate

containing this note was reentered in May 1879. The Treasury signatures were not changed

because this reentry occurred after they stopped updating signatures on reentered plates.

Notice the star next to the upper left plate letter to signify that the plate had been reentered.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

103

Figure 26. Ormsby’s Original Series $5 design didn’t quite adhere to his unit system design concept (top). The

BEP, with George Casilear as chief engraver, went the opposite direction from Ormsby through the 1870s and

early 1880s with patchwork designs right down to the laying-in of individual letters (middle), but eventually

Treasury officials had second thoughts. Ormsby had been dead for 13 years when the educational silver

certificates hit the streets, which were the embodiment of his unit system concept with lavish engravings that

covered the whole with interwoven hand-engraved text (bottom). Heritage Auction Archives photos.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

104

He touted his concept of unit systems as far superior to the then industry standard patch work

designs that stitched together separate—often stock—vignettes, lathe work and lettering to create the faces

of notes. Early in his career, he distained the use of lathe work—engravings made by geometric lathes—

which were popular and cheap to make that were used as stand-alone ornaments, backgrounds upon which

counters were superimposed and building blocks used in repetitive border work. Naturally, his opinions

drew the ire of his competitors.

Ormsby’s Continental Bank Note Company won the contract for the Original Series $5s. The

design of the faces of the $5s represented a compromise to his unit system principals, yet it stands out in

the Original/1875 series for having more surface area devoted to vignettes than the other denominations.

Although Ormsby organized the Continental Bank Note Company, he didn’t own a controlling

interest. A man named Touro Robertson gained control and pushed him out in 1867. Ormsby attempted to

form a new firm he called Republican Unit Bank Note Company around 1870, but nothing came of it. He

died in 1883, at age 73. The Continental Bank Note Company was merged into The American Bank Note

Company along with the National Bank Note Company in 1879.

Ormsby’s unit note concept was ignored, especially at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing during

Chief Engraver George Casilear’s reign from the mid-1870s to mid-1880s. Casilear’s emphasis was on

lettering and text-dominated designs in a form of patch work that utilized recycled alphabets of engraved

letters that were laid in by siderographers one letter at a time rather than featuring hand engravings. His

designs were attacked as inferior and reviled as inartistic by the engraving establishment.

Eventually the Treasury and Bureau of Engraving and Printing reacted by reviving emphasis on

engraved work, which became ever more elaborate going into the 1890s. The all-time culmination of this

swing was the Series of 1896 educational silver certificates, where no paper could be seen through the

lavish intaglio engravings that covered the notes, and where lettering and counters were almost lost in the

cacophony. Although Ormsby was dead by then, his philosophy behind bank note design had ultimately

infected the BEP.

His post-mortem influence lasted only a few years. By 1899, the Educational Series was supplanted

by more open and streamlined designs. More paper showed through so holders could see the imbedded

threads in the paper, which also were being touted as a counterfeiting deterrent.

CLOSING REMARKS

Four pairs of face vignettes, three back vignettes and three renderings of the use and counterfeit

statements on the backs were used on $5 Original Series and Series of 1875 notes over the 40-year life of

the combined series. Dies and rolls for all of these varieties had been put into service by October 1864.

The use of the retired vignettes on the face plates that they graced lived on, many for a full 20 years

into 1884, when the last of the user banks was extended. In contrast, the lives of the earliest of the back-

vignette plates with 1863 act dates were considerably shorter because none were turned over to the Bureau

of Engraving and Printing for use in printing Series of 1875 notes.

A design feature unique to the $5 denomination in the Original/1875 series was the display of the

act date that authorized the series in the bottom border of the faces and in the counterfeit statement inside

the right back border. Two different act dates appeared, February 25, 1863 and June 3, 1864. The 1864 act

date began service on both the faces and backs as soon as the act was passed regardless of the act that the

bank was organized under. From about July 1871, the 1863 act dates on the faces were mated with 1864

backs. Treasury officials overseeing the note emissions thought nothing of the mis-mating because in their

view the 1864 act simply supplanted the 1863 act wherein the terms governing the issuance and backing

for the notes was the same.

It is unknown which pairs of face vignettes were used on the $5s for charters 459, 526 and 527.

Specimens have not been observed from these banks and proofs for them don’t exist in the Smithsonian

holdings. If you examine the changeover breaks on Table 1, you will observe that the plates for these banks

straddled two of them, thus making discovery of specimens from these three of particular interest to the

authors.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2022 * Whole Number 338

105

REFERENCE CITED AND SOURCES OF DATA

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 1875-1929, Certified proofs of national bank note face and back plates: National Numismatic

Collections, Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, various dates-a, Correspondence to and from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing: Record

Group 318, U. S. National Archives, College Park, MD.

Dillistin, William H., 1956, A descriptive history of national bank notes 1863-1935: Private Printing, Paterson, NJ, 55 p.

Graves, E. O., Edward Wolcott and E. R. Chapman, 1877, Report on the Bureau of Engraving and Printing made by the Committee

of Investigation appointed by the Secretary of the Treasury: Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 40 p. plus

appendices.

Hessler, Gene, 2004, U. S. essay, proof and specimen notes, second edition: BNR Press, Portage, OH, 262 p.

Hessler, Gene, and Carlson Chambliss, 2006. The comprehensive catalog of U. S. paper money, seventh edition: BNR Press,

Portage, OH, 672 p.

Huntoon, Peter, May 2019, Discovery of a new numbered Orig/1875 plate: Bank Note Reporter, v. 68, no. 5, p. 12, 14, 16, 18.

Jackson, Glenn E., 1978, W. L. Ormsby correspondence with Treasury Department uncovered: The Essay-Proof Journal, whole

no. 139, p. 111-118.

Jackson, Glenn E., 1983, Mosaic engraving: The Essay-Proof Journal, whole no. 159, p. 136-138.

Jackson, Glenn E., 1984, Further light on the reputation of W. L. Ormsby, 19th century bank note and stamp engraver: The Essay-

Proof Journal, whole no. 162, p. 60-65.

McCabe, Bob, 2016, Counterfeiting and technology: Whitman Publishing, LLC, Atlanta, GA, 480 p.

Ormsby, Waterman Lily, 1852, A description of the present system of bank note engraving, showing its tendency to facilitate

counterfeiting to which is added a new method of constructing bank notes to prevent forgery: privately published, New

York, NY, 101 p.

Ormsby, Waterman Lily, 1862, Cycloidal configurations or the harvest of counterfeiters, containing matter of the highest

importance concerning paper money, also explaining the Unit System of bank note engraving: privately published, New

York, NY, 45 p.

United States Statutes, March 3, 1875, An act making appropriations for sundry expenses of the government for the fiscal year

ending June 30, 1876: Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Walcutt, Doug, 1996a, Varieties of national bank notes, part five; The Rag Picker (Paper Money Collectors of Michigan): v. 31,

no. 1, p. 12-25.

Walcutt, Doug, 1996b, Varieties of national bank notes, part six; The Rag Picker (Paper Money Collectors of Michigan): v. 31, no.

2, p. 7-16.

Another loss for the Hobby

Sadly, we must report the loss another hobby giant. Roger Durand passed away Feb 6.

Roger was a long-time SPMC member. He joined the society in 1970 as member #2816

and was awarded honorary life member #21. In 2016, he was named to the SPMC Hall