Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

Series 1929 $100 NBNs Rarity--Lee Lofthus

$20 Series 1880 LT Serial Number Color Change--Peter Huntoon

Civil War Stamp Money--Steve Feller

Glass-Borah Amendment--Peter Huntoon

Gardiner H. Wright & Co.--Terry Bryan

The Promise of a Florida Soldier--Charles Derby

1940 Emergency Issue of Deventer, The Netherlands--Roeland Krul

UNESCO World Heritage Sites-Algeria--Roland Rollins

The Mystery of the Missing Statue--Tony CHibbaro

Wobus Postal Note--Bob Laub

official journal of

The Society of Paper Money Collectors

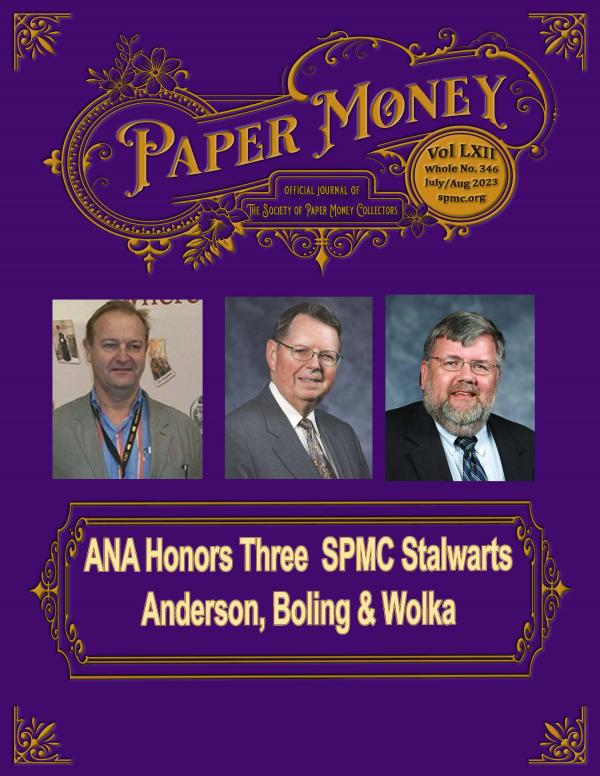

ANA Honors Three SPMC Stalwarts

Anderson, Boling & Wolka

America’s Oldest and Most Accomplished Rare Coin Auctioneer

1550 Scenic Ave., Suite 150, Costa Mesa, CA 92626 • 949.253.0916

470 Park Ave., New York, NY 10022 • 212.582.2580 • NYC@stacksbowers.com

84 State St. (at 22 Merchants Row), Boston, MA 02109 • 617.843.8343 • Boston@StacksBowers.com

1735 Market St. (18th & JFK Blvd.), Philadelphia, PA 19103 • 267.609.1804 • Philly@StacksBowers.com

Info@StacksBowers.com • StacksBowers.com

California • New York • Boston • Philadelphia • New Hampshire • Oklahoma • Virginia

Hong Kong • Paris • Vancouver

SBG PM Aug2023 HLs 230601

LEGENDARY COLLECTIONS | LEGENDARY RESULTS | A LEGENDARY AUCTION FIRM

Featured Highlights from the

STACK’S BOWERS GALLERIES

August 2023 Global Showcase U.S. Currency Auction

Auction: August 14-19, 2023 • Costa Mesa, CA

Expo Lot Viewing: August 6-11, 2023 • Pittsburgh, PA

Contact Us for More Information Today!

West Coast: 800.458.4646 • East Coast: 800.566.2580 • Info@StacksBowers.com

Fr. 197a. 1863 $20 Interest Bearing Note.

PMG Very Fine 20.

Fr. 2123-G. 1988 $50 Federal Reserve Note. Chicago.

PCGS Currency Very Fine 30.

From the Issie Chaimovitch Collection of Radars.

Fr. 37. 1917 $1 Legal Tender Note.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 66 EPQ.

From the Wisconsin Collection.

Fr. 2173-B. 1990 $100 Federal Reserve Note.

New York. PMG Choice About Uncirculated 58 EPQ.

From the Issie Chaimovitch Collection of Radars.

Fr. 280m. 1899 $5 Silver Certificate Mule Note.

PMG Choice Uncirculated 64.

From the Wisconsin Collection.

Fr. 1600. 1928 $1 Silver Certificate.

PCGS Currency 64 PPQ.

From the Issie Chaimovitch Collection of Radars.

Fr. 2175-A. 1996 $100 Federal Reserve Note. Boston.

PMG Choice Uncirculated 63 EPQ.

Binary-Radar-Rotator S/N.

From the Wisconsin Collection.

MD-44. Maryland. January 1, 1767. $1.

PCGS Banknote Gem New 65 PPQ.

From the Mid-Continent Collection.

SC-153. South Carolina. February 8, 1779. $40.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

From the Mid-Continent Collection.

Fr. 1152. San Francisco, California. $20 1870.

The First National Gold Bank. Charter #1741.

PMG Very Fine 25.

CC-59. Continental Currency.

February 26, 1777. $6.

PMG Superb Gem Uncirculated 67 EPQ.

From the Mid-Continent Collection.

Fr. 2221-G. 1934 $5000 Federal Reserve Note.

Chicago. PMG Choice Uncirculated 64 EPQ.

253 Series 1929 $100 NBNs Rarity--Lee Lofthus

266 $20 Series 1880 LT Serial Number Color Change--Peter Huntoon

269 Civil War Stamp Money--Steve Feller

276 Glass-Borah Amendment--Peter Huntoon

282 Gardiner H. Wright & Co.--Terry Bryan

284 The Promise of a Florida Soldier--Charles Derby

288 1940 Emergency Issue of Deventer, The Netherlands--Roeland Krul

292 UNESCO World Heritage Sites-Algeria--Roland Rollins

294 The Mystery of the Missing Statue--Tony CHibbaro

286 Wobus Postal Note--Bob Laub

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

247

274 Central National Bank of Frederick, MD--J. Fred Maples

Columns

Advertisers

SPMC Hall of Fame

The SPMC Hall of Fame recognizes and honors those individuals who

have made a lasting contribution to the society over the span of many years.

Charles Affleck

Walter Allan

Doug Ball

Hank Bieciuk

Joseph Boling

F.C.C. Boyd

Michael Crabb

Forrest Daniel

Martin Delger

William Donlon

Roger Durand

C. John Ferreri

Milt Friedberg

Robert Friedberg

Len Glazer

Nathan Gold

Nathan Goldstein

James Haxby

John Herzog

Gene Hessler

John Hickman

William Higgins

Ruth Hill

Peter Huntoon

Glenn Jackson

Don Kelly

Lyn Knight

Chet Krause

Allen Mincho

Clifford Mishler

Barbara Mueller

Judith Murphy

Dean Oakes

Chuck O’Donnell

Roy Pennell

Albert Pick

Fred Reed

Matt Rothert

John Rowe III

Herb & Martha

Schingoethe

Hugh Shull

Glenn Smedley

Raphael Thian

Daniel Valentine

Louis Van Belkum

George Wait

D.C. Wismer

From Your President

Editor Sez

New Members

Uncoupled

Chump Change

Obsolete Corner

Quartermaster

Cherry Picker Corner

249

250

251

298

304

305

308

311

Robert Vandevender

Benny Bolin

Frank Clark

Joe Boling & Fred Schwan

Loren Gatch

Robert Gill

Michael McNeil

Robert Calderman

Stacks Bowers Galleries IFC

Pierre Fricke 247

Greysheet 275

Tom Denly 281

Higgins Museum 283

Fred Bart 289

PCGS-C 290

MPC Book 291

DBR Currency 293

Benny Bolin 295

Bob Laub 297

Lyn Knight 310

FCCB 313

ANA 314

PCDA 315

Heritage Auctions OBC

Fred Schwan

Neil Shafer

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

248

Officers & Appointees

ELECTED OFFICERS

PRESIDENT Robert Vandevender II

rvpaperman@aol.com

VICE-PRES/SEC'Y Robert Calderman

gacoins@earthlink.net

TREASURER Robert Moon

robertmoon@aol.com

BOARD OF GOVERNORS

APPOINTEES

PUBLISHER-EDITOR

Benny Bolin smcbb@sbcglobal.net

ADVERTISING MANAGER

Wendell Wolka purduenut@aol.com

Megan Reginnitter mreginnitter@iowafirm.com

LIBRARIAN

Jeff Brueggema

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

Frank Clark frank_clark@yahoo.com

IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT

Shawn Hewitt

WISMER BOOk PROJECT COORDINATOR

Pierre Fricke

From Your President

Robert Vandevender IIFrom Your President

Shawn Hewitt

Paper Money * July/August 2020

6

jeff@actioncurrency.com

LEGAL COUNSEL

n

Mark Anderson mbamba @aol.com

Robert Calderman gacoins@earthlink.com

Matt Drais stockpicker12@aol.com

Mark Drengson markd@step1software.com

Jerry Fochtman jerry@fochtman.us

Pierre Fricke pierrefricke@buyvintagemoney.com

Loren Gatch lgatch@uco.edu

William Litt billlitt@aol.com

J. Fred Maple s maplesf@comcast.net

Cody Regenitter cody.reginnitter@gmail.com

Andy Timmerman andrew.timmerman@aol.com

Wendell Wolka purduenut@aol.com

Greetings. During our June Executive Board meeting, we held an election

for the four officers of our organization. I would like to thank the Board of

Governors for selecting me as your President for my second and final 2-year

term. Our Vice President and Secretary Robert Calderman along with our

Treasurer Robert Moon will also continue serving in those positions for the

next two years.

For a time, it appeared we were going to have a contested election for our

Board of Governors. During this election, we were planning to have voting

via electronic means as the primary method while continuing to have the

ability to distribute paper ballots to those individuals who requested one. As

some of you may know, after many years of serving on our Board, both Mark

Anderson and J. Fred Maples decided not to run for reelection but to

continue to support the organization as regular members. This decision by

them freed up two additional spots on our board eliminating the need for a

contested election this year. I am happy to welcome two new members to

our Board of Governors, Derek Higgins, and Raiden Honaker. You can read

more about them in this issue.

Although not needed for this election, it made sense to continue with a

revision of our bylaws to accommodate the new electronic voting process

potentially needed in the future. The new updated bylaws were ratified by

our Executive Board on June 12th and are available at our website for review.

During the third week of June, after my submittal deadline for this article, we

are planning to staff an SPMC table at the Long Beach Expo. If this show

turns out to be like the previous ones, we should see a significant amount of

traffic with many people stopping by our table to either say hello or to

inquire about our organization. I will be walking the floor for a day at the

upcoming Summer FUN show in Orlando, but the SPMC will not have a

table. In August, we will be heading to Pittsburgh and helping to staff the

SPMC table at the ANA World Fair of Money. I look forward to seeing some

of you there.

Looking forward, one of the things our Society needs to consider is

succession planning for key positions. If you think you are qualified and

interested in potentially becoming our Secretary or Treasurer at some time in

the future, please contact one of our board members. I am sure our highly

efficient Treasurer, Bob Moon, and Secretary, Robert Calderman, would be

happy to work with an understudy!

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

249

Terms and Conditions

The Society of Paper Money Collectors (SPMC) P.O. Box 7055,

Gainesville, GA 30504, publishes PAPER MONEY (USPS 00‐

3162) every other month beginning in January. Periodical

postage is paid at Hanover, PA. Postmaster send address

changes to Secretary Robert Calderman, Box 7055, Gainesville,

GA 30504. ©Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc. 2020. All

rights reserved. Reproduction of any article in whole or part

without written approval is prohibited. Individual copies of this

issue of PAPER MONEY are available from the secretary for $8

postpaid. Send changes of address, inquiries concerning non ‐

delivery and requests for additional copies of this issue to

the secretary.

MANUSCRIPTS

Manuscripts not under consideration elsewhere and

publications for review should be sent to the editor. Accepted

manuscripts will be published as soon as possible, however

publication in a specific issue cannot be guaranteed. Opinions

expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect those of the

SPMC. Manuscripts should be submitted in WORD format via

email (smcbb@sbcglobal.net) or by sending memory stick/disk

to the editor. Scans should be grayscale or color JPEGs at

300 dpi. Color illustrations may be changed to grayscale at the

discretion of the editor. Do not send items of value.

Manuscripts are submitted with copyright release of the author

to the editor for duplication and printing as needed.

ADVERTISING

All advertising on space available basis. Copy/correspondence

should be sent to editor.

All advertising is pay in advance. Ads are on a “good faith”

basis. Terms are “Until Forbid.”

Ads are Run of Press (ROP) unless accepted on a premium

contract basis. Limited premium space/rates available.

To keep rates to a minimum, all advertising must be prepaid

according to the schedule below. In exceptional cases where

special artwork or additional production is required, the

advertiser will be notified and billed accordingly. Rates are

not commissionable; proofs are not supplied. SPMC does not

endorse any company, dealer, or auction house. Advertising

Deadline: Subject to space availability, copy must be received

by the editor no later than the first day of the month

preceding the cover date of the issue (i.e. Feb. 1 for the

March/April issue). Camera‐ready art or electronic ads in pdf

format are required.

ADVERTISING RATES

Editor Sez

Benny Bolin

Required file submission format is composite PDF v1.3

(Acrobat 4.0 compatible). If possible, submitted files should

conform to ISO 15930‐1: 2001 PDF/X‐1a file format standard.

Non‐ standard, application, or native file formats are not

acceptable. Page size: must conform to specified publication

trim size. Page bleed: must extend minimum 1/8” beyond

trim for page head, foot, and front. Safety margin: type and

other non‐bleed content must clear trim by minimum 1/2”.

Advertising c o p y shall be restricted to paper currency, allied

numismatic material, publications, and related accessories.

The SPMC does not guarantee advertisements, but accepts

copy in good faith, reserving the right to reject objectionable

or inappropriate material or edit copy. The SPMC

assumes no financial responsibility for typographical

errors in ads but agrees to reprint that portion of an ad in

which a typographical error occurs. Benny

Space

Full color covers

1 Time

$1500

3 Times

$2600

6 Times

$4900

B&W covers 500 1400 2500

Full page color 500 1500 3000

Full page B&W 360 1000 1800

Half‐page B&W 180 500 900

Quarter‐page B&W 90 250 450

Eighth‐page B&W 45 125 225

Summer is here and it came with a vengence. Record setting and

dangerous heat and the humidity made it feel about 10 degrees hotter

than it really is. Here is Texas, we have one word for that

phenomenon--SUMMER! All kidding aside, stay safe out there and

limit your outdoor activities and DRINK LOTS OF WATER--H2O,

Agua, Wasser, Acqua, Aqua!

The front cover of this issue is dedicated to three truly great men

in SPMC circles and paper collecting in general--Mark Anderson,

Joe Boling & Wendell Wolka. The ANA awarded Mark with a

Medal of Merit and Wendell the 2023 Lifetime Achievement Award.

I have been fortunate enough to know and work with both for many

years, on the board, as an officer and friend. My fondest memories of

the two are having Mark drive me and my family around NYC--he

can put NYC taxi drivers to shame and of Wendell as emcee of our

annual Tom Bain breakfast Raffle! Both have a wit that is sharp,

unparalelled knowledge and humor that is infectious. You can never

be in a bad mood when they are around. Mark is on the board of the

Higgins Museum and has received an ANA President's award.

Wendell has received the Glenn Smedly award from the ANA and is

a prolific writer, researcher and a workhorse for the SPMC. Both are

multiple award winners from the SPMC. Both have received the

Nathan Gold Award (our highest award), an Education, Research

and Outreach award, and multiple Presidents awards. In addition,

Mark received the Best-in Show exhibit award for his exhibit on

Swedish Plate Money and Wendell the Founders award, a Forrest

Daniel award and a Wismer award both for literary excellence and

was named a Numismatic Ambassador award in 1985.

I have worked with Joe for all my years as editor. He has been a

great teacher and author. He has co-authored Paper Money's

Uncoupled column for many years with his buddy, Fred Schwan. Joe

has also received the Best in Show exhibit award from the SPMC, a

Forrest Daniel literary award and was inducted into the SPMC Hall

of Fame in 2017. He also has won an ANA medal of Merit, the

Glenn Smedley award, The Farran Zerbe Memorial award, an

Exemplary Service and President's award.

The SPMC and the hobby in general say collectively

CONGRATULATIONS & THANK YOU to these three men!

My apologies for not stating that Howard Cohen was FCCB

member number 37. I apologize for this oversight.

I made a plea for short to semi-short articles (1-4 pages) in

the last issue. You responded well. I am asking this time for

4-8 page articles. Write about anything paper related and see

your name as a by-line.

Have a happy and safe summer and I hope to see you all

some day at a show although I dont generally get to many.

250

The Society of Paper Money

Collectors was organized in 1961 and

incorporated in 1964 as a non-profit

organization under the laws of the

District of Columbia. It is

affiliated with the ANA. The

Annual Meeting of the SPMC is

held in June at the International

Paper Money Show. Information

about the SPMC, including the

by-laws and activities can be

found at our website--

www.spmc.org. The SPMC does

not does not endorse any dealer,

company or auction house.

MEMBERSHIP—REGULAR and

LIFE. Applicants must be at least 18

years of age and of good moral

character. Members of the ANA or

other recognized numismatic

societies are eligible for membership.

Other applicants should be sponsored

by an SPMC member or provide

suitable references.

MEMBERSHIP—JUNIOR.

Applicants for Junior membership

must be from 12 to 17 years of age

and of good moral character. A parent

or guardian must sign their

application. Junior membership

numbers will be preceded by the letter

“j” which will be removed upon

notification to the secretary that the

member has reached 18 years of age.

Junior members are not eligible to

hold office or vote.

DUES—Annual dues are $39. Dues

for members in Canada and Mexico

are $45. Dues for members in all

other countries are $60. Life

membership—payable in installments

within one year is $800 for U.S.; $900

for Canada and Mexico and $1000

for all other countries. The Society

no longer issues annual membership

cards but paid up members may

request one from the membership

director with an SASE.

Memberships for all members who

joined the Society prior to January

2010 are on a calendar year basis

with renewals due each December.

Memberships for those who joined

since January 2010 are on an annual

basis beginning and ending the

month joined. All renewals are due

before the expiration date, which can

be found on the label of Paper

Money. Renewals may be done via

the Society website www.spmc.org

or by check/money order sent to the

secretary.

WELCOME TO OUR

NEW MEMBERS!

BY FRANK CLARK

SPMC MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

NEW MEMBERS 05/05/2023 NEW MEMBERS 06/05/2023

15572 Don Smith, Don Kelly

15573 Brian Bazarnicki, Greensheet

15574 Mark Agisotelis, Currency

Face Book Group

15575 Melissa Lumaye, Website

15576 Robert Dreaper, Website

15577 Logan Track, Rbt Calderman

15578 Walt Sanjuan, Gary Dobbins

15579 Jossie Hernandez, Website

15580 June Latorre, Website

15581 Benjamin Doss, Website

15582 Cary Belger,

15583 Carlos Fuster,

15584 Bill Fannon, Website

15585 Scott Garfinkel, Website

REINSTATEMENTS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

LM465 Mike W. Thompson, Website

Dues Remittal Process

Send dues directly to

Robert Moon

SPMC Treasurer

104 Chipping Ct

Greenwood, SC 29649

Refer to your mailing label for when

your dues are due.

You may also pay your dues online at

www.spmc.org.

15556 Joseph Ford, Website

15557 Rich Voninski, Website

15558 Jeffrey Harmon, Website

15559 Daniel Fellows, Website

15560 Mohammed Khashabi, Website

15561 Aaron T. Allan

15562 George Cuhaj, Website

15563 Jim Wendoll, Michael McNeil

15564 Richard Stachurski, Website

15565 Stephen Fitzmartin, Website

15566 Karl Howard, Raiden Honaker

15567 Louis Padgug, Website

15568 Will Harvey, Website

15569 Angel Navarro Zayas, Website

15570 Troy Snelling, Frank Clark

15571 Steven Arck, Jeff Brueggeman

Reinstatements

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

Correction - LM465 Liran Max Renert,

Correction - LM466 Mike W. Thompson,

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

251

Governor Elections

Due to current sitting governors Mark Anderson and Fred Maples deciding not to run for re-election, the following

two governors who had submitted all required documents for positions and the two current governors who were

standing for re-election are hereby elected by the board of governors by vote per our bylaws.

Returning Governors

Loren Gatch

Loren was first elected to the

board of governors in 2015. He

has taught political science at the

University of Central Oklahoma

since 1998. With collecting

interests in scrip, emergency

monies, and different types of

fiscal paper, Gatch has published

on these topics in Paper Money since the mid-2000s.

For the last eight years he has produced the weekly

“News & Notes” blog that is received by SPMC

members as an email and which appears on the SPMC

website. He also publishes occasional pieces about

fiscal paper on a separate blog on the website.

William Litt

William Litt has been an SPMC

governor since 2020. He started

collecting U.S. paper money in

1980, at the age of thirteen, after

having collected coins for several

years. Since the early 1980s, Bill

has been an active collector of, and

part-time dealer in, U.S. currency, with a particular

love of National Bank Notes and National Bank

memorabilia. He collects Nationals from seven

counties in Northern and Central California. Bill

graduated from Cornell University and the UCLA

School of Law, and has practiced law since 1993.

New Governors

Derek Higgins

Derek was born and raised in

Lincoln, Nebraska, and started

his collecting journey as a child

with stamps, National

Geographic Magazines, and

coins/paper money. His interest

really took off when his

grandmother gave him an old Army sock full of coins

and tokens collected during his grandfather’s WWII

service in Europe. Regular visits to The Coinery in

Lincoln were the gateway to diving deeper into the

hobby, learning about coins and paper money both

world and domestic. A devastating house fire in 2011

decimated his coin collection, but by some divine

miracle his paper money collection survived because

he had it with him in his college dorm the day of the

fire. From then on paper money, specifically United

States small size varieties and regular issues, North

Idaho Nationals, and Lancaster County Nebraska

Nationals have become his collecting focus. Now

living in Aurora, Colorado, he and his wife have a

budding online dealer business and work diligently to

advance the profile of the hobby through social media

and their presence at local shows.

Raiden Honaker

Raiden was born and raised in the

small town of Vidalia, Georgia,

and found his passion in

numismatics at the young age of 8.

Ever since, he has been actively

collecting, expanding his

knowledge, and has maintained his

passion for nearly two decades. His love and specialty

for paper money began when he first learned of

National Bank Notes in his early teens. Raiden became

a part-time dealer of coins and paper currency in his

late teens after moving to Carrollton, Ga to attend the

University of West Georgia. There, he graduated with

a BBA in Management and Marketing in 2019, and a

Master of Business Administration in 2020. In January

2021, he joined Heritage Auctions as a US Paper

Currency Consignment Director and Specialist. He is

a member of the SPMC, IBNS, ANA, Texas

Numismatic Association (TNA), Georgia Numismatic

Association (GNA), Paper Money Collectors of

Michigan (PMCM), and the CSA Trainmen. An

exceptionally avid collector of Georgia National Bank

Notes, he is currently working on a publication on the

history and background of his home state’s National

Banks during the issuing period.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

252

Series of 1929 $100 Type 2 Nationals

Rarity viewed through the

Hickman & Oakes Auction Sales

Lee Lofthus

Introduction

he 1929 $100 Type 2 national bank notes are the rarest denomination and type of

the small size nationals. Excepting the $500 and $1,000 large size nationals, they

are the scarcest of any national bank note type and denomination. Only 403 $100

Type 2 notes are recorded in the National Bank Note Census. Very few appear on the market each

year, and their scarcity has served to keep them largely out of the current numismatic spotlight.

This article provides a brief background on the conditions that spawned the $100 Type 2 notes,

and looks back to the heyday of early national bank note auctions in the 1970’s and 1980’s to see

the prevalence of these notes in the marketplace when national bank note collecting first caught

fire.

T

Figure 1. Rare Hawaii $100 Type 2. While $100 Type 1 notes from the bank are

common, Type 2 notes are a different matter, with only 3 reported. The finest

recorded is shown above. All the $100 Type 2 notes carry the bank’s third title.

Image courtesy James Simek.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

253

Type 2 National Bank Notes

Type 2 nationals are distinguished by two features: sequential serial numbers for each note

(versus the sheet numbers found on Type 1 notes) and the addition of a second set of charter

numbers printed in brown ink on the face of the notes adjacent to the serial numbers. These

improvements came as multiple offices in the Treasury Department sought to address ongoing

complaints with the Type 1 nationals. A full discussion of the problems and Treasury Department

deliberations that led to the Type 2 designs is in the Huntoon-Shiva Encyclopedia (2022) and

Huntoon/Lofthus/Simek (2011).

Arrival in the Great Depression’s Shadow

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) began the delivery of Type 2 national bank

notes on May 27, 1933. The first $100 Type 2 notes were sent to the Comptroller of the Currency

on June 24, 1933. The nation was deep into the Great Depression and the banks were in crisis.

There were 7,536 national banks operating as of June 30, 1929. In October of 1929 the

stock market crashed. By early March 1933, just 5,916 national banks were operating. By June 30,

1934, 5,422 were in operation but only 4,600 were issuing national bank notes. It was an

inauspicious time for the Type 2 notes to come on the scene.

On March 6, 1933, newly inaugurated president Franklin Roosevelt declared a bank

holiday in an effort to restore confidence in banks and stop runs by frightened depositors. The

holiday closed the nation’s banks until they could be examined by federally-appointed bank

examiners for soundness before reopening. Only 4,510 were licensed to open without restriction

on March 13-15, although others were able to exit receivership in the months ahead.

Just as the Type 2 notes arrived, overall circulation of national bank notes began declining.

There had been a temporary surge in circulation in 1932 and early 1933 due to an extraneous

proviso added onto the Federal Home Loan Bank Act legislation that extended the circulation

privilege to a broader array of government bonds for a period of three years. The additional bonds

temporarily pumped more national bank notes into circulation to help ease the money shortages.

Circulation of nationals peaked in May 1933, but declined thereafter.

Figure 2. The only $100 Type 2 issue from Rhode Island, and the only national

bank to use “hospital” in its title. The Rhode Island Hospital Trust Company

opened in 1867, founded by the nearby hospital’s trustees. In December 1933, the

trust operations and banking operations were separated, and the bank operation

took national charter 13901. Author image.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

254

In the 1933 Depression days of “brother, can you spare a dime?” a $100 bill was a

significant amount of purchasing power, so the demand for $100 bills was limited. It is no wonder

the $100 Type 2 notes are so scarce.

Figure 4. Texas had the most

banks that issued $100 Type

2 notes. Dallas had two of

eight issuing banks. Even the

two big city Dallas banks

combined issued only 3,229

$100 Type 2 notes. The

smallest Texas issuer was the

Central National Bank of

McKinney with just 36

$100s. Author image.

Figure 3. A run on a bank in New York City, June 1931. By the time Type 2 nationals were

produced in May 1933, the Great Depression had hit the nation with a vengeance, causing more

national banks to fail and curtailing the need for national bank notes. The Treasury Department

ended national bank note issuance in the summer of 1935, making the $100 Type 2 nationals a

short-lived type note. Courtesy FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images, Federal Reserve History.org

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

255

Basic Issue and Census Data

Only 37 banks issued $100 Type 2 notes. According to the Warns/Huntoon/Van Belkum

blue book, “The National Bank Note Issues of 1929-1935,” nine other national banks had $100

Type 2 notes printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) and delivered to the

Comptroller of the Currency Issue Division, but the notes were never sent to the banks and

ultimately canceled. Thirty-seven out of approximately 4,600 banks then issuing notes means less

than 1 percent of the national banks with circulation issued $100 Type 2 notes. The National

Currency Foundation (NCF) National Bank Note (NBN) Census lists 403 $100 Type 2 notes out

of 426,421 nationals in the census (as of June 27, 2022), roughly 1/10th of a percent of the recorded

notes.

Other current sources reinforce the scarcity of the $100 Type 2 notes. The PMG census

records 94 notes. The Heritage Auction Archives show less than 120 notes, compared to over 700

Lazy Deuces (with no attempt to weed out duplicate listings).

The $100 Type 2 nationals are offered so infrequently that it raised the question whether

they were always this scarce in the market, or if they were once more plentiful and have just gone

underground into tightly held collections. To pursue this question, there seemed no better way than

to conduct a survey of the thirty-eight Hickman & Oakes auction sales.

Hickman and Oakes

Hickman & Oakes was one of the top national bank note auction firm in the early days

when national bank note collecting took off. While the firm auctioned other currency as well, it

was in the national bank note arena that the firm gained most attention.

The H&O auctions were a

partnership of John Hickman and Dean

Oakes operating from Iowa City, Iowa.

H&O were the magnets for better

national material, and they reveled in

offering great material fresh from the

weeds. With offerings that included

Territorials, black charter $5 original

series notes, lazy deuces, and $100 Red

Seals, the array of nationals they

offered tantalized collectors.

Hickman and Oakes, together

and/or individually, were frequently

go-to sources when hoards of nationals

were discovered. In the early 1970’s,

Hickman, his earlier partner John

Waters, and collector Mort Melamed

purchased the famed Ella Overby

hoard from Starbuck, Minnesota.

Figure 5. The H&O catalogs were pamphlet size with black and

white photographs of the better lots. They long pre-dated the

glossy catalogs of today that come packed with high resolution

digital images, not to mention convenient online access. But the

H&O lot descriptions were filled with engaging lot descriptions,

well-informed commentary, and outright enthusiasm and

appreciation for the notes. Author copies.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

256

Hickman and Oakes bought the hoard of large size nationals that surfaced from charter

3939, The First National Bank of Wood River, Nebraska, virtually in their own backyard given

their Iowa City location. Before the H&O partnership, Oakes and his coin shop partner Don Jensen

acquired notes from the famed Oat Bin Hoard of old currency, including dozens of Original Series

and Series of 1875 nationals.

H&O conducted thirty-eight sales from 1976 to 1989. Sale No. 1 featured two key

collection of nationals, one by state seals and one by state capitals, popular pursuits at the time.

Fabulous notes, including two Alaska’s and the Series 1882 FNB of Tallahassee $100 Brown

Back, were sold in page after page. H&O was the annual auctioneer at a half dozen or so early

Memphis paper money shows, with the sales always bringing excitement.

September 1989, the 38th Sale, was the last H&O auction. The sale highlighted the Del

Bertschy collection of Wisconsin national bank notes. The catalog announced it would be the last

H&O sale. John Hickman went on to hold 19 sales under the Hickman Auctions name with his son

Rick, and Dean Oakes continued his longstanding separate business offering fixed price lists to a

large following of collectors of U.S. currency, large and small.

The H&O $100 Type 2 Survey Results

Despite over 10,000 lots sold in 38 sales, $100 Type 2 notes were only offered 24 times in

the H&O sales. In contrast, H&O offered 77 Lazy Deuces. Table 1 offers a comparison of how

many $100 Type 2 notes were sold vs. a selection of other highly sought-after national types. More

large size early-series $100 bills (Original, 1875, and 1882 series combined) were offered by H&O

than $100 Type 2 notes.

While cataloger bias can skew the offerings of certain notes, I don’t believe that is a

material factor in the Table 1 comparisons. H&O were a major market-maker for nationals at the

time, and both consignors and H&O themselves were financially motivated to offer good notes for

sale.

There is every indication from their lot descriptions that H&O was eager to offer a better-

type national like a $100 Type 2, regardless of condition. There is no indication any $100 Type 2

notes were omitted from sales due to space or other elective limitations.

Table 1. Hickman and Oakes Auctions

Sales Frequency by Selected Type

1976 to 1989*

Type of Note

Number of

Lots

Alaska Nationals - Large & Small 15

Lazy Deuces - Original & 1875 Series 77

$100 National - Original, 1875, and 1882 Series 39

$100 National - 1902 Red Seals 12

$100 National - Series 1929 Type 2 24

*omits Sale 34, full data unavailable, but no $100T2 were included

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

257

Table 2 shows the H&O $100 Type 2 notes offered in the 38 sales. A total of 24 lots were

offered over 14 years, comprising 22 different notes. Table 2 is a delight to peruse, and several

notable things jump out.

The first observation is that in the early days of nationals, these notes were modestly priced.

Most sold in the $200 range, slightly less for the more common the Bank of America and Live

Stock National Bank notes, and slightly more for the scarcer banks. And these are prices for notes

that were $100 face value. The purchasers were not risking a lot of money on their acquisitions!

Even the unique Allenhurst NJ note brought only $308 in 1985. Of course, in those days, issue and

census information was in its infancy, and bidders would not know if a given lot was merely the

first of several notes to come along. In the case of the Allenhurst note, it is now thirty-seven years

later and the note is still unique.

None of the $100 Type 2 lots brought big money until H&O Sale No. 28, the 1985

Memphis auction. There, the unique (and still unique) charter 11312, FNB of Lawrence County at

Walnut Ridge, Arkansas note (see Figure 6), sold for $1,150. Hickman’s lot description says it

all:

Lot 362. “Talk about a miracle of survival! This note, from the only bank in

Arkansas that issued this rare type, and one of only 72 notes placed in circulation,

turned up in Montana in 1982. The random survival of a well circulated note as

rare as this one is much more exciting than a note put away when it was issued.

Signatures of J.E. Krone and J.H. Myers, and light rust marks, as seen in photo.

A note can’t get much rarer than this, certainly not a 1929 note. Sure to be an

exciting lot and to be worth whatever it brings, which will surely be in excess of

$500.”

For aficionados of bank officers, J. E. Krone’s signature as cashier on the Walnut Ridge note is a

puzzle. Per the Rand McNally banker’s directories of July 1933 and the first 1934 issue, which

Figure 6. This is the only recorded $100 Type 2 note from this small issuing

Arkansas bank. Just twelve sheets totaling 72 notes were issued in this small town

of roughly 2,000 people in 1930. This note was the single highest-priced $100

Type 2 note sold in any H&O sale. Image courtesy Heritage Auctions.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

258

span the December 6, 1933 delivery date of the notes, the cashier in 1933 was L. B. Sharp (1933)

and in 1934 it was E. L. Moore (1934). Pollock’s database of bank officers agrees. Krone is also

unlisted in the bank officer search on the SPMC Banks & Bankers (1782-1935) database, but he

is listed as vice president in the 1933 and 1934 Rand McNally directories. The bank existed since

1919 without issuing notes, and in 1933 it transitioned to its second title, changing from the First

National Bank of Black Rock, Arkansas, to The First National Bank of Lawrence County at Walnut

Ridge, Arkansas. The two locations were barely nine miles apart, both in Lawrence County.

Perhaps Krone functioned as both VP and cashier during the transition period before new cashier

Moore arrived. Whatever the reason, it is Krone’s signature as cashier on the sole known note from

the bank.

Table 2 Census of Hickman & Oakes Lot Listings

for Series 1929 $100 Type 2 Notes

24 lots representing 22 notes

Sale Charter Catalog Price

No. Date Lot No. Bank, Location, and Serial Number if Available Grade Realized

2 4/11/1977 18 13044 Bank of America, San Francisco, CA XF 179$

10 4/10/1980 352 4295 FNB of New Braunfels, TX S/N A001078 VF 550$

11 9/24/1980 23 13044 Bank of America, San Francisco, CA VF 150$ *

16 3/24/1982 51 13674 Live Stock NB of Chicago, IL F+ 180$

17 6/18/1982 106 13044 Bank of America, San Francisco, CA AVF 160$

18 11/30/1982 19 13044 Bank of America, San Francisco, CA F+ 125$

74 13674 Live Stock NB of Chicago, IL F+ 121$

244 10865 Winona National and Savings Bank, MN S/N A000102 VG 200$

484 14219 NB & Trust Company of Erie, PA AVF 225$

570 13743 Mercantile NB at Dallas, TX VG 200$

19 3/30/1983 302 14219 NB & Trust Company of Erie, PA S/N A000314 AVF 242$

20 6/29/1983 11 13044 Bank of America, San Francisco, CA VG 150$ *

23 3/27/1984 38 13674 Live Stock NB of Chicago, IL VG/F 205$ *

25 10/30/1984 264 3913 Exchange NB of Colorado Springs, CO VF 250$ *

27 3/27/1985 218 12891 Allenhurst NB and Trust Co., NJ S/N A000018 VG-F 308$

28 6/15/1985 362 11313 FNB of Lawrence Cty at Walnut Ridge, AR S/N A00056 VG 1,150$

374 13044 Bank of America, San Francisco, CA XF 190$

29 11/16/1985 1317 4295 FNB of New Braunfels, TX S/N A001078 VF 550$ *

31 6/25/1986 52 13759 American NB at Indianapolis, IN F-VF 304$

32 11/14/1986 163 11313 FNB of Lawrence Cty at Walnut Ridge, AR S/N A00056 VG 1,418$

724 14219 NB & Trust Company of Erie, PA VF 300$ *

793 4070 City NB of Bryan, TX S/N A000021 XF "sev. hundred"*

35 6/25/1988 82 13674 Live Stock NB of Chicago, IL VF 275$

225 10865 Winona National and Savings Bank, MN S/N A000005 VF+ 750$

Notes: 1) bolded lot numbers indicate lots with photographs

2) *indicates the lot estimate is shown where the price realized was unavailable

3) the two notes sold twice were the Walnut Ridge AR note and the New Braunfels TX note.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

259

Another takeaway from Table 2 is that almost half (10 of 22) the Type 2’s sold by H&O

were from the two most common banks, charter 13044 Bank of America National Trust and

Savings of San Francisco, and charter 13674 The Live Stock National Bank of Chicago. That

relative prevalence has continued over time, with those two banks now accounting for 57 percent

of the Type 2 $100’s in the current NBN Census.

The $100 Type 2 notes were highly prized despite most offerings being well circulated

grades. Certainly H&O sales were of an era when notes were judged primarily on their rarity and

the wonder of their survival against long odds. Collectors today striving for high grade examples

of $100 Type 2 notes will have only a few from which to choose. Using the PMG census as a

sample, only four of 94 PMG-grade $100 Type 2 notes are uncirculated, and the NBN Census

shows about a dozen uncirculated notes.

Despite being issued by just 37 banks and in small numbers, the $100 Type 2 notes have a

surprising variety to them. With a territorial issue, a major titling error, notes with famous

pedigrees, and plenty of interesting back stories, a lot of numismatic interest is packed into a few

scarce notes.

$100 Type 2 Rarities Abound

Eight of the 37 $100 Type 2 issuing banks have no known notes. Another 12 banks have

only one or two known notes. See Table 3 for a complete list of the $100 Type 2 issuing banks

and current census.

Over half the 37 banks are represented by zero to two notes, so the most collectible notes

come from less than half the issuing banks, and even most of those are few and far between.

The $100 Type 2 notes from Maryland are, so far, an impossibility to complete. Notes are

known from only two of the three issuing banks. See Figure 7. Maryland had three $100 Type 2

banks that issued a combined total of 93 notes. Not sheets, notes! Maryland boasts the single rarest

$100 Type 2 issuer, Ch. 5471, the FNB of Southern Maryland of Upper Marlboro. The bank issued

just 13 $100 Type 2 notes. None are known.

Figure 7. No national

banks in Baltimore,

Maryland’s largest city

and its largest commercial

center of the national era,

issued $100 Type 2

nationals, but these two

small banks on the eastern

shore did. Each of these

banks has two surviving

notes in the current

census. The issuing

numbers are astoundingly

low: the Salisbury bank

issued 45 notes and the

Cambridge bank issued

35. Images courtesy Fred

Maples and Heritage

Auctions

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

260

Table 3 The 37 Banks Issuing $100 Type 2 National Bank Notes

in Ascending Order Based on Notes Issued

Notes Notes

Charter Bank State Issued in Census

5471 FNB of Southern Maryland of Upper Marlboro MD 13 0

3990 NB of Coatsville PA 24 0

5880 Farmers and Merchants NB of Cambridge MD 35 2

5118 Northampton NB of Easton PA 36 1

14236 Central NB of McKinney TX 36 0

3250 Salisbury NB MD 45 2

13703 Birmingham NB MI 48 0

4260 Citizens NB of Covington KY 56 2

14021 FNB in Boulder CO 60 1

4695 FNB of Brownwood TX 67 2

11312 FNB of Lawrence County at Walnut Ridge AR 72 1

12997 Franklin Square NB NY 72 0

12311 FNB of Ferrum VA 72 1

2154 FNB of Belleville IL 88 0

12891 Allenhurst NB and Trust Company NJ 132 1

10865 Winona National and Savings Bank MN 144 10

14285 Mount Olive NB IL 250 7

13775 Citizen NB of Hampton VA 252 0

13893 Edgewater NB NJ 270 2

13758 NB of Grand Rapids MI 288 4

13676 Witchita NB of Witchita Falls TX 384 5

94 FNB of Port Jervis NY 636 2

5550 Bishop NB of Hawaii HI 682 3

13759 American NB at Indianapolis IN 696 8

9353 Houston NB TX 713 5

3913 Exchange NB of Colorado Springs CO 733 10

13648 Commercial NB in Shreveport LA 751 7

4070 City NB of Bryan TX 889 11

14219 NB and Trust Company of Erie PA 1,017 22

13688 Hibernia NB in New Orleans LA 1,111 10

4295 FNB of New Braunfels TX 1,141 13

13743 Mercantile NB at Dallas TX 1,234 9

13901 Rhode Island Hospital NB of Providence RI 1,611 20

12186 Republic NB and Trust Company of Dallas TX 1,995 10

13681 NB of Commerce in Memphis TN 3,600 0

13674 Live Stock NB of Chicago IL 5,856 61

13044 Bank of America Nat. Trust and Savings Assoc. CA 41,112 172

TOTAL 66,221 404

Notes: 1) Banks canceling their entire $100T2 note deliveries omitted from this table.

2) Notes Issued data from Kelly 6th Ed. (2008)

3) Census numbers from NBN Census, courtesy the National Currency Foundation.

Ch. 13743 count adjusted upward by 1 for author's note not yet in online census.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

261

Some $100 Type 2 notes come with illustrious pedigrees. The Winona National and

Savings Bank, Winona, Minnesota, has 10 notes known today, a healthy number given its small

issue of 144 notes. One of those is the serial number 5 note, ex Amon Carter, among others. H&O

sold the note in their 1988 Memphis Sale No. 35. See Figure 8. Another Winona prize is the

uncirculated serial number 7 note sold in 2018 in the Davidson collection of $100 type notes.

Hawaii Territorials

The $100 Phantoms of Memphis

One of the most prolific issuers of $100 Type 2 notes, in theory at least, was charter 13681,

the National Bank of Commerce in Memphis, Tennessee. Per Kelly, the bank issued 3,600 $100

Type 2s, exceeded in number by only the Bank of America and the Live Stock National Bank

issues. Yet, not a single National Bank of Commerce $100 is known today. There are four $50

Type 2 notes reported out of 14,760 issued, but no hundreds. What is going on?

The National Bank of Commerce is an interesting case study in what was meant by national

bank circulation. The bank was organized on April 29, 1933. It was well capitalized and purchased

$1 million in 2 percent bonds carrying the circulation privilege.

The Comptroller’s Currency and Bond ledgers show clearly the BEP delivered 4,980 $100

Type 2 notes to the Comptroller’s vault on August 22, 1933 (along with $50 Type 2 stock). On

September 2, 1933, the Comptroller’s office sent the bank its million dollars in circulation,

consisting of 12,800 $50s and 3,600 $100s.

Yet, at the end of December 1933, when it came time to report its taxable circulation to the

Comptroller, the bank reported zero (Pollock 2021). Next year, at the end of December 1934, the

bank again reported zero circulation. Since $50 Type 2 notes from the bank’s stock are known to

collectors, what was the bank doing?

Pulling the Currency and Bond Ledger from the National Archives, the story became clear.

Sure enough, the $1 million in notes were sent to the bank September 2, 1933, but the notes were

never released, hence the bank could justifiably report no circulation each year.

Examination of the bank’s redemption ledger from 1933 onward shows not a single note

of any kind was ever redeemed. The notes never left the bank before July 17, 1935 when the bank’s

bonds were redeemed per Treasury’s bond call that ended national bank circulation.

Figure 8. This Winona National and Savings Bank note was the last $100 Type 2

note H&O sold at auction. It was Lot 225 in Sale 35, the Memphis sale of June

24-25, 1988. The note has had several illustrious owners, and passed through the

hands of H&O, Peter Huntoon, and Lyn Knight. It was part of the serial number 5

collections of Amon Carter and later Dick Erett. Image courtesy Lyn Knight.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

262

The Kelly reference shows the 3,600 $100 Type 2’s delivered to the bank, and showed the

Out in 1935 circulation to be $1 million. But, what was hidden was the fact the bank never released

the notes during the national era. They earned interest on their robust $1 million in bonds but

avoided paying circulation taxes on the notes.

Once the bonds were called and the proceeds had been deposited with Treasury to end the

bank’s circulation tax liability, the notes became ordinary vault cash. We know the $50s were

released, but what happened to the $100s is unknown. They are true phantoms, likely redeemed

87 years ago.

American National Bank at Indianapolis Errors

In terms of offering something for everyone, the small pool of $100 Type 2 notes even

offers a title error. See Figure 9. A total of 816 $100s were printed by the Bureau of Engraving

and Printing (BEP) for charter 13759 of Indianapolis, sent to the Comptroller’s office in three

deliveries.

The first BEP delivery to the bank was October 19, 1933, consisting of 30 sheets, serials 1

through 180. The notes entered circulation. The second BEP delivery to the Comptroller’s Issue

Division was February 14, 1934, serials 181 to 634. After delivery of much of the stock to the

bank, someone finally noticed the title of the bank was wrong on the notes! The notes said

American National Bank of Indianapolis [emphasis added]. The bank’s actual title was American

National Bank at Indianapolis. The remaining notes with the incorrect title were canceled,

consisting of serial numbers 505-624. The BEP then delivered, on March 27, 1934, serials 625 to

816 with the correct bank title. When the dust settled, 696 notes, counting both titles, were issued

to the bank. Ambitious numismatists can try to beat the odds and collect one of each title.

Figure 9. The only title

error in the $100 Type 2

series belongs to charter

13759. The top note is the

error, the bottom note

shows the correct “at”

Indianapolis title phrasing.

Images courtesy Heritage

Auctions.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

263

The Mount Olive National Bank

The Memphis situation is an interesting contrast with another $100 Type 2 issuer, the late-

opening charter 14285, The Mount Olive National Bank, Mount Olive, Illinois. The bank was

chartered in October 1934, but took its time purchasing its circulation bonds. The BEP got notes

ready early, printing $100 Type 2 notes only, and sent two deliveries to the Comptroller’s vault,

one in late December 1934 and one in late January 1935. But the Comptroller sent no notes to the

bank, for the plain reason the bank had no bonds on deposit.

Finally, on February 23, 1935, the Mount Olive National purchased $25,000 in bonds and

deposited them with the Comptroller. The very same day the first of five $5,000 currency

shipments were sent to the bank, the last being sent March 6, 1935, ending in serial number

A000250.

All this work was to be for naught. On March 9, 1935, Treasury Secretary Henry

Morgenthau Jr. released a press statement saying the 2 percent Consols backing national bank note

circulation would be called on for redemption on July 1, 1935, and the 2 percent Panama Canal

bonds would be called August 1, 1935. The bankers at Mount Olive National had just three days

to enjoy their stack of 250 $100 bills before learning the notes would be the last, and only, of their

kind.

The bankers didn’t wait for Treasury’s July bond call to get out of the circulation business.

On April 6, 1935, they deposited lawful money with the Comptroller to clear their tax liability for

the notes. The notes were now vault cash. With seven $100 Type 2 notes known, the evidence

points to the bank taking its modest stack of 250 notes and eventually circulating them over the

counter rather than going to the effort of redeeming them.

Hawaii Territorials

Charter 5550, the Bishop National Bank of Hawaii at Honolulu, issued 682 $100 Type 2

notes, the only territorials of the type. Only 3 are known, a number that hasn’t changed in a decade.

Hawaii national bank notes were subject to the World War II June 25, 1942, order from Territorial

Governor Joseph B. Poindexter to exchange regular currency for Treasury’s specially marked

Hawaii overprint notes. The small issue of $100 Type 2s, together with the mandatory exchange

of notes during the war, makes the survival of three notes all the more amazing. See Figure 1.

Observations

The review of the old H&O auction sales answered the initial question that prompted this

article, namely whether the $100 Type 2 notes used to be more common and have just dried up in

today’s market or whether they were always scarce. The answer is clearly the latter. Beyond the

several banks profiled in this article, all the $100 Type 2 issuing banks listed on Table 3 are worth

the pursuit.

Low prices are not the norm anymore, particularly for true VF and better notes in original,

undamaged condition. Nice original notes fine and better see competitive bids and solid prices.

Issued in small numbers to begin with, and facing withering economic conditions and

almost immediate attrition, the 400+ $100 Type 2 nationals that have surfaced for collectors today

defied the odds to be here.

Acknowledgments

This article utilized several of the high quality online resources our hobby has been making

available, among them the Society for Paper Money Collector spmc.org website and its Bank Note

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

264

History Project databases, the National Currency Foundation and its National Bank Note Census,

the joint NCF/SPMC online publication of the Huntoon-Shiva Encyclopedia of U.S. National Bank

Notes, and the Newman Numismatic Portal at Washington University at St. Louis. The Heritage

Auctions, Stack’s Bowers, and Knight archives continue to be a benefit for the hobby. Fred

Maples, Peter Huntoon, and Jim Simek provided timely assistance as well.

Sources

Bowers, Q. David. American Coin Treasures and Hoards. Chapter 17, pp. 343-350. Bowers and Merena Galleries, Wolfeboro,

NH. (1997).

Comptroller of the Currency, Annual Reports, 1929-1934. 1929 pp. 30-31; 1933 p. 2; 1934 p. 63. Washington, DC (1929-1934).

Comptroller of the Currency, National Currency and Bond Ledgers. Record Group 101, U.S. National Archives, Archives II,

College Park, Maryland. (1863-1935).

Heritage Auction Archives. Heritage Auctions, Dallas TX. ha.com (2022).

Hickman, John, and Dean Oakes, Hickman and Oakes Auction Sales 1-38, Iowa City, IA. (1976-1989).

Huntoon, Peter, Lee Lofthus and James Simek, “Series of 1929 Type 2 Serial Numbers,” Paper Money, July/August 2011, pp. 244-

249. Vol. L, Whole No. 274, Society of Paper Money Collectors, spmc.org

Huntoon, Peter, and Jamie Yakes, “Glass-Borah Amendment of 1932 spiked Series of 1929 National Bank Note Circulation by a

Third,” Paper Money, May/June 2022, pp. 198-203,Vol. LXI, Whole No. 339, Society of Paper Money Collectors,

spmc.org

Huntoon-Shiva Encyclopedia of U.S. National Bank Notes, SPMC Content (accessed July 13, 2022). Chapter G4, Serial Numbering

on Series of 1929 National Bank Notes, version of June 4, 2022. (2022). Spmc.org

Kelly, Don C. National Bank Notes, A Guide with Prices, Sixth Edition. Oxford, OH. The Paper Money Institute. (2008).

Lofthus, Lee, “Hawaiian Series Currency,” Paper Money, January/February 2006, pp. 6-23, Vol LXI, No. 1, Whole No. 337,

Society of Paper Money Collectors, spmc.org

Lofthus, Lee, “Louis Van Belkum’s ‘No Circulation’ National Banks Revisited,” Paper Money, September/October 2006, pp. 345-

358,Vol. XLV, No. 5, Whole No. 245, Society of Paper Money Collectors, spmc.org

Maples, J. Fred. Maryland Paper Money, An Illustrated History, 1964-1935, JFM Numismatics, Montgomery Village, MD, (2015).

National Currency Foundation, National Bank Note Census. National Currency Foundation, New York, NY.

nationalcurrencyfoundation.org (2022).

Paper Money Guarantee Inc. PMG Population Report, PMG, Sarasota, FL. pmgnotes.com (2022).

Pollock, Andrew, “Compilation by Year of National Bank President’s, Cashiers, Total Resources, and Circulations, 1863-1935.”

Newman Numismatic Portal at Washington University, St. Louis, MO. (2021).

Rand McNally, “Bankers Directory, The Bankers Blue Book,” p. 93. July 1933 edition.

Rand McNally & Co, New York, Chicago, San Francisco. (1933). Via Fraser, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Fraser.stlouisfed.org.

Rand McNally, “Bankers Directory, The Bankers Blue Book,” p. 111. March 1934 edition. Rand McNally & Co, New York,

Chicago, San Francisco. (1934). Via Fraser, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Fraser.stlouisfed.org.

Rare National Currency, “Hickman and Oakes Auctions.” August 13, 2011. Rarenationalcurrency.com

Society of Paper Money Collectors, The Bank Note History Project, Banks & Bankers Database (1782-1935). spmc.org (2022).

U.S. Treasury, Press Service No. 4-47, “Release, Morning Newspapers, Monday, March 11, 1935.” [Secretary Morgenthau

announces call of two per cent Consols for redemption on July 1, 1935 and two per cent Panama Canal bonds for

redemption on August 1, 1935]. March 9, 1935. Treasury Department, Washington. (1935).

Warns, Melvin, Peter Huntoon, and Louis Van Belkum. The National Bank Note Issues of 1929-1935, Second Edition. Society of

Paper Money Collectors. Chicago, IL: Printed by Hewitt Brothers, (1973).

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

265

$20 Series of 1880 Legal Tender

Serial Number

Color Change

Lee Lofthus found correspondence in Bureau of the Public Debt documents in the National

Archives that fully explain a little-noted variety on the last of the Series of 1880 $20 legal tender

notes. Specifically, the serial numbers on the Teehee-Burke and Elliott-White notes were changed

from blue to red. A number of factors came into play to cause this.

Series of 1880 Legal Tender Notes

The 1880 legal tender series encompassed every denomination from $1 to $1,000. The

series was printed from fiscal year 1880 through 1926. However, the Treasury ceased ordering

Series of 1880 $1s and $2s at the end of FY 1896 and $5s at the end of FY 1900. Production of all

the other legal tender denominations in the series except the $20s and $1000s ceased by FY 1903

as the Treasury assigned the use of low denomination Treasury currency to silver certificates and

higher denominations to gold certificates.

The Treasury was adopting new designs for most classes of currency beginning at the turn

of the century. $10 legal tender production continued, but came out in the form of the redesigned

Series of 1901 bison issues. $5 legal tender production resumed after a few years in the form of

Series of 1907 woodchopper notes, and, in the long haul, $1 and $2 production finally resumed in

the form of Series of 1917 notes.

The only Series of 1880 legal tender production that occurred after FY 1903 consisted of

$20s and $1000s as follows (BEP, yearly).

FY Sheets FY Sheets

$20 1909 101,000 $1000 1904 8,000

1910 102,000 1909 5,000

1918 100,000

1922 688,000

1926 457,000

The Paper

Column

Peter Huntoon

Lee Lofthus

Figure 1. The only Series of 1880 Legal Tender notes with red Treasury serial

numbers are Teehee-Burke and Elliott-White $20s. Heritage Auction archives photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

266

Sealing

In 1885, the sealing of Treasury currency was transferred from the Bureau of Engraving

and Printing to the Treasurer’s office as a security measure (Huntoon and Murray, 2019, 2020).

The idea was that sealing monetized the notes, so it seemed appropriate to do it within the Treasury

building. This practice meant that the BEP printed the serial numbers and the Treasurer’s office

printed the seals on the notes.

Things changed in 1910. The BEP installed a new generation of numbering presses that

were capable of numbering and sealing the sheets, separating the sheets into individual notes, and

collating them in serial number order. At this point, Congress ordered that sealing be returned to

the BEP. A major incentive was that both numbering and sealing could be carried out with one

pass through the new Harris presses at great savings (Huntoon and Lofthus, 2014).

Serial Number Colors

The BEP had been using blue ink to number the 1880 LTs and the Treasurer was using red

ink for the seals before sealing was returned to the BEP. The colors didn’t matter because

processing involved two different press runs in different buildings. Using the different colors made

little sense after sealing was returned to the BEP where both the numbers and seals were to be

printed on the same machine.

The Treasury lodged an order for 100,000 sheets worth of $20 LTs in late 1918, the first

such order since FY 1910. The $20 LTs had not been redesigned so the order would come out in

the form of Series of 1880 notes.

BEP director James L. Wilmeth sent the following memo to Secretary of the Treasury

William McAdoo on April 12, 1918 (BPD, 1917-1942).

Reference to order now in hand for printing $20 United States notes, series 1880, I beg to

state that the last time these notes were printed the number was printed in blue by this Bureau

and the seal was printed in red at the Division of Issue in the Treasury Department building. Since

this Bureau has taken over the sealing as well as the numbering of the notes, all of the other

denomination of United States notes have had their series changed and have both number and

seal printed in red. It is suggested, therefore, inasmuch as all of the other denominations are so

printed that this Bureau be authorized to print the number and seal on the $20 denomination also

in red ink. This is an especially opportune time to begin this change for the reason that on the

notes now to be issued, both the facsimile signatures of the Treasurer and the Register have been

changed.

Figure 2. The Series of 1880 Legal Tender notes printed before 1918 had blue

Treasury serial numbers. Heritage Auction archives photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

267

The response from the Treasury was immediate in the form of a letter from Assistant

Secretary of the Treasury James H. Moyle dated April 13th.

By direction of the Secretary the suggestion contained in your communication of the

12th instant is approved and you are hereby authorized to print the number and seal on

the twenty dollar denomination United States notes in red.

Thus, the 1918 printing of 100,000 sheets of Teehee-Burke $20 Series of 1880 notes

sported red Treasury serial numbers. The Treasury ordered two more printings of LT $20s, one in FY

1922 and the second in FY 1926. These also were Series of 1880 notes with red Treasury serials

but Elliot-White Treasury signatures.

As fate would have it, these three $20 orders were the only Series of 1880 notes numbered

and sealed after the Harris presses came on line in 1910. Consequently, they are the only Series of

1880 notes to bear red Treasury serial numbers.

To mark the occasion, numbering of the Teehee-Burke $20s commenced with serial A1A

with the 1918 order. The $20s sealed previously in the Treasurer’s office had blue serials that had

been printed at the BEP with a D-prefix.

Things are Interconnected

The change to red Treasury serial numbers on the Series of 1880 $20 owes its origin to the

introduction of the Harris numbering, sealing, cutting and collating presses at the Bureau of

Engraving and Printing. Because these machines overprinted both the serial numbers and seals, it

made practical sense that both be the same color.

The fact that the Harris presses were designed to overprint both of those features in one

pass caused the entire Treasury apparatus and its Congressional overseers to reevaluate the

necessity of having the seals applied in a separate printing step within the Treasury building. The

BEP had sufficient security protocols in place that it had gained the trust of Congress that it could

add the seals—which technically monetized the notes—and deliver them to the Treasury without

defalcation.

The Treasury was carrying out a program to modernize the look of all of its Treasury

currency series, a slow process begun at the turn of the 20th Century. The redesigns led to the

advent of new series. Simultaneously, the Treasury officials were attempting to reduce the

multitude of different looking notes in circulation by exclusively assigning specific denominations to

one or the other of the three classes of Treasury currency then in use. No priority was given to the

redesign of the Series of 1880 $20 and $1000 legal tender denominations because the plan was to

allocate those denominations to gold certificates. Thus, when belated orders came down from

Treasury for more of them after the turn of the century, the plates available to print them were

those in the Series of 1880.

The Harris presses came on-line in 1910. When orders came from Treasury for more $20

legal tender notes in FY 1918, and again in FYs 1922 and 1926, the notes came out as last-gasp

Series of 1880 notes. Being the last notes in the series, and the only notes in the series overprinted on

Harris presses, they came out with distinctive red Treasury serial numbers.

Thus, the stars had aligned just right in order for the Teehee-Burke and Elliott-White $20

Series of 1880 legal tenders to carry red Treasury serial numbers.

Sources

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, yearly, Annual Reports of the Director of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing: Government

Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Bureau of the Public Debt, 1917-1942, April 12-13, 1918 correspondence between BEP Director James Wilmeth and Assistant

Secretary of the Treasury J. H. Moyle: Files related to Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Record Group 53, Entry UD-

UP 9,ox 8, files C550-C610: U. S. National Archives, College Park, MD.

Huntoon, Peter, and Lee Lofthus, Nov-Dec 2014, The birth of star notes, the back story: Paper Money, v. 53, p. 400- 411.

Huntoon, Peter, and Doug Murray, Sep-Oct 2019, Treasury sealing assigned to Treasurer’s office in 1885: Paper Money, v.

58, p. 328-336.

Huntoon, Peter and Doug Murray, May-Jun 2020, Treasury seal varieties when sealing was carried out at the Treasurer’s

office between 1885 and 1910: Paper Money, v. 59, p. 179-187.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

268

The Civil War Stamp Money of Confederate Mobile, Alabama

by Steve Feller

On January 11, 1861, Alabama seceded from the United States and on February 4, 1861, the state joined the

Confederate States and the new government’s organizational meeting was held in Montgomery [1]. By April the

American Civil War began and a terrible struggle had begun. During the ensuing war the Southern States issued

thousands of different kinds of paper money.

Initially, United States postage continued to operate in these states and a mutual agreement to separate Southern

post offices was put into place setting June 1, 1861, as the formal date of separation. At that point several post offices

issued their own Confederate provisional stamps and markings until uniform Confederate postage stamps were

released in the fall of 1861. The most common of these provisional adhesive stamps were produced in New Orleans

and it wasn’t long before other post offices followed suit. This included Mobile, AL.

Figure 1a: A montage of Confederate provisional stamps from Mobile, AL.

Figure 1b: Two- and five-cent

Confederate provisional stamps from

Mobile, AL.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

269

All Confederate provisional stamps are at least scarce. Rarer still by far are the small-change money issues of

these respective post offices [2]. Sometimes just a few notes are known from a particular post office. This article

will focus on the handful of surviving small change chits from Mobile, Alabama.

Here are examples of post office scrip from New Orleans and Mobile:

Figure 2: a. Civil War Stamp Money for one-cent from New Orleans. b. Close up and color enhanced image of the one-cent note with

New Orleans Postmaster J.L. Riddell’s impressed name. Note that Riddell’s daughter signed the note as well as a postage clerk. Much

more detail on New Orleans stamp money may be found in reference [3].

According to The New Dietz Confederate States Catalog and Handbook [4], published in 1986, Owen was the

Assistant Postmaster in Mobile. There is an image of the one-cent scrip in this source that has Owen’s signature with

a slightly different signature orientation than the note shown here. Also, a three-cent note is mentioned as being

printed in black on white paper.

Fig. 3: Three unissued Civil War stamp

money chits from New Orleans.

Fig 4. a, b, and c. One-cent stamp

money from Mobile, AL. Note that

it was signed by Owen.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

270

Fig. 5: Close-up of the back of the one-cent note.

The date is printed twice and is likely NOV 24.

Fig. 6: a, b, c, and d: One-cent and three-cent post office scrip from the Mobile Post Office.

The one-cent note in Fig. 6 seems to be printed on scrap paper having to do with an election and taxes. Once

again the scrip was dated by the post office’s date mark. The dates are December 7 and October 11. They are without

year, but it seems likely that they were used in 1861-62 as a way to give small change as the Confederate period

began. Small change disappeared from circulation by the fall of 1861. By the fall of 1862 and especially later small

change notes like this were hardly worth printing and yet it was at some post offices, although in somewhat larger

denominations [2]! The value of a Confederate dollar in gold fell during the war and was [5]:

December 1861: $0.83

December 1862: $0.33

December 1863: $0.05

December 1864: $0.026

Thus, by December 1864 a one-cent chit was worth $0.00026 in gold, or 3846 chits was valued at a gold dollar!

Today, it is decidedly a different story.

I present comments from The Organization of the Confederate Post Office at Montgomery by Peter Brannon

[6]:

After secession and before the organization of the Confederate government, the independent states used United

States stamps and stamped covers, and upon the creation of the Confederate Post Office Department the United

States and the Confederate States agreed that postmasters appointed before secession should remit as of June 1,

1861, all monies in hand on that day to Washington City. This arrangement produced many interesting postmarks

and covers. The Confederate postmasters were embarrassed in the sale of postage, and many devised temporary

provisional facilities. Others used pen cancellations and manuscript postmarks. The absence of small change caused

further embarrassments and most postmasters were required to open charge accounts with their patrons.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

271

Other post offices issued chits. These are dated throughout the war but mainly earlier in the war. Thus, it is not

possible to state for sure what year these were printed.

The Mobile, AL post office was located in the customs house shown below in Figures 7 a, b, and c. It was

designed by noted architect Ammi Burnham Young (June 19, 1798 – March 14, 1874); he was the first Supervising

Architect of the United States Treasury Department. The building was completed in 1856 and removed in 1963.

The magazine Mobile Bay gave this description of the building [7]:

Architect Ammi Young designed this Italianate and classical revival masterpiece. Located downtown (where the

RSA-Bank Trust Building is now), it was built like a fort — granite blocks laid with inter-locking joints all set on a

foundation of solid clay and 12-inch-thick heart pine. Not surprisingly, it cost a whopping $360,000. The building

was notable for its disciplined form and pleasing eave brackets. Its demolition nearly bankrupted the company

hired for the job.

Fig.7: a) Plans, b) front and c) side views of the post office and customs house in Mobile that existed during the Civil War. Photos

from the Library of Congress. This is where the Mobile, AL Postmaster’s Provisionals stamps and small-change chits were issued.

The Postmaster of Mobile, AL during the Civil War was Lloyd Bowers. He was 37 when the Civil War began

in April 1861 and when he issued provisional stamps beginning in June or July1861.

Lloyd Bowers was born in Louisiana on March 11, 1824, and was married on June 11, 1846, to Louise Ann

Toulmin. This marriage produced six children. Descendants of the children survived until at least 1995. Lloyd died

May 18, 1891, and Louisa died September 17, 1903 [9].

No biographical information was found on Assistant Postmaster Owen.

Lloyd Bowers was born in Louisiana on March 11, 1824, and was married on June 11, 1846, to Louise Ann

Toulmin. This marriage produced six children. Descendants of the children survived until at least 1995. Lloyd died

May 18, 1891, and Louisa died September 17, 1903 [9].

No biographical information was found on Assistant Postmaster Owen.

These notes are certainly rare. They are not listed in numismatic sources such as Don Kelly’s Obsolete Paper

Money [10] or Walter Rosene, Jr’s, Alabama Obsolete Notes and Scrip [11], just the Dietz books on Confederate

Figure 8: Grave of Postmaster

Lloyd Bowers of Mobile, AL.

Figure 9 a and b: Close ups of Lloyd Bowers and wife Louisa Toulmin gravestones. The

graves are in the Magnolia Cemetery in Mobile. Images are from Find a Grave [8].

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2023 * Whole No. 346

272

stamps lists them, as mentioned earlier. Do any readers have examples of these scrip? If so, please send images to

sfeller@coe.edu.

In summary, here is a table with up to five scrip notes that are known today of the Mobile Post Office:

Denomination Size Color Date

One cent 49mm x27mm Black on white cardboard Nov(?) 24, 1861 or 1862?

49mm x27mm Black on white cardboard Dec 7, 1861 or 1862?

Black on white* Back not shown

Three cents 49mm x26mm Black on orange cardboard Oct 11, 1861 or 1862?

Black on white* Back not shown

*As listed in [4].

Mobile was a major port for the Confederacy. However, the North, under

Admiral Farragut effectively blockaded the city (See Fig. 10.). Mobile

surrendered to the Union on April 12, 1865, three days after General Robert E.

Lee surrendered.

References

[1]. Dates taken from Dates of State Secession and their Admission to the Confederacy provided by Patricia Kaufman from

https://www.trishkaufmann.com/resources-and-links from Independent State Mail and Confederate Use of U.S. Postage: How Secession

Occurred: Correcting the Record (La Posta Publications: Fredericksburg, VA) 2018.

[2]. Steve Feller, “Confederate Stamp Money Revisited,” Confederate Philatelist 65 (2) 15-33 (2020).

[3]. S.A. Feller, “The Notes of John Leonard Riddell, Postmaster of New Orleans.” Paper Money (2012) LI (3) (Whole Number 279) 163-168

(2012).