Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

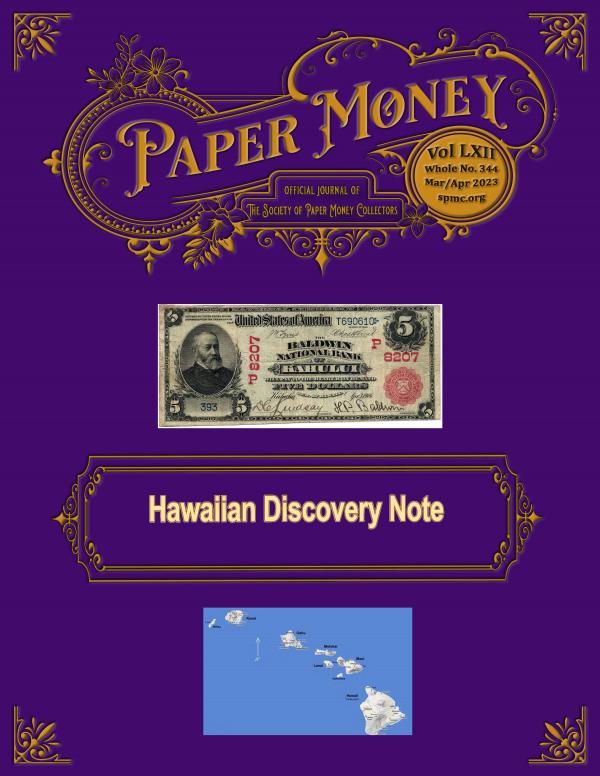

Hawaiian Discovery Note—Peter Huntoon

Merchant Notes of Tuscaloosa Alabama--Charles Derby

Legal Tender Non-Star Serial Ranges--Peter Huntoon

Clayton Cowgill--Terry Bryan

Asachel Eaton's Patents--Tony Chibbaro

Anatomy of a Confederate Note--Steve Feller

Troy Insurance Company--Bill Gunther

Raised Bank Notes of the Pratt Bank--Bernhard Wilde

Collecting UNESCO Notes--Roland Rollins

Follow-up To A 131-Year-Old Mystery--Kent Halland and Charles Surasky

official journal of

The Society of Paper Money Collectors

Hawaian Discovery Note

America’s Oldest and Most Accomplished Rare Coin Auctioneer

1550 Scenic Avenue, Suite 150, Costa Mesa, CA 92626 • 949.253.0916

470 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10022 • 212.582.2580 • NYC@stacksbowers.com

84 State Street, Boston, MA 02109 • 617.843.8343 • Boston@StacksBowers.com

1735 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19103 • 267.609.1804 • Philly@StacksBowers.com

Info@StacksBowers.com • StacksBowers.com

California • New York • Boston • Philadelphia • New Hampshire • Oklahoma

Hong Kong • Paris • Vancouver

SBG PM MidContinent Spring2023 230301

LEGENDARY COLLECTIONS | LEGENDARY RESULTS | A LEGENDARY AUCTION FIRM

Contact Us For

More Information Today!

West Coast: 800.458.4646

East Coast: 800.566.2580

Info@StacksBowers.com

The Mid-Continent Collection

of United States Currency

Featured in the Official

Auction of the 2023

Whitman Coin &

Collectibles Spring Expo

March 21-24, 2023

Additional Highlights from our Spring 2023 Showcase Auction Include:

Fr. 1850-JH. 1929 $5 Federal Reserve Bank Star Note.

Kansas City. PMG Gem Uncirculated 66 EPQ.

Fr. 2400H. 1928 $10 Gold Certificate Star Note.

PCGS Banknote Gem Uncirculated 65 PPQ.

Fr. 2405. 1928 $100 Gold Certificate.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 66 EPQ.

Fr. 609. Escondido, California. $5 1902 Plain Back.

The First NB. Charter #13029.

PCGS Banknote About Uncirculated 55. Serial Number 1.

Fr. 2. 1861 $5 Demand Note.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Fr. 2407. 1928 $500 Gold Certificate.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Fr. 2408. 1928 $1000 Gold Certificate.

PCGS Currency Gem New 65 PPQ.

Fr. 2402H. 1928 $20 Gold Certificate Star Note.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Fr. 2404H. 1928 50 Gold Certificate Star Note.

PCGS Currency Gem New 65 PPQ.

Fr. 2201-A. 1934 Dark Green Seal $500

Federal Reserve Note. Boston.

PCGS Banknote Superb Gem Uncirculated 68 PPQ.

Fr. 2211-CdgsmH. 1934 Dark Green Seal $1000

Federal Reserve Mule Star Note. Philadelphia.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Fr. 1860-AH. 1929 $10 Federal Reserve Bank Star Note.

Boston. PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Fr. 1700. 1933 $10 Silver Certificate.

PCGS Banknote Superb Gem Uncirculated 67 PPQ.

Low Serial Number.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

79

84 Hawaiian Discovery Note--Peter Huntoon

94 Merchant Notes of Tuscaloosa Alabama--Charles Derby

100 L egalT ender Non-Star Serial Ranges--Peter Huntoon

112 Clayton Cowgill--Terry Bryan

115 Asachel Eaton's Patents--Tony Chibbaro

118 anatomy of a Confederate Note--Steve Feller

124 Troy Insurance Company--Bill Gunther

129 Raised Bank Notes of the Pratt Bank--Bernhard Wilde

134 Collecting UNESCO Notes--Roland Rollins

142 Follow-up To A 131-y.o. Mystery--Kent Halland & Charles Surasky

Columns

Advertisers

SPMC Hall of Fame

The SPMC Hall of Fame recognizes and honors those individuals who

have made a lasting contribution to the society over the span of many years.

Charles Affleck

Walter Allan

Doug Ball

Hank Bieciuk

Joseph Boling

F.C.C. Boyd

Michael Crabb

Forrest Daniel

Martin Delger

William Donlon

Roger Durand

C. John Ferreri

Milt Friedberg

Robert Friedberg

Len Glazer

Nathan Gold

Nathan Goldstein

James Haxby

John Herzog

Gene Hessler

John Hickman

William Higgins

Ruth Hill

Peter Huntoon

Glenn Jackson

Don Kelly

Lyn Knight

Chet Krause

Allen Mincho

Clifford Mishler

Barbara Mueller

Judith Murphy

Dean Oakes

Chuck O’Donnell

Roy Pennell

Albert Pick

Fred Reed

Matt Rothert

John Rowe III

Herb & Martha

Schingoethe

Hugh Shull

Glenn Smedley

Raphael Thian

Daniel Valentine

Louis Van Belkum

George Wait

D.C. Wismer

From Your President

Editor Sez

New Members

Small Notes

Uncoupled

Cherry Picker Corner

Obsolete Corner

Quartermaster

Chump Change

Robert Vandevender 81

Benny Bolin 82

Frank Clark 83

Jamie Yakes & Peter Huntoon 136

Joe Boling & Fred Schwan 144

Robert Calderman 152

Robert Gill 155

Michael McNeil 160

Loren Gatch 162

Stacks Bowers Galleries IFC

Pierre Fricke 79

ANA 92

PCGS-C 93

Kagins 111

Tony Chibbaro 117

Benny Bolin 117

Lyn Knight 123

Higgins Museum 133

DBR Currency 133

FCCB 135

Fred Bart 135

Tom Denly 150

MPC Book 151

Bob Laub 156

PCDA 163

Heritage Auctions OBC

Fred Schwan

Neil Shafer

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

80

Officers & Appointees

ELECTED OFFICERS

PRESIDENT

rvpaperman@aol.com

VICE-PRES/SEC'Y Robert Calderman

gacoins@earthlink.net

TREASURER Robert Moon

robertmoon@aol.com

BOARD OF GOVERNORS

Mark Anderson mbamba@aol.com

Robert Calderman gacoins@earthlink.net

Gary Dobbins g.dobbins@sbcglobal.net

Matt Draiss stockpicker12@aol.com

Mark Drengson markd@step1software.com

Pierre Fricke aaaaaaaaaaaapierrefricke@buyvintagemoney.com

Loren Gatch lgatch@uco.edu

William Litt Billlitt@aol.com

J. Fred Maples

Cody Regennitter cody.regennitter@gmail.com

Wendell Wolka

APPOINTEES

PUBLISHER-E

Benny Bolin smcbb@sbcglobal.net

ADVERTISING MANAGER

Wendell Wolka purduenut@aol.com

Megan Reginnitter mreginnitter@iowafirm.com

LIBRAIAN

Jeff Brueggema

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

Frank Clark frank_clark@yahoo.com

IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT

Shawn Hewitt

WISMER BOOk PROJECT COORDINATOR

Pierre Fricke

From Your President

Robert Vandevender IIFrom Your President

Shawn Hewitt

Paper Money * July/August 2020

6

jeff@actioncurrency.com

maplesf@comcast.net

purduenut@aol.com

LEGAL COUNSEL

n

Greetings: Robert Vandevender II In January, we held our first annual SPMC general membership and breakfast

meetings at the FUN show and by most accounts, everything went well. We are

looking forward to doing it again next year. For those of you who could not

attend, we had plenty of staff and traffic at the SPMC table with every chair filled

at numerous times. We also had displayed a framed memorial with flowers

recognizing the passing of twelve of our members and significant numismatic

contributors over the past couple of years. This year, we participated in the youth

scavenger hunt with a question to ask each of the kids who came by the table and

after answering, we awarded them with a free foreign banknote. The question we

asked this year is what a star means as a part of the US currency serial number.

We had such a strong turnout of kids stopping by we ran out of Venezuelan

notes to hand out and had to hit the floor to purchase some Peru notes for the

table. We were pleased to meet with both the Ben Franklin and Abraham Lincoln

actors and gave them each SPMC advertising flyers fashioned as currency from

their time period to hand out to people who visited their table. They ran out of

flyers very quickly and we are making plans to have more printed for their use.

On Thursday morning we held a general membership meeting with light

attendance. Several of the people who did attend had various currency items with

them. We all took turns playing show-and-tell with the items we had available.

Next year, we will look to schedule the meeting at a better time when more

people will be available to attend.

The breakfast on Saturday was attended by the maximum crowd for which we

had planned this year and was well received. The room at the convention center

was perfect for acoustics and there was plenty of food at the buffet. Abraham

Lincoln even made an appearance at the start of the breakfast. This year, the

Tom Bains raffle, conducted by our favorite ticket puller, Wendell Wolka,

included a nice final prize worth an estimated $750. For next year, we are

considering expanding the allowed attendance above the 60 we had chosen for

this year.

With this being the first annual meeting we have held since the Covid event

started a couple of years ago, and the first at the FUN show location, we learned a

few things and are planning some improvements for next year.

In February, Vice President Robert Calderman and I attended the Long Beach

Expo. SPMC member, Nancy Purington and I staffed the SPMC table while Mr.

VP Calderman was busy horse trading at Jim Fitzgerald’s table. Everyone

seemed to have a good time. The Long Beach Expo is rapidly becoming my

favorite show to attend. The staff are easy to work with, they give out fantastic

door prizes, and the public traffic is heavy. At the SPMC table we gave out many

applications and did welcome two new members at this show and hope a few of

the handed-out applications come in later. We are already booked to staff the

SPMC table at the June Long Beach show. Please stop by and say hello if you

are in the area.

81

Terms and Conditions

The Society of Paper Money Collectors (SPMC) P.O. Box 7055,

Gainesville, GA 30504, publishes PAPER MONEY (USPS 00‐

3162) every other month beginning in January. Periodical

postage is paid at Hanover, PA. Postmaster send address

changes to Secretary Robert Calderman, Box 7055, Gainesville,

GA 30504. ©Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc. 2020. All

rights reserved. Reproduction of any article in whole or part

without written approval is prohibited. Individual copies of this

issue of PAPER MONEY are available from the secretary for $8

postpaid. Send changes of address, inquiries concerning non ‐

delivery and requests for additional copies of this issue to

the secretary.

MANUSCRIPTS

Manuscripts not under consideration elsewhere and

publications for review should be sent to the editor. Accepted

manuscripts will be published as soon as possible, however

publication in a specific issue cannot be guaranteed. Opinions

expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect those of the

SPMC. Manuscripts should be submitted in WORD format via

email (smcbb@sbcglobal.net) or by sending memory stick/disk

to the editor. Scans should be grayscale or color JPEGs at

300 dpi. Color illustrations may be changed to grayscale at the

discretion of the editor. Do not send items of value.

Manuscripts are submitted with copyright release of the author

to the editor for duplication and printing as needed.

ADVERTISING

All advertising on space available basis. Copy/correspondence

should be sent to editor.

All advertising is pay in advance. Ads are on a “good faith”

basis. Terms are “Until Forbid.”

Ads are Run of Press (ROP) unless accepted on a premium

contract basis. Limited premium space/rates available.

To keep rates to a minimum, all advertising must be prepaid

according to the schedule below. In exceptional cases where

special artwork or additional production is required, the

advertiser will be notified and billed accordingly. Rates are

not commissionable; proofs are not supplied. SPMC does not

endorse any company, dealer, or auction house. Advertising

Deadline: Subject to space availability, copy must be received

by the editor no later than the first day of the month

preceding the cover date of the issue (i.e. Feb. 1 for the

March/April issue). Camera‐ready art or electronic ads in pdf

format are required.

ADVERTISING RATES

Editor Sez

Benny Bolin

Required file submission format is composite PDF v1.3

(Acrobat 4.0 compatible). If possible, submitted files should

conform to ISO 15930‐1: 2001 PDF/X‐1a file format standard.

Non‐ standard, application, or native file formats are not

acceptable. Page size: must conform to specified publication

trim size. Page bleed: must extend minimum 1/8” beyond

trim for page head, foot, and front. Safety margin: type and

other non‐bleed content must clear trim by minimum 1/2”.

Advertising c o p y shall be restricted to paper currency, allied

numismatic material, publications, and related accessories.

The SPMC does not guarantee advertisements, but accepts

copy in good faith, reserving the right to reject objectionable

or inappropriate material or edit copy. The SPMC

assumes no financial responsibility for typographical

errors in ads but agrees to reprint that portion of an ad in

which a typographical error occurs.

Benny

Space

Full color covers

1 Time

$1500

3 Times

$2600

6 Times

$4900

B&W covers 500 1400 2500

Full page color 500 1500 3000

Full page B&W 360 1000 1800

Half‐page B&W 180 500 900

Quarter‐page B&W 90 250 450

Eighth‐page B&W 45 125 225

I hope all who attended FUN this past January had a good

time. I know I did. I was worried about getting to the show and

then back home as I was flying Southwest Airlines! And I had to

leave Kim home by herself only five weeks after her second

knee replacement in three months. But, I was only gone for two

nights and all went well. Kim care for herself really well and

there were no travel mishaps. I only bought two manuscript

fractionals but I had a blast visiting with other members and

collectors, seeing the exhibits and meeting the daughter of

astronaut Alan Shepard's daughter, Laura who, like her father is

an astronaut. She helped man the Astronauts Memorial Fund

booth on the bourse. I really enjoy anything about space and

remember watching Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin step on the

moon in July, 1969. It was exciting. I also collected first day

covers of all the space shuttle mission. At the AMF booth I got

one of the new collectible notes they have made that has a serial

number in a format styled after NASA Kennedy's iconic

countdown clock. In a pure stroke of luck, mine showed the

number 10:22--my birthday! We also had a good time at the

SPMC breakfast and Tom Bain raffle, two items we hope to

duplicate next year. The souvenir ticket honored Neil Shafer on

the front and we were fortunate enough to have the designer,

engraver and printer of the note, Tom Stebbins and his wife

Summer present.

It seems the market is hopping and active. I don't go to

many shows, but reports are that collectors are out in force once

again.

Hope that all of you have weathered this crazy weather and

found hobby related things to keep you busy indoors. Maybe

you have written an article for Paper Money? Even with the

weird weather in Texas, ice shuts us down one week, then a

week of tropical temps, then shut down the next week for ice

again, it appears that the outlook for a hobby friendly spring and

summer is bright and sunny.

Since I have been spending time after FUN playing nurse to

my wife and at school, I have not had a lot of time to do paper

activities. But--the future looks good. I hope to be able to get

out to a few shows this spring and summer and I have a couple

of ideas for articles to write. All in all, I hope to keep busy and

hope you will do the same. As alwasys, I am asking you to

hunker down and write me an article.

82

The Society of Paper Money

Collectors was organized in 1961 and

incorporated in 1964 as a non-profit

organization under the laws of the

District of Columbia. It is

affiliated with the ANA. The

Annual Meeting of the SPMC is

held in June at the International

Paper Money Show. Information

about the SPMC, including the

by-laws and activities can be

found at our website--

www.spmc.org. The SPMC does

not does not endorse any dealer,

company or auction house.

MEMBERSHIP—REGULAR and

LIFE. Applicants must be at least 18

years of age and of good moral

character. Members of the ANA or

other recognized numismatic

societies are eligible for membership.

Other applicants should be sponsored

by an SPMC member or provide

suitable references.

MEMBERSHIP—JUNIOR.

Applicants for Junior membership

must be from 12 to 17 years of age

and of good moral character. A parent

or guardian must sign their

application. Junior membership

numbers will be preceded by the letter

“j” which will be removed upon

notification to the secretary that the

member has reached 18 years of age.

Junior members are not eligible to

hold office or vote.

DUES—Annual dues are $39. Dues

for members in Canada and Mexico

are $45. Dues for members in all

other countries are $60. Life

membership—payable in installments

within one year is $800 for U.S.; $900

for Canada and Mexico and $1000

for all other countries. The Society

no longer issues annual membership

cards but paid up members may

request one from the membership

director with an SASE.

Memberships for all members who

joined the Society prior to January

2010 are on a calendar year basis

with renewals due each December.

Memberships for those who joined

since January 2010 are on an annual

basis beginning and ending the

month joined. All renewals are due

before the expiration date, which can

be found on the label of Paper

Money. Renewals may be done via

the Society website www.spmc.org

or by check/money order sent to the

secretary.

WELCOME TO OUR

NEW MEMBERS!

BY FRANK CLARK

SPMC MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

Dues Remittal Process

Send dues

directly to

Robert Moon--SPMC Treasurer

104

Chipping Ct Greenwood, SC 29649

Refer to your

mailing label for when your

dues are due.

You may also pay your dues online at

www.spmc.org.

NEW MEMBERS Jan/Feb 2022

15513 Patrick Ferrell, Website

15514 Genatius Ray, Blackbook

15515 Adam Osborne, Steve Litchfield

15516 James R. Rundquist, Website

15517 George Turner, Frank Clark

15518 Jeffrey Cosello, Website

15519 Jonathan Lindley,

15520 Konrad Juengling, Website

15521 Austin Neita, Robert Calderman

15522 Mark Wretschko, Webs

15523 Greg Bennick, Kent Halland

15524 Dewey Bolton, Website

15525 Robert Green, Website

15526 Jay Prestin, Website

15527 Jacob Williamson, Robert Vandevender

15528 Patrick McBride, Robert Vandevender

15529 Gary Greenburg, Robert Calderman

15530 Steve Jinks, Website

15531 Andrew Presswood

15532 Rick Prall, Website

15533 Henry Tyson, Robert Calderman

15534 Patricia Feinberg,

15535 Daniel Jones, Website

15536 David Mullins, Website

15537 Robert Shanks, Robert Vandevender

15538 Aaron Rapaport, Robert Vandevender

15539 Richard Faath, Website

REINSTATEMENTS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

None

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

83

Kahului, Hawaii Territorial

1902 Red Seal

Discovery of the Decade

Drink in this extraordinary find. Yes, it is a 1902 red seal from Hawaii—the first ever reported from

that territory.

Arrival of this Kahului note in Andrew Shiva’s collection represents the last piece in the puzzle

required for someone to assemble a complete collection of red seals from every territory and state.

Not only that, it is the last remaining territorial type to appear. We now have at least one

Original/1875, 1882 brown back, 1882 date back, 1882 value back, 1902 red seal, 1902 date back and 1902

blue seal plain back from every territory in which those types were issued.

A Series of 1902 red seal territorial has been the most anticipated territorial discovery since an 1882

Territory of Alaska brown back arrived a decade ago.

Only two of the four banks from Hawaii that issued notes utilized red seals, The First National

Banks of Lahaina and The Baldwin National Bank of Kahului. Both dribbled them out in small numbers.

Soak up the appearance of this wonderful jewel. It earned its stripes as a piece of currency by

The Paper

Column

Peter Huntoon

Figure 1. The first Series of 1902 red seal reported from Hawaii Territory.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

84

circulating, but miraculously it didn’t sustain any damage along the way.

• The note exhibits even circulation without blemishes of any type on either side.

• The penned bank signatures are absolutely spectacular, perfectly formed, legible and as

bold as the day they were applied.

• The note is well centered.

• The colors—the red seal, the blue serial numbers, the intaglio face and back inks—are

vivid.

Those of us with fingers on the pulse of nationals despaired that any red seals had survived from

Hawaii. After all, it has been over a hundred years since they were current. Their age coupled with small

numbers spoke of high risk.

The Kahului bank had a circulation of only $13,000 during the red seal era and the Lahaina bank

had $6,250. To support those meager circulations, only 3,396 $5, $10 and $20 red seals were issued through

the Kahului bank and 960 $10s and $20s from Lahaina. Don’t forget that these totals take into account worn

notes that were replaced from circulation, so at any one time there were far fewer of them out there in

people’s pockets than these totals suggest.

Table 1 reveals that there were two red seal printings for the Kahului bank. Table 2 shows that the

first shipment to the bank occurred as soon as the Comptroller’s office received the notes from the Bureau

of Engraving and Printing. The shipment to the bank on December 17th, 1908 containing the discovery

note consisted solely of $5 sheets. It probably took weeks for the notes to arrive at the bank.

The signers of the note were president Henry Perrine Baldwin and cashier David Colville Lindsay.

We’ll profile both, but to do so we’ll have to place them in the historical context of early Hawaiian political

and economic history; the stage on which Henry Baldwin was a major player and Lindsay prominent.

This is a story of land, because land was everything at the time, particularly separating the

indigenous Hawaiians from that land. I’ll paint this picture in broad strokes.

This is not original research on my part but rather a synthesis of information gleaned from relevant

web pages listed below that cite the origin of the facts, figures and dates that are presented here.

Our story begins with the arrival of New England missionaries to Hawaii beginning in 1820, one

Table 2. Inclusive dates when Kahului red seal sheets

were shipped from the Comptroller of the Currency's

office in Washington, DC, to the bank.

June 5, 1906-July 15, 1909 5-5-5-5 1-465

June 5, 1906-November 17, 1909 10-10-10-20 1-384

Discovery note on sheet 393 was in this shipment

Dec 17, 1908 5-5-5-5 376-405

Table 1. Deliveries of Kahului red seal 4-subject

sheets from the Bureua of Engraving and Printing

to the Comtproller of the Curency.

First Printing

June 4, 1906 5-5-5-5 1-315 E634579-E634893

June 5, 1906 10-10-10-20 1-264 R69222-R69485

Second Printing

June 23, 1908 5-5-5-5 316-465 T690533-T690682

June 23, 1908 10-10-10-20 265-384 V162002-V162121

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

85

of these being Henry Baldwin’s father, Dwight Baldwin, both a missionary and medical doctor, who arrived

in 1831. What the missionaries found was a native population being decimated by disease, vast tracks of

fertile land much of which was idled by deceased Hawaiians, and a withering native social fabric vulnerable

to predatory outside manipulation.

The problem was that the Hawaiians had lived in isolation for so long before western contact, they

had no immunity to external diseases. Captain James Cook and the crews of his two ships who discovered

the place in January of 1778, left them with gonorrhea, syphilis and likely tuberculosis. Whalers and later

arrivals brought with them epidemics of influenza, cholera, whooping cough, mumps, measles, dysentery.

small pox, leprosy, diphtheria, bubonic plague, scarlet fever, among others, all killers of Hawaiians. Dr.

Dwight Baldwin diagnosed the first case of leprosy on Maui in 1840. It alone killed 4,000 over the next 30

years. Smallpox arrived from California in 1853.

The impact on the native Hawaiian population was stark. Estimates of the pre-contact population

of 1778 range from 120,000 to 600,000. By 1805, it was 150,000 to 200,000, 1819–144,000, 1850–84,165,

1872–56,897, 1890–34,400. 1900–28.800. These figures represent at least a 90 percent die-off by the time

Hawaii became a U.S. territory in 1898.

King Kamehameha I had established the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1810 and his son Kamehameha II

had opened Hawaii to the missionaries in 1820. Under their influence, Kamehameha III had in 1840 adopted

Hawaii’s first constitution, and by 1848 instituted judicial and executive branches of government, as well

as a system of land ownership for the first time. The 1848 land policy divided the Hawaiian lands between

Kamehameha III and 245 chiefs.

Subsequent acts by 1850 allowed both native commoners and foreigners to own land in fee simple.

This was the major event that allowed for the eventual destruction of the Monarchy. Haole entrepreneurs

could now buy up land to set up plantations, legally wresting title to the land permanently from the natives.

Thusly, many children of the missionaries found opportunity far beyond saving souls. There was plenty of

underutilized land ideal for growing crops, especially sugar cane and pineapples.

As the plantation economy took root, one irony was that the native labor force was too depleted to

suffice. The first Chinese laborers arrived in 1852. By the 1880s there were more than 25,000 of them,

equal to half the native population. Japanese laborers began to arrive in 1868 and by 1902 their number was

30,000 working the plantations. Portuguese workers began to arrive in 1877 and their numbers swelled to

15,000 by 1900. Norwegians and Germans also came before the turn of the century, followed by Filipinos

and some Spaniards during the next decade. The native Hawaiians were greatly outnumbered and largely

landless by the start of the 20th century.

The event that launched Hawaii to the forefront of worldwide sugar cane production was the

Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 passed by the U.S. Congress. It provided for duty-free sugar importation to the

United States, a reward for allowing U.S. naval facilities to be built on the islands. The industrialization of

Hawaiian sugar cane production went into high gear and embraced corporate models of scale parallel to

those of the titans of mainland industrialists such as John Rockefeller and his Standard Oil Company.

Serious consolidations of plantations occurred, from 70 to 20 between 1875 and 1883. Capital flowed in to

allow the remaining plantations to expand into marginal lands and to build aqueducts to water them. Vertical

corporate integration models were employed. The growers built their own sugar mills, build vast irrigation

networks to supply their fields, operated transportation systems to move their product, etc. Rockefeller had

nothing on the winners.

Key to their success and power was that they acquired vast tracks of Hawaiian land through

purchases and mergers.

Eventually five Kingdom-era corporations became behemoth conglomerates known as the Big

Five; specifically, Castle & Cooke, Alexander & Baldwin, C. Brewer & Co., American Factors, and Theo

H. Davis & Co. They controlled 90 percent of the international sugar business after annexation of Hawaii

to the United States. However, they weren’t fierce competitors. They had interlocking ownership and

interlocking boards, which colluded to keep the prices of sugar and other services they offered high. Henry

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

86

P. Baldwin emerged as the head of one of them.

Henry Perrine Baldwin

Henry Perrine Baldwin was born August 29, 1842 in

Lahaina on Maui. He attended Punahou School in Honolulu,

then returned to Lahaina.

His family and that of another Lahaina missionary

named William P. Alexander were close so the children were

acquainted from their youths. Upon Henry’s return from

Honolulu, he managed a rice farm owned by Alexander’s

eldest son, but the venture failed. He then worked on his own

eldest brother’s small sugarcane farm.

Henry also had developed a close friendship with one

of the Alexander siblings, Samuel Thomas Alexander born in

1836.

Samuel Alexander returned to Maui after studying on

the mainland and began teaching at Lahainaluna High School

where he and his students successfully grew sugarcane and

bananas. Word of the venture reached the owner of the

Waihee sugar plantation near Wailuku where Alexander was

hired as the plantation manager. He in turn hired Henry as a

foreman. This began a lifelong working partnership between

the two.

Alexander was the idea man, the more outgoing and

adventurous of the two. He had a gift for raising money to

finance his business projects. Baldwin was more reserved and

was considered the doer in the partnership. He carried out the

projects conceived by Alexander.

By 1869, the young men—Alexander 33, Baldwin,

27—launched their own business. Still working at Waihee,

they purchased 12 acres in the Sunnyside area of Makawao

on Maui for $110 to grow sugarcane. The following year,

they bought another 559 acres for $8,000, giving birth to what became Alexander & Baldwin, Inc. Baldwin

married Alexander’s sister Emily in 1870, who was four years younger.

Lightning struck with passage of the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, opening tariff-free sugar trade

with the United States, and they smelled opportunity. Maui consists of two giant volcanos—Haleakala, at

10,023 feet, lies to the east and 5,788-foot Pu’u Kukui to the west—separated by a broad saddle most of

which has an elevation of less than 500 feet covered with soil ideal for sugar plantations. The Alexander-

Baldwin lands were on the east side of this expanse at the foot of Haleakala in the vicinity of Paia. The

issue there was that sugar cane plants are very thirsty but their land was in the rain shadow of Haleakala so

received limited and unreliable rainfall. However, it was endowed with a 12-month growing season.

Alexander envisioned an aqueduct that could bring water from perennial streams flowing off the

windward rainy northeast facing flake of Haleakala. The aqueduct would collect and move the water

westward around the rugged north side of Haleakala to central Maui to irrigate 3,000 acres of their lands as

well as neighboring plantations. Alexander organized the Hamakua Ditch Company in league with other

growers to build the 17-mile aqueduct. That audacious project commenced September 30, 1876.

In the meantime, Baldwin suffered the worst day of his life. On March 28, 1876, he was adjusting

rollers in the cane grinder at the Paliuli Mill when his right hand became entangled in the mechanism,

pulling in his arm. A worker stopped the machine before it killed him and reversed the rollers. Another was

sent 10 miles to fetch the nearest physician who amputated what was left of his arm.

Figure 3 illustrates that he learned to write with his left hand. It is reported that he continued to play

the organ at his church with his left hand and was riding horseback in his fields within a month.

Figure 2. Henry P. Baldwin as a young man.

Wikipedia photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

87

The Hamakua Ditch was completed, over budget, at a cost of $80,000 in 1878. Water started to

flow to the Castle & Cook plantation in July 1877. The last major obstacle, the deep Maliko Gulch, was

crossed later in order to reach the Alexander-Baldwin land.

The crossings of precipitous gulches, some of which were hundreds of feet deep, were

accomplished by use of innovative inverted syphons. Baldwin would lower himself down into the gulches

daily with his remaining arm in order to supervise the work. Tunnels were used to pass the ditch through

obstacles. When completed, the Hamakua Ditch delivered 60 million gallons per day.

The ditch system was greatly expanded over ensuing decades famous for the use of miles of tunnels.

It was copied elsewhere in Hawaii and the American west. The Hamakua Ditch became the nucleus for

their East Maui Irrigation Company, a very profitable subsidiary.

Alexander and Baldwin formalized their partnership in 1883 by incorporating their sugar business

as the Paia Plantation. They served as agents for nearly a dozen plantations over the next 30 years and

greatly expanded their plantation and milling operations.

Sugar King Claus Spreckels bought 40,000 acres on Maui after the Reciprocity Treaty, incorporated

the Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company, and built his own extensive ditch system and a mill at

Spreckelsville. He already monopolized sugar refining on the west coast of the mainland with his California

Sugar Refinery in San Francisco. A measure of his reach was the fact that in 1884 he bought the entire

Hawaiian crop of sugar to refine at his San Francisco plant.

Henry Baldwin and a few businessmen from Honolulu created the Haleakala Ranch with a purchase

of 33,817 acres on the slopes of the volcano in 1888.

Baldwin was elected to the Kingdom House of Nobles where he served from 1887 to 1892. His

service followed the insurrection of 1887 in which then King Kalakaua was forced at gun point to sign a

new constitution written by anti-monarchists. The so-called Bayonet Constitution, written by members of

the Hawaiian League, invested the power of the monarchy in a cabinet controlled by American, European

and Hawaiian elites through restrictive voting rights written into the constitution that disenfranchised

Asians and most Hawaiians. The insurrection was fomented by the Hawaiian League, which was a militant

outgrowth of the Reform Party. Baldwin was a member of the Reform Party, formerly known as the

Missionary Party, which advocated the dissolution of the monarchy and annexation of Hawaii to the United

States. He wasn’t involved in the insurrection because that type of activity simply wasn’t his style.

King Kalakaua died in 1891 and was succeeded by his sister Queen Liliuokalani. The queen

proposed a new constitution to restore the power of the monarchy and extend voting rights for the native

Hawaiians. Hawaii’s white businessmen formed a 13-member Committee of Safety with the goad to

overthrow the monarchy. On January 17, 1893, the committee along with its extra-legal armed militia

assembled near the queen’s palace to initiate the coup. John Stevens, U.S. Minister to Hawaii, summoned

162 U.S. Marines and Navy sailors to protect the committee, The queen surrendered to the committee in

order to avoid violence. The committee then formed a provisional government.

Democratic President Grover Cleveland opposed the provisional government and called for

restoration of the monarchy. Rebuffed, the Committee of Safety established the Republic of Hawaii. Two

years later in 1895, Hawaiian royalists staged a failed coup against the republic and Queen Liliuokalani

was arrested and convicted of treason for her alleged role in the coup. At this point, she formally abdicated

and dissolved the monarchy. Baldwin was elected to the senate of the Republic after her abdication.

Annexation of the Territory of Hawaii to the United States had to await the election of Republican

William McKinley in 1897 who favored annexation. U.S. involvement in the Philippines during the

Spanish-American War of 1898 accentuated the strategic importance of Hawaii. A joint resolution of

Figure 3. Henry Baldwin learned to write with his left hand after losing his arm to a sugar cane grinder in 1876.

From Uota (2016).

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

88

Congress called the Newlands Resolution providing for the

annexation of Hawaii was signed into law July 2, 1898 by

McKinley. Baldwin now found himself serving in the Hawaiian

territorial senate through 1904.

Alexander & Baldwin had outgrown its partnership

organization by the time Hawaii became a U.S. territory so in 1900

they incorporated to increase capitalization and facilitate

expansion. Their Articles of Association were filed with the

treasurer of the Territory of Hawaii on June 30. The principal

office of Alexander & Baldwin, Ltd was in Honolulu with a

branch in San Francisco. The Board of Directors consisted of

Joseph P. Cooke, Wallace M. Alexander, James B. Castle, Henry

Baldwin and Samuel Alexander. Henry Baldwin was named

president.

Two of Spreckels’ sons, who had won ownership of

HC&S in litigation against their father, sold it to Hawaiian sugar

interests in 1898. Alexander and Baldwin owned the controlling

interest. A year later HC&S acquire the narrow gage Kahului

Railroad, which dated from 1879, as well as Maui Railroad &

Steamship and merged the latter into the former. The Kahului

Railroad began development of Kahului Harbor. This marked

Alexander and Baldwin’s expansion into transportation. Baldwin

managed HC&S from 1902 to 1906.

Baldwin bought The Maui News in 1905 and his

descendants continued to own the paper until 2000.

Samuel Alexander was killed in 1904 at the age of 68 in a

freak accident while hiking with his daughter at Victoria Falls,

Africa, where he was struck by a boulder. Baldwin died July 8,

1911, also at age 68 from failing health.

Alexander & Baldwin diversified and remains in business. The partnership, created with the

purchase of 12 acres on Maui for $110, has grown into a holding company with multi-billions in assets. It

owns about 91,000 acres of land in Hawaii so is the fifth-largest landowner in the state.

The greatest challenge came to The Big Five after statehood in 1957 when the U.S. Department of

Justic challenged as monopolistic the ownership of Madson Navigation Company by four of the five

companies. Theo H. Davies didn’t have an interest in Matson. The lawsuit was settled when three of the

four agreed to divest. Alexander and Baldwin bought out those interests, completing the purchase in 1964.

David Colville Lindsay

Mr. Lindsay. Long resident of Maui and one of the its best-known citizens died at Queen’s hospital,

Honolulu, Saturday night.

A retired manager of the former Alexander and Baldwin Paia Plantation Co., Mr. Lindsay was also

the organizer of the Baldwin National Bank on Maui.

He was born in Kirriemuir, Scottland, June 23, 1870.

In 1890 he came to Hawaii and worked for the Paia Plantation Co., and was appointed manager in

1896.

Following reorganization of Baldwin Bank, Ltd., in 1921, he became cashier and general manager.

He became manager in 1906 of the merged organization of the Paia Plantation and the Haiku Sugar

Co. Mr. Lindsay resigned his position in 1925.

After spending several weeks on the mainland, he was recalled to become general manager of the

Maui Electric Co.

Mr. Lindsay became manager of the Haiku Fruit and Packing Co., in January 1926. This firm later

was the Haiku Pineapple Co.

Figure 4 David Colville Lindsay,

cashier, The Baldwin National Bank of

Kahului, Hawaii Territory. Photo from

obituary in findagrave.com.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

89

He was a resident of Niu, Oahu since 1930.

Lindsay died March 6, 1948 at age 77.

Banking on Maui & The Baldwin National Bank

Organizers had two choices when incorporating a bank in the Territory of Hawaii: organize under

territorial banking law or under U.S. national banking law. Territorial banking law was far less restrictive

so those banks could loan on real estate and could have branches. In contrast, national banks were designed

to be commercial banks that made short term loans to businesses and industries except for real estate,

branching was not allowed at the time, and oversight was far more rigorous.

The 1897 Civil Laws for the Hawaiian Islands required banks to have a minimum capital of

$200,000, whereas the minimum capital requirement for a national bank after passage of the Gold Standard

Act of March 14, 1900 was only $25,000 for banks in towns of 3,000 or less, and more for towns with

larger populations. National banks were considered safer, but the ability to loan on land could be more

profitable for a bank operating under territorial law. Only national banks could serve as fiscal agents for the

U.S. Government.

The organic act establishing the Territory of Hawaii was passed by Congress and signed into law

by President McKinley on June 11, 1900. Syndicates of investors had been petitioning the Comptroller of

the Currency to reserve titles for proposed banks there since the overthrow of the monarchy, especially in

Honolulu. The First National Bank of Hawaii at Honolulu was chartered October 17, 1901 with a capital of

$500,000. It flourished over the decades and joined the ranks of the top tier banks in the nation.

However, the First National of Honolulu had major competition from The Bank of Hawaii, which

had been organized in 1893 by Charles M. Cooke following dissolution of the monarchy. His bank obtained

a charter in 1897 from the Republic of Hawaii. Cooke seriously eyed Maui’s developing sugar economy as

fertile ground. In league with First National’s president Cecil Brown and H. P. Baldwin, they sent Charles

D. Lufkin, a teller from First National, over to Maui to begin to organize a chain of national banks. The

idea was to take advantage of the low capitalization requirement for such banks and to keep the Maui

business separated on paper from the Oahu business. The banks Lufkin organized in order of dates of charter

Figure 5. The Baldwin National Bank, Kahului, Hawaii Territory. From Uota, 2016.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

90

were The First National Banks of Waluku

(October 17, 1901), Lahaina (February 19, 1906),

and Paia (September 26, 1913).

Cooke served as president and Lufkin as

cashier in them except briefly for Waluku where

W. J. Lowrie, a board member, served as president

during its first year. Lowrie left to manage a sugar

plantation in Puerto Rico so Cooke took over as

president and David Lindsay, the Alexander &

Baldwin plantation manager, filled Lowrie’s

vacated directorship.

On paper the three national banks were

standalone institutions, but, in the classic chain

banking style of the times, they had interlocking

ownership and directors.

Cooke resigned his presidencies in the

three banks and limited himself to the presidency

in The Bank of Hawaii at Honolulu. This move

complied with Section 8 of the Clayton Antitrust

Act of 1914 prohibiting interlocking directorates

in national banks that went into effect in 1916.

Next the three banks were liquidated May 1, 1917

in order to be reorganized under a territorial

charter as the Bank of Maui. Its main office was at

Waluku; the others became branches. Being a

territorial chartered bank, Cooke assumed the

presidency and all was well. The best part was that

the Bank of Maui could make loans on land and

even seed new branches. It was Maui’s million-

dollar bank.

Henry P. Baldwin, of course, could use a

bank of his own so now that Lindsey knew

something of the banking business, Baldwin had him resign his directorship in The First National Bank of

Waluku in the fall of 1905 so he could organize The Baldwin National Bank in Kahului. The Kahului bank

was chartered May 5, 1906 as the third national bank on Maui.

Baldwin installed his eldest son Henry Alexander Baldwin as its first president for the first year or

so, then Henry P. took over until his death in 1911. Henry A. reassumed the presidency thereafter. Lindsay

served as cashier, which was the operating manager position, for the entire life of the bank.

After observing the more rapid growth of the Bank of Maui, Henry A. Baldwin and the other

directors of the bank decided to jettison its restrictive national charter and reorganize as Baldwin Bank,

Ltd., on January 3, 1921. H. A. Baldwin and D. C. Lindsay retained their roles in the new entity. A

controlling interest in the bank was sold to the Pacific Trust Company in 1924.

One thing about the second-generation missionary children was that in sugar, pineapples,

transportation, banking, whatever, the concept of conflict of interest was unknown. Through interlocking

ownerships and directorships, some became oligarchs whose influence spread well beyond Hawaii. Their

legacy was encapsulated as “The missionaries came to Hawaii to do good; their sons did well.”

Sources

Book: Jeremy Uota, 2016, Hawaii national bank notes: Stuffcyclopedia, Kaneohe, HI, 261 p. is the must-read authority on

Hawaiian national bank notes and bank history. Available from stuffcyclopedia@gmail.com.

http://papaolalokahi.org/images/pdf-files/hawaiian-health-time-line-and-events.pdf

https://alexanderbaldwin.com/about/history/

https://archive.nytimes.com/learning.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/01/17/jan-17-1893-hawaiian-monarchy-overthrown-by-america-

backed-businessmen/

Figure 6. Henry Perrine Baldwin while president of

The Baldwin National Bank of Kahului, Hawaii

Territory. Wikipedia photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

91

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1887_Constitution_of_the_Hawaiian_Kingdom#:~:text=The%201887%20Constitution%20of%20t

he,European%20and%20native%20Hawaiian%20elites.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Hawaiian_population

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bank_of_Hawaii

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Five_(Hawaii)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colonial_epidemic_disease_in_Hawai%27i#Leprosy_(1865-1969)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dwight_Baldwin_(missionary)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Perrine_Baldwin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kahului_Railroad

https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/joint-resolution-for-annexing-the-hawaiian-

islands#:~:text=House%20Joint%20Resolution%20259%2C%2055th,of%20the%20Territory%20of%20Hawaii.

https://www.asce.org/about-civil-engineering/history-and-heritage/historic-landmarks/east%20maui-irrigation-system

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/66306261/david-colville-lindsay

https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entries/claus-spreckels-robber-baron-and-sugar-king/

https://www.mauinews.com/news/local-news/2016/12/the-history-of-hawaiian-commercial-sugar-co/

https://www.usgenwebsites.org/HIHonolulu/history/immigrants.html

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

92

You Collect. We Protect.

Learn more at: www.PCGS.com/Banknote

PCGS.COM | THE STANDARD FOR THE RARE COIN INDUSTRY | FOLLOW @PCGSCOIN | ©2021 PROFESSIONAL COIN GRADING SERVICE | A DIVISION OF COLLECTORS UNIVERSE, INC.

PCGS Banknote

is the premier

third-party

certification

service for

paper currency.

All banknotes graded and encapsulated

by PCGS feature revolutionary

Near-Field Communication (NFC)

Anti-Counterfeiting Technology that

enables collectors and dealers to

instantly verify every holder and

banknote within.

VERIFY YOUR BANKNOTE

WITH THE PCGS CERT

VERIFICATION APP

Merchant Notes from Tuscaloosa, Alabama, in the 1830s:

Benjamin S. Wilson of Conrow, Ramsey & Co.

by Charles Derby

A set of $3 and $5 notes from Tuskaloosa (now

Tuscaloosa), Alabama, from the late 1830s, is known

from unissued cut and uncut sheets, shown in Figures 1

and 2. These notes appear to be generic scrip with many

blank lines to be filled in by the issuer. In addition, a

$10 note, probably from the same series because of

similarities in design and text, is shown in Figure 3, and

though this note is hand signed and dated, it certainly

appears to be falsely issued. However, a legitimately

signed $5 note has been found, shown in Figure 4. The

“attesting” signature on this note is “Benj. S. Wilson”

for the merchant firm “Conrow, Ramsey & Co.” The

town of the branch office that issued this note is

“Tuskaloosa.” The date is difficult to determine, but it

might be a day Jany. 8th 1837 or 1839, but from other

considerations described later, is more likely to be

1839. It is a demand note with the surcharge of “Real

Estate Pledged and Individual Property Liable” though

that pledge carried very little significance at the time.

Who printed these Tuskaloosa notes?

The printer of these Tuskaloosa merchant notes

was almost certainly Draper, Toppan, Longacre &

Company, of Philadelphia and New York [1]. This firm

printed notes for the Mississippi and Alabama Railroad

Company and the Real Estate Banking Company of

Hinds County of Mississippi (Fig. 5), with many

features identical to the Tuskaloosa notes, including the

cotton plant vignette at the left, the goddess vignette at

the center, and the number “5”. Draper, Toppan,

Longacre & Co. formed in 1837 from members of two

firms: Draper, Underwood, Bald, Spencer & Hufty, and

Charles Toppan & Co. In 1840, the firm changed to

Draper, Toppan & Co. Thus, Draper, Toppan, Longacre

& Co. existed only between 1837 and 1840 [1], so the

Tuskaloosa note must have been printed then. The

apparent signed date of 1839 is reasonable.

Who issued these Tuskaloosa notes?

This signing issuer, “Benj. S. Wilson,” is Benjamin

Smith Wilson, of the firm “Conrow, Ramsey & Co.”

Who were these individuals? Benjamin Smith Wilson

was born on May 30, 1808, in Burlington New Jersey.

[2] His parents, Walter Wilson and Amy Shourds

Wilson, were both from Burlington and grew up there

in the Quaker community, in which they also raised

Benjamin and his three older siblings, Anne, Mary, and

James Reed. Amy's parents were Daniel Shourds and

Figure 1. $3 and $5 cut and unissued merchant notes from Tuskaloosa, Alabama

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

94

Christian Belangee Shourds, who were wealthy enough

to own considerable property including a mill in

Tuckerton. Benjamin lived in Burlington until 1825,

when he moved to Philadelphia to join his older brother

James who had moved there the year before, joining the

Quaker community in Philadelphia. [2] The exact

timing and circumstances of his move to Tuscaloosa are

not clear, but he followed in the footsteps of Charles M.

Conrow, who had

moved there by

1830. [3] The

Wilson and Conrow

families were

friends from the

Quaker community

in Burlington, [3] as

were some of the

other business

associates that they

had in Tuscaloosa

and Mobile,

including Guilford

Reed Wilson. [4]

In Tuscaloosa,

Charles became

business partner to

Alexander

McCown, whose

parents had moved

there from

Tennessee and became an established and influential

family. [4] Charles married Alexander’s sister,

Elizabeth, in August 1830. Charles and Alexander

formed a company, McCown & Conrow, which was in

the mercantile business (Fig 6), and from there, the

business expanded.

Benjamin Wilson came to Alabama first in

Mobile, where he worked in the hotel business, and

then by 1835 to Tuscaloosa. [6] An early business

venture of his in 1835

was as proprietor of new

hotel, the Montgomery

Hall, in Montgomery,

Alabama (Figure 7), for

which he solicited

Tuscaloosans to stay

there through

advertisements in the

Tuscaloosan newspaper,

the Flag of the Union. In

fact, this advertisement

extols his business

experience and in the

process explains his

business activities in

Mobile before coming

to Tuscaloosa: “The

undersigned (Wilson)

having served a regular apprenticeship in some of the

best houses in the United States, and long known as the

Proprietor of like Establishments in Mobile and New

Figure 2. Uncut sheet of four of the $3

and $5 notes from Figure 1.

(Courtesy of John Ferreri)

Figure 3. $10 note, likely from the same series as the $3 and $5

notes, but falsely signed and issued. (Courtesy Bill Gunther.

Figure 4. Top: Signed and issued $5 note shown in Figures 1 and

2. (Courtesy of Bill Gunther.

Bottom left: Signature of Benj. S. Wilson.

Bottom right: Signature of Conrow, Ramsey & Co.

Figure 5. Notes printed by Draper, Toppan, Longacre & Co. for the

Mississippi and Alabama Railroad Company, and the Real Estate

Banking Company of Hinds County of Mississippi.

Figure 6. Three advertisements

for the business of McCown &

Conrow. [5]

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

95

Orleans, he is

determined to

consider no

sacrifice, until

he renders the

Montgomery

Hall what has

been so long

needed in this

section of

country – a

genteel and comfortable HOTEL.” After describing the

luxurious offerings at the hotel, he ends with a curious

addendum: “Many slanderous and unfounded reports

having been put in circulation by individuals of

opposite interests – with an evident intention to injure

and prejudice the public mind against the House and

Proprietor – I would respectfully request travelers and

passers-by to give a single call and judge for

themselves. BENJAMIN WILSON.” [6] Besides this

business, Wilson also began buying land in the

Tuscaloosa area at this time. [8]

Wilson quickly became integrated into the

McCown-Conrow family and business in Tuscaloosa.

He married Jane McCown, sister of Alexander

McCown and Elizabeth McCown Conrow, in July

1835. In 1836, Alexander McCown and Charles

Conrow formally dissolved their McCown & Conrow

co-partnership and reformed as a general commission

business (Figure 8). The new arrangement included

Benjamin Wilson and Guilford R. Wilson (Figure 9)

with three branch offices: Alexander McCown & Co. at

Mobile, Charles M. Conrow & Co. at Tuscaloosa, and

Guilford R. Wilson & Co. at New York.

The company prospered and grew, and in

September 1838, and the four partners of the existing

business brought in eight new partners and reformed

and renamed the three branches. As stated in the articles

of co-partnership from September 1838, “Alexander

McCown, Charles M. Conrow, Benjamin S. Wilson,

Guilford R. Wilson, Abel H. White, Robert Oliver,

Chapman A. Hester, Baker Hobson, Pheraudius P.

Brown, Daniel P. Ware, Ambrose K. Ramsey, John

McCain and Benjamin Wilson did agree among

themselves to form a co-partnership for the purpose of

buying and selling all kinds of merchandise, wares and

real estate under the following names: Conrow,

Ramsey & Co. in the city of Tuskaloosa, McCown,

Hobson, Williams & Co. of Mobile, and Hester, Wilson,

White & Co. of New York.” [10] Thus, in 1838,

Conrow, Ramsey & Co.

was formed as the

Tuscaloosa branch of this

business, and Benjamin

Smith Wilson was part of

it. This fact helps to place

the date of the Tuscaloosan

merchant notes to no

earlier than 1838. It also

might explain the

connection with the printer,

Draper, from Philly and

New York – Guildford R.

Wilson and the others in

the New York office might

have helped with these

printing arrangements.

On a personal note, his

marriage to Jane McCown caused

him to be formally disowned by his

Quaker community in

Pennsylvania, as recounted in a

series of letters and documents in

the Quaker records from 1835 and

1836. The statement of removal and

disownment determined that

“Benjamin S. Wilson, who some

time ago removed to reside at

Mobile in the State of Alabama, has

since his residence there

accomplished his Marriage,

contrary to the order of our

Discipline with a person of another religious

profession, and without the consent of his parents. He

has been written to thereafter but as he does not appear

qualified to condemn his separation to the satisfaction

of this meeting we testify that we no longer consider him

a member of the Religious Society of Friends. It is

nevertheless our desire he may become duly sensible of

the nature of his deviation and qualified to be rightly

restored.” [2] He never did return to the Quakers! But

he prospered financially, and in 1837 he bought a new

house in Northport, near Tuscaloosa (Figure 10).

The “Ramsey” in “Conrow, Ramsey & Co.” was

Ambrose Knox Ramsey. He was born in 1795 and

married Nancy Yancey (of Yanceyville, North

Carolina) in 1817. [12–14] In North Carolina, Ambrose

was a wealthy farmer and mill owner, and member of

the state legislature. He moved to Tuscaloosa and

Marengo County in Alabama in 1831, as a pioneer

Figure 7. Montgomery Hall. [7]

Figure 8. Announcement of

business reorganization of

McCown & Conrow to include

Benjamin Wilson. [9]

Figure 9. Guilford

Reed Wilson, born

in Burlington, NJ,

was a relative,

business partner

and namesake of

son of Benjamin

Wilson.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

96

farmer. He established major plantations, at one time

owning 1,200 acres of land. His business venture with

McCown and associates in 1838 expanded his interests

to buying and selling merchandise and wares, but still,

his cotton plantations were his major source of income.

He was president of the Narkeeta, Gainesville, and

Tuscaloosa Rail Road (also called the Mississippi,

Gainesville and Tuscaloosa Railroad), a 22-mile line

that connected to the Mobile & Ohio Railroad in

Mississippi and that had a station named after him. He

moved to Sumter County, Alabama, in 1848. He

weathered the financial storms, and by 1860, owned

$32,000 in real estate and $830,000 in personal estate.

Ramsey died in Meridian, Mississippi, in 1885.

The businesses of Wilson, McCown, Conway,

Ramsey, and associates expanded in

the favorable financial environment

of the mid-1830s. That

environment led to speculative

lending practices in western states

including Alabama, a huge

expansion in cotton production, and

a rapid increase in the market price

of real estate. Then came the Panic

of 1837, a financial crisis that

caused a major recession that

extended into the mid-1840s. This

recession resulting in a severe

shortage of available cash, a crash

in cotton prices, and the collapse of

the real estate bubble. As stated by

Thomas Owen in his History of

Alabama and Dictionary of

Alabama Biography, “The financial panic of 1837,

which convulsed the whole country, was felt with

unusual severity in Alabama. For some years a spirit of

speculation had been growing and spreading,

stimulated by increased bank circulation and unlimited

credit facilities. Extravagant investments in lands and

slaves were made. Property of all kinds reached

fictitious values. When the crash came the banks

suspended specie payments, and all classes of business

stagnated. Thousands of good men were ruined.

Numbers emigrated to the newer States or Territories.”

[15]

So it was with Benjamin Wilson, Charles Conrow,

Alexander McCown, and their families. Newspapers

records from the late 1830s and early 1840s show that

Wilson, Conrow, McCown, and others were financially

stretched and threatened, eventually leading to financial

collapse and closure of their business. Legal action was

taken against them, with lawsuits filed, liens placed,

and public sales of their foreclosed properties. They

filed for bankruptcy (Figure 11). Wilson tried to make

ends meets, by partnering with Tuscaloosan merchant

and businessman Charles Snow (Figure 12). But

Wilson, Conrow, and McCown looked to the next

western frontier – to Texas – for escape from their

Alabama woes and for new opportunities and a better

life. As early as the late 1830s, they began looking to

Texas. In 1839, Alexander McCown and brother James

went to Texas, where they applied for and purchased

land, then returned to Alabama, where they filed for

bankruptcy and prepared to move. In 1841 with their

mother, brothers Sampson and Jerome, the McCowns

moved to Texas, James to Marshall and Alexander to

Figure 10. Benjamin S. Wilson’s house in

Northport/Tuscaloosa, built in 1837 on an eight-acre lot, is

typical of smaller houses in Tuscaloosa during the antebellum

period. The house, now called the Wilson-Clements House, still

stands to the day and since 1975 has been on the Alabama

Register of Historic Places. [11]

Figure 11. By purchasing land and moving

to Texas and by filing for bankruptcy,

Benjamin Wilson, Charles Conrow, and

others avoided some of their legal and

financial responsibilities, as shown by

these two articles from 1841 and 1842 in

The Independent Monitor. [16]

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

97

Montgomery. The Wilsons and Conrows also moved to

Texas around that time, the Wilsons to Huntsville,

Texas, and the Conrows to Montgomery County,

Texas, only 30 miles distant.

Life in Texas

The available records of Benjamin Wilson up until

this point in his life paint the picture of an adventurer

who moved from the Quaker community of the

northeast to the western frontier of Alabama, and then

after having faced economic failure in Alabama, risked

the challenges of a move even further west to the Texas

frontier of the 1840s. Still, we do not have a deeper

impression of the personality of Benjamin Wilson until

we read records from his time in Texas, especially the

published letters by his friend Sam Houston [18] and

articles in the Huntsville, Texas, newspaper at the time.

Benjamin and Jane Wilson arrived in Huntsville,

Walker County, Texas, around 1842, and they quickly

landed on their feet and built an impressive life.

Married since 1835 and childless, Benjamin and Jane

must have found life in Texas fruitful, for they had five

children, all sons, over the next 13 years. They were

named Walter (b. 1843), James Reed (b. 1845), Sam

Houston (b. 1848), Benjamin (b. 1852), and Guilford

Reed (b. 1856), after Benjamin’s relatives and business

partners. Benjamin Wilson returned to his business

roots as a merchant and hotel proprietor. His hotel was

The Eutaw Hotel, established in 1850. Named by

Wilson after the Alabaman city, it was a popular

hostelry and stagecoach stop, consisting of a two-story

frame building, with a large cistern, well, livery stable,

and other associated buildings. The Eutaw Hotel

operated for over 50 years. A historical marker notes

its location today. [17]

Wilson became friends with Sam Houston, the

famous Texan who was the first president of the

Republic of Texas, governor and senator from the state

of Texas, and resident of Huntsville, Texas (Figure 13).

Sam Houston’s letters show that Benjamin and Sam,

and their wives

Jane and

Margaret (Figure

13), had a

complicated

relationship. On

the one hand, the

Wilson’s named

their third son

after Sam in

1848. To this,

Margaret wrote

to her husband,

“Mrs. Wilson’s

boy is a noble looking fellow, & appropriately named I

think, for he is exceeding like you. You must be very

proud of the name.” [18] On the other hand, Wilson the

merchant sold items to Houston, but Sam notes to

Margaret of some distrust of Wilson’s “avarice” in his

business practices. Then there was the Thorne-Gott

affair. The Houston’s took on Virginia Thorne, a

teenage orphan, as their ward. After months of

problems with Virginia Thorne, Margaret beat her with

a cowhide, and Virginia ran off with Thomas Gott,

overseer of the Houston’s Woodland Farm. Gott and

Thorne returned to Huntsville and filed charges of

assault and battery against Margaret. A subsequent

legal hearing led to a recommendation that the case be

considered by the Baptist Church, which fully acquitted

Margaret. The Houston-Wilson controversy started

when the Wilson’s accepted Virginia into their house

after she returned to Huntsville and filed charges. This

caused a strain on the relationship, leading Margaret to

write to Sam that “Mrs. Wilson is a raving maniac. It is

one of the most melancholy cases of insanity that I have

ever heard of.” The Houston’s and Wilson’s seem to

have reconciled, but it was a rocky time. [19]

Two more stories from Huntsville tell of Wilson’s

personality. The first is the time of a fire in the barn

next to Wilson’s Eutaw Hotel. Wilson was said to have

asked the hotel residents to pray for the wind to shift. It

did, and the hotel was saved [18]. The second anecdote

comes from an 1872 newspaper story by a “Special

Traveling Agent.” [20] The agent reported that, “On

arriving at Huntsville I heard all the passengers speak

Figure 12. Benjamin Wilson became the junior partner in a business with Charles Snow in 1841, as

shown by these two articles from in The Independent Monitor. [17]

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

98

of going to Wilson’s Hotel, so I followed the crowd, and

at the station we found a fine omnibus with a spend

team of gray horses waiting to take us to the Eutaw

House, kept by mine host, Colonel, Benjamin S. Wilson,

an old Texan having resided at this place as master of

the surveys for the past thirty years. I found myself no

stranger in the hands of Colonel Wilson, who made me

welcome in the old Texas fashion, and I felt quite at

home, like all cosmopolites ought to feel. I cannot pass

by without some allusion to the Eutaw House, at

Huntsville, which is well kept, quite an improvement on

what I fell in with when wending my way through this

little hamlet three years ago. The Colonel, himself, is

no ordinary individual, and is regarded as one of the

curiosities of the place, and is, in truth, most excellent

good company, entertaining his guests with an

inexhaustible store of genuine wit and good humor.

May he live long to enjoy the profits of his industry,

energy and enterprise.”

Benjamin Wilson did live well past this encounter,

much longer than did his former Tuscaloosan business

partners, Charles Conrow and Alexander McCown,

who died in Texas in the 1840s and 1850s respectively.

While Benjamin Wilson’s death and final resting place

are not clear, he lived in Huntsville with his youngest

son at least until 1880, then 72 years old. [21]

References and Footnotes

[1] American Bank Note Company. https://www.coxrail.com/abnco.asp

[2] U.S. Quaker Meeting Records, 1681-1935. Accessed through ancestry.com

[3] Alexandra Genetti, personal communication

[4] Ancestry.com

[5] Advertisements from 1836 in the Flag of the Union, Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

[6] October 10, 1835, issue of the Flag of the Union, Tuscaloosa, Alabama

[7] From Blue, Matthew Powers. 2010. The Works of Matthew Blue: Montgomery's First Historian. NewSouth Books.

[8] United States Bureau of Land Management. Alabama Pre-1908 Homestead and Cash Entry Patent and Cadastral Survey Plat Index.

General Land Office Automated Records Project, 1996.

[9] September 3, 1836, issue of the Alabama State Intelligencer, Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

[10] Early Deeds of Itawamba County, Mississippi: 1836-1839 Including A Brief History of Early Itawamba County. 2008. The

Itawamba Historical Society.

[11] Brown, Donald and Hannah Brown. 2010. Tuscaloosa: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. Beers & Associates, LLC.

[12] Perrin, William Henry. 1891. Southwest Louisiana and Biographical and Historical.

[13] Berney, Saffold. 1878. Handbook of Alabama: A Complete Index to the State. Mobile Register Print.

[14] Obituary in the New Orleans Christian Advocate, June 24, 1886.

[15] Owen, Thomas McAdory. 1921. History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography. The S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., Chicago.

[16] The Independent Monitor, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Issues of June 3, 1841 (right), and August 17, 1842 (left)

[17] The Independent Monitor, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Issues of May 12, 1841 (left, and August 17, 1842 (right)

[18] www.waymarking.com/waymarks/ WMY0ER_The_Eutaw_House_Huntsville_TX

[19] The Personal Correspondence of Sam Houston: 1852-1863. University of North Texas Press, 1996.

[20] The Galveston Daily News, Galveston, Texas. Issue from April 26, 1872.

[21] U.S. Census, 1880, Huntsville, Texas.

Acknowledgments: I am most appreciative to Alexandra Genetti for sharing her fantastic research on Charles Conrow and family, which has

been a tremendous help in writing this article. John Ferreri, Bill Gunther, and Hugh Shull have kindly shared their notes and encouraged this

study.

Figure 13. Sam and Margaret Houston,

friends of Benjamin and Jane Wilson in

Huntsville, Texas.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

99

Legal Tender

Series of 1928

Non-Star Serial Number Ranges

Purpose and Overview

The objective of this article is to provide a big picture overview of the Series of 1928 $2 notes to

illustrate how the various varieties that make up the series fit together. Sufficient information will be

provided to allow you to determine at least to the year when your Series of 1928 legal tender notes were

delivered to the Treasury from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. The serial number ranges for the

varieties are updated by new finds that have been reported to me or that I have observed.

Most currency collectors collect $2 bills because they are America’s orphan denomination. Use of

$2s never caught on with the public so there aren’t even slots for them in cash registers. When they leave a

bank, they tend to come right back. Consequently, they don’t circulate in the traditional sense of the word.

They simply constitute an exotic breed that are treated as curiosities by most people. That is their appeal.

The $2 Series of 1928 legal tender notes with their large red seals constitute the most varied of the

small size $2 types. The series sports seven Treasury signature combinations as well as a number of face

and back varieties.

Knowing when those in your possession were printed may add to their appeal. All of these notes

are over 50 years old so they are older than most of you.

Early cataloguers Leon Goodman, John Schwartz and especially Chuck O’Donnell solicited reports

of serial numbers for the various varieties in order to develop bracketing serial number ranges for their

usage. For a time, collectors avidly participated and successive catalogs reflected refinements to those

ranges. Unfortunately, this activity has waned considerably in the past few decades. It is long overdue to

assemble the known updates so a new cut at the job can be presented here. Sooner or later, you will find

notes among your holdings that fall outside the known ranges. You can broker that information through me

for these popular $2s and we’ll publish updates.

Production by Year

Table 1 allows you to determine the year when a given 1928 $2 was delivered from the Bureau of

Engraving and Printing to the U. S. Treasurer for issue to the public. In fact, for the years 1929 through

1948 the cut can be made to within 6 months because end of fiscal year serials for those years also are

The Paper

Column

Peter Huntoon

Figure 1. Series of 1928C mule with the highest reported serial number for this scarce variety.

Macro face plate B179, micro back plate 291. Heritage Auction archives photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * March/April 2023 * Whole Number 344

100

available. Yearly production is graphically illustrated on Figure 2.

Signatures Changes

Table 2 lists the Treasury signature combinations that occur on the notes along with the periods

during which the printing plates bearing those signatures were on the presses. Supplemental details

pertaining to the plates appears in Table 4 at the end of this article.

An important finding revealed on Table 2 is that usage of plates with obsolete Treasury signatures

generally overlapped production from plates with current signatures during a transition period of variable

length. This occurred because the signatures were on the intaglio face plates rather than being overprinted

and it was the policy of the Treasury to have the BEP use still serviceable plates until they wore out.

Other Design Changes

Four changes were made to the intaglio plates other than the Treasury signatures during the life of

the Series of 1928 $2s. These included: (1) an increased vertical separation between the subjects on the

plates, (2) revised legal tender clause on the face plates accompanied by addition of engraved filigree inside

the borders and raised placement of the right plate letter and number, (3) increased size of the plate numbers

on both the back and face plates, and (4) decreased width of the face plates.

Table 1. Yearly serial numbers for deliveries of $2 Series of 1928

legal tender notes from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to the

Treasury Department.

First Note Last Note Number Cumulative Ending

Delivered Delivered Printed Number Serial Number

Year in Year in Year in Year Printed on June 30

1929 A00000001A A37548000A 37,548,000 37,548,000 A18000000A

1930 A37548001A A58860000A 21,312,000 58,860,000 A53196000A