Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

Rare Postal Note from Sitka Alaska Surfaces--Kent Halland & Charles Surasky

1862-1863 Legal Tender Classification Chart--Peter Huntoon & Doug Murray.

3rd Issue Fractional Currency Errors (Part 2)--Rick Melamed

Uncoupled—Joe Boling & Fred Schwan

Origin of the Train Vignette on T-39 Confederate Notes--Marvin Ashmore & Michael McNeil

John Benjamin Burton--Charles Derby

United Cigar Stores Company Coupons--Loren Gatch

1917 $1 Fr. 37a Error--Peter Huntoon

Small Notes—Two $5 Master Plate Proofs

Membership Map

New SPMC Exhibit Program

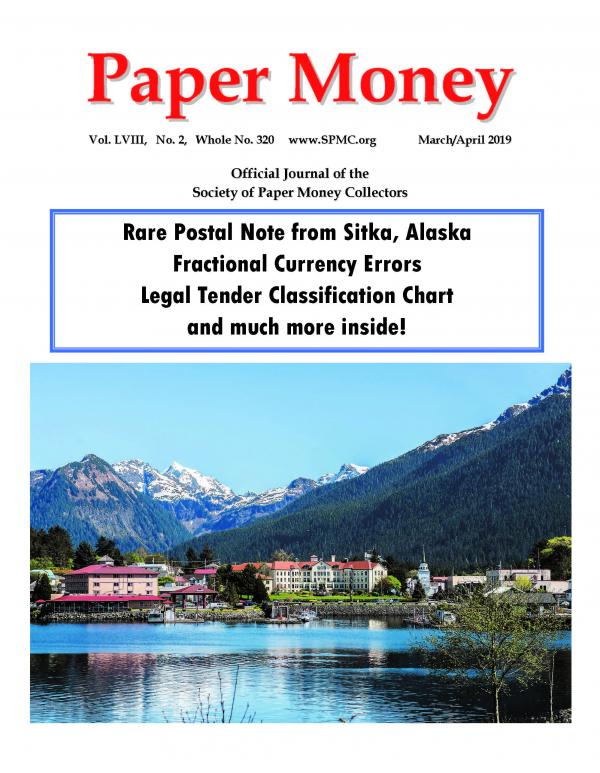

Rare Postal Note from Sitka, Alaska

Fractional Currency Errors

Legal Tender Classification Chart

and much more inside!

Paper Money

Vol. LVIII, No. 2, Whole No. 320 www.SPMC.org March/April 2019

Official Journal of the

Society of Paper Money Collectors

1231 E. Dyer Road, Suite 100, Santa Ana, CA 92705 • 949.253.0916

123 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10019 • 212.582.2580

Info@StacksBowers.com • StacksBowers.com

California • New York • New Hampshire • Hong Kong • Paris

SBG PM ANA2019AucSol 190130

America’s Oldest and Most Accomplished Rare Coin Auctioneer

Peter A. Treglia

LM #1195608

John M. Pack

LM # 5736

Peter A. Treglia

John M. Pack

Brad Ciociola

Peter A. Treglia Aris MaragoudakisJohn M. Pack Brad CiociolaManning Garrett

LEGENDARY COLLECTIONS | LEGENDARY RESULTS | A LEGENDARY AUCTION FIRM

Now Accepting Consignments to the

Stack’s Bowers Galleries Official Auction of the

ANA World’s Fair of Money®

Stack’s Bowers Galleries continues to realize strong prices for currency, as shown by these results from our recent

auctions. We are currently accepting consignments to our Official Auction of the 2019 ANA World’s Fair of Money

in Rosemont, Illinois. Whether you have an entire cabinet or just a few duplicates, the experts at Stack’s Bowers

Galleries are just a phone call away and ready to assist you in realizing top dollar for your currency.

Contact our currency specialists

to discuss opportunities for upcoming

auctions. They will be happy to assist

you every step of the way.

800.458.4646 West Coast Office

800.566.2580 East Coast Office

T-2. Confederate Currency.

1861 $500. PMG Very Fine 30.

Realized $39,950

Fr. 2220-F. 1928 $5000 Federal Reserve Note.

Atlanta. PCGS Very Fine 30 PPQ.

Realized $129,250

Deadwood, South Dakota. $10 1882 Brown Back.

Fr. 487. The American NB.

PCGS Very Fine 30 PPQ. Serial Number 1.

Realized $64,625

Fr. 202a. 1861 $50 Interest Bearing Note

PCGS Currency Very Fine 25.

Realized $1,020,000

Fr. 346d. 1880 $1000 Silver Certificate of Deposit.

PCGS Currency Very Fine 25.

Realized $1,020,000

Fr. 183c. 1863 $500 Legal Tender Note

PCGS Currency Very Choice New 64 PPQ.

Realized $900,000

Fr. 187b. 18803 $1000 Legal Tender Note

PCGS Currency Choice About New 55.

Realized $960,000

Ketchikan, Alaska. Small Size $5. Fr. 1800.

The First NB of Ketchikan. Charter #4983.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ*.

Realized $90,000

Auction: August 13-16, 2019 | Consign U.S. Currency by June 24, 2019

Fr. 379a. 1890 $1000 Treasury Note,

PCGS Currency About New 50.

Realized $2,040,000

Terms and Conditions

PAPER MONEY (USPS 00-3162) is published every

other month beginning in January by the Society of

Paper Money Collectors (SPMC), 711 Signal Mt. Rd

#197, Chattanooga, TN 37405. Periodical postage is

paid at Hanover, PA. Postmaster send address

changes to Secretary Jeff Brueggeman, 711 Signal

Mtn. Rd, #197, Chattanooga,TN 37405.

©Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc. 2014. All

rights reserved. Reproduction of any article in whole or

part withoutwrittenapproval is prohibited.

Individual copies of this issue of PAPER MONEY are

available from the secretary for $8 postpaid. Send

changes of address, inquiries concerning non - delivery

and requests for additional copies of this issue to the

secretary.

PAPER MONEY

Official Bimonthly Publication of

The Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc.

Vol. LVIII, No. 2 Whole No. 320 March/April 2019

ISSN 0031-1162

MANUSCRIPTS

Manuscripts not under consideration elsewhere and

publications for review should be sent to the Editor.

Accepted manuscripts will be published as soon as

possible, however publication in a specific issue

cannot be guaranteed. Include an SASE if

acknowledgement is desired. Opinions expressed by

authors do not necessarily reflect those of the SPMC.

Manuscripts should be submitted in WORD format via

email (smcbb@sbcglobal.net) or by sending memory

stick/disk to the editor. Scans should be grayscale or

color JPEGs at 300 dpi. Color illustrations may be

changed to grayscale at the discretion of the editor.

Do not send items of value. Manuscripts are

submitted with copyright release of the author to the

Editor for duplication and printing as needed.

ADVERTISING

Alladvertising onspaceavailable basis.

Copy/correspondence shouldbesent toeditor.

Alladvertisingis payablein advance.

Allads are acceptedon a “good faith”basis.

Terms are“Until Forbid.”

Adsare Run of Press (ROP) unlessaccepted on

a premium contract basis.

Limited premium space/rates available.

To keep rates to a minimum, all advertising must be

prepaid according to the schedule below. In

exceptional cases where special artwork, or additional

production is required, the advertiser will be notified

and billed accordingly. Rates are not commissionable;

proofs are not supplied. SPMC does not endorse any

company, dealer or auction house.

Advertising Deadline: Subject to space availability,

copy must be received by the editor no later than the

first day of the month preceding the cover date of the

issue (i.e. Feb. 1 for the March/April issue). Camera

ready art or electronic ads in pdf format are required.

ADVERTISING RATES

Space 1 Time 3 Times 6 Times

Fullcolor covers $1500 $2600 $4900

B&W covers 500 1400 2500

Fullpagecolor 500 1500 3000

FullpageB&W 360 1000 1800

Halfpage B&W 180 500 900

Quarterpage B&W 90 250 450

EighthpageB&W 45 125 225

Required file submission format is composite PDF

v1.3 (Acrobat 4.0 compatible). If possible, submitted

files should conform to ISO 15930-1: 2001 PDF/X-1a

file format standard. Non-standard, application, or

native file formats are not acceptable. Page size:

must conform to specified publication trim size. Page

bleed: must extend minimum 1/8” beyond trim for

page head, foot, front. Safety margin: type and other

non-bleed content must clear trim by minimum 1/2”

Advertising copy shall be restricted to paper currency,

allied numismatic material, publications and related

accessories. The SPMC does not guarantee

advertisements, but accepts copy in good faith,

reserving the right to reject objectionable or

inappropriate materialoreditcopy.

The SPMC assumes no financial responsibility for

typographical errors in ads, but agrees to reprint that

portion of an ad in which a typographical error occurs

upon prompt notification.

Benny Bolin, Editor

Editor Email—smcbb@sbcglobal.net

Visit the SPMC website—www.SPMC.org

Rare Postal Note from Sitka Alaska Surfaces

Kent Halland & Charles Surasky .................................. 76

1862-1863 Legal Tender Classification Chart

Peter Huntoon & Doug Murray. .................................... 85

3rd Issue Fractional Currency Errors (Part 2)

Rick Melamed ............................................................... 92

Uncoupled—Joe Boling & Fred Schwan ................................. 106

Origin of the Train Vignette on T-39 Confederate Notes

Marvin Ashmore & Michael McNeil ............................. 116

John Benjamin Burton

Charles Derby ............................................................. 119

United Cigar Stores Company Coupons

Loren Gatch ................................................................ 129

1917 $1 Fr. 37a Error

Peter Huntoon ............................................................. 134

Small Notes—Two $5 Master Plate Proofs .......................... 136

Chump Change .................................................................... 139

Quartermaster Column ....................................................... 140

Obsolete Corner ................................................................... 142

President’s Message ........................................................... 144

New Members ....................................................................... 145

Editor Sez ............................................................................. 146

Membership Map ................................................................. 147

New SPMC Exhibit Program ............................................... 148

Money Mart .............................................................................. 151

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

73

Society of Paper Money Collectors

Officers and Appointees

ELECTED OFFICERS:

PRESIDENT--Shawn Hewitt, P.O. Box 580731,

Minneapolis, MN 55458-0731

VICE-PRESIDENT--Robert Vandevender II, P.O. Box 2233,

Palm City, FL 34991

SECRETARY--Jeff Brueggeman, 711 Signal Mtn., Rd. #197,

Chattanooga, TN 37405

TREASURER --Bob Moon, 104 Chipping Court,

Greenwood, SC 29649

BOARD OF GOVERNORS:

Mark Anderson, 115 Congress St., Brooklyn, NY 11201

Robert Calderman, Box 7055 Gainesville, GA 30504

Gary J. Dobbins, 10308 Vistadale Dr., Dallas, TX 75238

Pierre Fricke, Box 90538, Alamo Heights, TX 78209

Loren Gatch 2701 Walnut St., Norman, OK 73072

Joshua T. Herbstman, Box 351759, Palm Coast, FL 32135

Steve Jennings, 214 W. Main, Freeport, IL 61023

J. Fred Maples, 7517 Oyster Bay Way, Montgomery Village,

MD 20886

Michael B. Scacci, 216-10th Ave., Fort Dodge, IA 50501-2425

Wendell A. Wolka, P.O. Box 5439, Sun City Ctr., FL 33571

APPOINTEES:

PUBLISHER-EDITOR--Benny Bolin, 5510 Springhill Estates Dr.

Allen, TX 75002

EDITOR EMERITUS--Fred Reed, III

ADVERTISING MANAGER--Wendell A. Wolka, Box 5439

Sun City Center, FL 33571

LEGAL COUNSEL--Robert J. Galiette, 3 Teal Ln., Essex, CT 06426

LIBRARIAN--Jeff Brueggeman, 711 Signal Mountain Rd. # 197,

Chattanooga, TN 37405

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR--Frank Clark, P.O. Box 117060,

Carrollton, TX, 75011-7060

IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT--Pierre Fricke

WISMER BOOK PROJECT COORDINATOR--Pierre Fricke,

Box 1094, Sudbury, MA 01776

The Society of Paper Money Collectors was organized in 1961 and

incorporated in 1964 as a non-profit organization under

the laws of the District of Columbia. It is affiliated

with the ANA. The Annual Meeting of the SPMC i s

held in June at the

International Paper Money Show.

Information about the SPMC,

including the by-laws and

activities can be found at our website, www.spmc.org. .The SPMC

does not does not endorse any dealer, company or auction house.

MEMBERSHIP—REGULAR and LIFE. Applicants must be at

least 18 years of age and of good moral character. Members of the

ANA or other recognized numismatic societies are eligible for

membership. Other applicants should be sponsored by an SPMC

member or provide suitable references.

MEMBERSHIP—JUNIOR. Applicants for Junior membership must

be from 12 to 17 years of age and of good moral character. Their

application must be signed by a parent or guardian.

Junior membership numbers will be preceded by the letter “j” which

will be removed upon notification to the secretary that the member

has reached 18 years of age. Junior members are not eligible to hold

office or vote.

DUES—Annual dues are $39. Dues for members in Canada and

Mexico are $45. Dues for members in all other countries are $60.

Life membership—payable in installments within one year is $800

for U.S.; $900 for Canada and Mexico and $1000 for all other

countries. The Society no longer issues annual membership cards,

but paid up members may request one from the membership director

with an SASE.

Memberships for all members who joined the Society prior

to January 2010 are on a calendar year basis with renewals due each

December. Memberships for those who joined since January 2010

are on an annual basis beginning and ending the month joined. All

renewals are due before the expiration date which can be found on the

label of Paper Money. Renewals may be done via the Society website

www.spmc.org or by check/money order sent to the secretary.

Pierre Fricke—Buying and Selling!

1861‐1869 Large Type, Confederate and Obsolete Money!

P.O. Box 90538, Alamo Heights, TX 78209 ; pierrefricke@buyvintagemoney.com; www.buyvintagemoney.com

And many more CSA, Union and Obsolete Bank Notes for sale ranging from $10 to five figures

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

74

Contact JimG@Kagins.com or call 888.8Kagins to speak directly to Donald Kagin, Ph.D. who will arrange

to visit you and appraise your collecti on free and without obligati on.

To reserve your catalog for Kagin’s March 2019 National Money Show auction

contact us at : kagins.com, by phone: 888-852-4467 or e-mail: info@kagins.com.

Register to Bid and Reserve Your Catalog for Kagin’s

O cial Auction of the ANA National Money ShowTM

March 28-30, 2019

David L. Lawrence Convention Ctr, Pittsburgh, PA

National Bank Note Collection

The Joel Anderson Collection of the #1 Registry Set

of Treasury Notes of the War of 1812:

The First circulating U.S. Bank Note

Encased Postage Stamps

Additional consigned material includes:

– Colonial, U.S. coins and patterns

– Pioneer gold coins and patterns

– U.S. tokens and medals

– U.S. Colonial and Federal Currency

– Additional Asian, Mexican, German

and World paper currency

– Check out new Colonial and complete

Barber proof collection for sale now!

Mexican Bank Note Collection

The Carlson Chambliss

Collection:

Fractional Currency

Collection

New Zealand Currency

Collection Israeli Currency Collection

1869 $50 “rainbow” note

Currency Errors

Kagins-PM-NMS-Bid-Ad-02-13-19.indd 1 2/13/19 11:50 AM

An Extremely Rare Alaska Postal Note

Surfaces After 124 Years

by Kent Halland & Charles Surasky

When the words “Alaska” and “New

Discovery” are mentioned in a room full of currency

collectors, the room grows silent, ears perk up, and

all attention focuses on the person who spoke those

words. Why? In the numismatic specialty of paper

money collecting, 19th century notes from Alaska

are extremely rare and actively sought by collectors.

In the realm of Postal Note collecting, Alaska

notes are all but impossible to acquire. That is true

because there are just three known examples, all of

which reside in private hands, and none have

appeared in public for well over a decade. It is an

understatement to say we (the authors) were excited

to learn of the existence of a previously unreported

Postal Note from Alaska!

After an up-close inspection, we can now

confirm that an extremely rare and desirable U.S.

Postal Note, only the fourth Alaska note known to

21st century collectors, has surfaced. Figure 1 is a

cropped image of that note.

The note, bearing

serial number 854 and

catalogued as a “Rare

1894 Sitka, Alaska

Territory Postal Note in

superb condition” was

sold at auction in the

town of Brodheadsville

(pop. 1,800) in Monroe

County, Pennsylvania in

April, 2018. It was

purchased by an astute

currency dealer who

immediately sold it by

private treaty to a Postal

Note specialist for an

undisclosed price.

A Bit of Alaska History

Alaska wasn’t a State on September 3, 1883, the

day Postal Notes were first issued in the contiguous

States and Territories. It became our 49th State

nearly 76 years later – in early 1959. Here’s a brief

overview of Alaska’s and Sitka’s history:

Russia colonized what we know as southeastern

Alaska in the early 1700’s after fur traders returned

from the area with valuable sea otter pelts. This

region was known as Russian America from about

1808 until 1867.

The United States, under the direction of

Secretary of State William Seward, purchased

Alaska from Russia for $7.2 million (“in coin”

according to the handwritten receipt that now

accompanies the Treasury Warrant in the National

Archives). His critics derided the 1867 purchase,

calling it “Seward’s Folly,” but we now know his

decision proved fortuitous for our nation.

How Our Government Paid for Alaska

The Treasury Warrant shown below for $7.2

million was issued for the purchase of Alaska from

Russia. It is signed twice by Francis E. Spinner,

Treasurer of the United States from 1861 to 1875

-- during the terms of Presidents Lincoln, Johnson

and Grant. Spinner is credited with the creation of

U.S. Postal and Fractional Currency during the

Civil War – the immediate ancestors of Postal

Notes. The warrant was printed for the

government by the American Bank Note

Figure 1: A close-up showing Office of Issue and Serial

Number of this rare Postal Note.

Figure 2: The United States Treasury Warrant issued to pay Russia for Alaska.

Image Courtesy of the National Archives: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/301667

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

76

Company. Incidentally, ABNCo was awarded the

second four-year contract to engrave and print

Postal Notes in 1887.

Sitka, located on Alaska’s temperate southern

coast, some 850 miles north of Seattle, served as the

U.S. government capitol of the Department of

Alaska from its acquisition in 1867 to 1884.

Likewise, it was the seat of government for the

District of Alaska from 1884 to 1906, when Juneau

became the capitol.

Actually, there were two Russian settlements

formally known as Sitka. The first site was settled in

about 1799 and named Redoubt St. Archangel

Michael. This site is now in the Old Sitka State

Historical Park, located about seven miles north of

the city now known as Sitka.

Present-day Sitka’s first name, in Russian, was

Novo-Arkhangelsk. It was established in 1804 by

Alexander Baranov about two years after the Tlingit

destroyed the original settlement. Later re-named

New Archangel and finally Sitka, it served as the

capital of Russian America from 1808 until 1867.

Following the discovery of gold in 1883 and the

subsequent gold rush at the end of the 19th century,

Alaska’s population soared from roughly 33,400 to

63,500. Alaska was officially incorporated as a

Territory in 1912. It became the 49th State on

January 3, 1959.

Thus the region once referred to as Russian

America, and now known as Alaska, has been

officially recognized as a Department, a District, a

Territory, and a State since its purchase from Russia.

About U.S. Postal Notes

U.S. Postal Notes, a special kind of domestic

money order, were issued from September 3, 1883 to

June 30, 1894. The series was produced on two

Crane & Company watermarked banknote papers, by

three private firms, in a variety of designs. Official

government records indicate 70.8 million Postal

Notes were issued to the public. The vast majority

were issued, delivered, cashed, accounted for and

destroyed – as Congress had authorized. Of the

approximately 2,000 surviving examples, the most

frequently seen face values are one or two cents,

suggesting they were purchased and preserved as

collector’s items or souvenirs.

Government records show 3,046 Postal Notes

were issued by just four postal money order offices

in Alaska from late 1889 through June of 1894.

Given the dates of issue, those Postal Notes were

issued when the region was known as the District of

Alaska. To give an idea of rarity, the Postal Notes

issued in Alaska represent a mere 0.0043%

(3,046/70,824,173) of all Postal Notes issued in the

United States in the 19th century.

Sitka Postal Note #854

The immense rarity of Alaska Postal Notes has

prevented an in-person study of any examples by the

authors -- until now (fall of 2018). Before showing

images of the note in its entirety, we wish to discuss

our observations to explain why this is truly an

extraordinary Postal Note—one that has been

unknown to collectors for 124 years.

As we examined this note, our eyes were drawn

to several interesting aspects:

1. Unlike most surviving Postal Notes, Sitka #854

has a face value of five cents, suggesting it may

have been acquired to be used as Congress

intended: to purchase something, re-pay a debt

or transmit funds to a distant location.

Observe too, that the note is not signed by a

redeemer above the engraving company’s name;

Figure 3: Image of Sitka, Alaska circa 1890’s on a postcard.

Photo courtesy of the owner of the postcard.

Figure 4: Hand-written denomination of five cents.

Figure 5: Remitter’s signature is missing.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

77

the “star” below the fee shield is not punched

(Figure 6, below), and there is no paying office

date stamp on the reverse (Figure 7, also below)

– conclusive evidence that this note was never

cashed. These observations lead us to believe the

note was purchased as a souvenir, despite its

atypically high face value, or was set aside and

never used as intended.

Notice also, the dimes column (Figure 6)

was not punched in the “0” location. This

oversight was a common problem with Postal

Notes and one which allowed the nefarious

“raising” of the value of notes not punched

correctly.

Whatever this note’s intended purpose, it

was well cared for and is truly in superb

condition for a piece of paper “currency” that is

over 120 years old. How it found its way to rural

Pennsylvania is a mystery unlikely to be solved.

2. Sitka Postal Note #854 was produced by Dunlap

& Clarke, the Philadelphia-based printer that

won the final four-year Postal Note supply

contract (which commenced on August 15,

1891). The firm’s name appears at six o’clock on

the face of the note (Figure 8), making this a

Type V note.

Figure 8: Engraved name of printer.

Please continue reading. This will prove to be no

ordinary Type V note.

3. Of special interest is the postmaster signature on

the front of the note (Figure 9.) It reads “Paulina

Cohen.” She was the town’s postmistress from

August 22, 1890 until she resigned in 1900 -- to

manage the Baranof Hotel. She holds the

distinction of issuing the first Money Order at

the Sitka Post Office in 1892. In all likelihood,

she issued Sitka’s first Postal Note too.

Only a small percentage of the

approximately 2,000 surviving Postal Notes

exhibit the signature of a Postmistress, making

this a desirable example in that regard.

Miss Cohen was the daughter of Abraham

Cohen, one of Sitka’s best known residents,

likely because he had opened the Sitka Brewery

in 1868.

Following Miss Cohen’s postmistress

appointment, she moved the post office to a log

building on the corner of American and Lincoln

Streets in Sitka. She ensured the post office

operated regular hours on Wednesdays to sell

Figure 6: The Cancelling Star is not punched and the

dimes column is not punched.

Figure 7: Cancellation stamp

of paying office.

Figure 9: Signature of Postmistress Paulina Cohen

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

78

postage stamps and conduct the registry

business.

On April 4, 1892 her post office was

designated as a Money Order Office and Paulina

began selling Money Orders and Postal Notes

daily between 2 and 3 p.m., except Sundays

when the Post Office was closed. She later

expanded the operating hours of the office.

This Sitka Post Office, (Figure 11) may

have been the location where the Sitka #854

Postal Note originated, but that is pure

conjecture.

4. If you are not familiar with Alaska history,

please re-read the earlier paragraphs mentioning

Alaska’s official designations, then look

carefully at the wording in the issuing office’s

circular date stamp on the back of the note

(Figure 12.) For

a reason that

defies fact, it

identifies Alaska

as a “Territory”

(abbreviated

“TER.”). We

know Alaska

was a U.S.

District when

this note was

issued, so the

postmaster’s

date stamp is

factually wrong. That makes it extra-interesting

and worthy of further investigation. Why was the

term “Territory” used rather than “District”?

5. The issue date (see Figures 1 and 12) of Sitka

Postal Note #854 is January 27, 1894 (a

Saturday), making this the earliest issue date

known for any surviving Postal Note from

Alaska.

6. Now for something special for all Postal Note

enthusiasts.

Postal Note experts have recognized a

“new” variety of the Type V notes since it was

first reported by Robert Laub in 2010.

Look at the three images on the next page.

Figure 13 is from a Type IV reverse engraved

and printed by the American Bank Note

Company (ABNCo) during the second Postal

Note contract (1887-1891.)

Figure 14 is the standard Type V reverse,

believed to have been created from ABNCo

plates modified by Dunlap & Clarke (D&C) by

removing the words “American Bank Note

Company, New York”, but leaving the

scrollwork intact.

Notes issued as early as January 1894 began

appearing with a new variety of reverse--one in

which the residual scrollwork had been

completely removed. The authors have

designated this new reverse as a Type V.01. The

Sitka #854 Postal Note, part of which is shown

in Figure 15, is missing the scrollwork and

therefore designated as the Type V.01 reverse

variety. (The Postal Note identification system

in use since the 1970s will be updated and

expanded in our upcoming book.)

Figure 10: Photograph by Reuben Albertstone showing

Paulina Cohen (standing) and her sister Augusta Cohen,

ages 25 and 16 respectively. Image PH271 coutesy of the

Sitka Historical Society & Museum.

Figure 11: Post Office at Sitka. Photo courtesy of the

Alaska State Library, Frank LaRoche Photographs

Collection, ASL-P130-031.

Figure 12: Issuing Office Date

Stamp

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

79

Figure 13: Type IV Reverse

(has scrollwork and company information.)

Figure 14: Type V Reverse

(has scrollwork, but no company

information.)

Figure 15: Type V.01 Reverse

(has NO scrollwork or company

information.)

7. Here are the full images of this Postal Note.

Figure 16: Obverse of Sitka,

Alaska Postal Note #854, issued

January 27, 1894.

Image courtesy of the owner.

Figure 17: Reverse of Sitka,

Alaska Postal Note #854, issued

January 27, 1894.

Image courtesy of the owner.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

80

Alaska Postal Notes in Collectors’ Hands

With the appearance of Sitka #854, a total of

four Postal Notes from Alaska have been identified

by modern collectors and researchers. Astoundingly,

not one example is from either of modern Alaska’s

two most populous cities: Anchorage and Fairbanks.

This is because neither of those cities existed during

the 1883-1894 Postal Note era.

The surviving notes are from three of the four

Alaska Post Offices designated as Money Order

Offices qualified to issue Postal Notes from late 1889

to June 30, 1894. The previously reported Alaska

Postal Notes were all identified as being the Type V

design in the late Jim Noll’s 2004 census entitled

“Index of U.S. Postal Notes in Collectors Hands”.

Because Noll did not list the new variety in his

census, it is possible that any one, two or all three

could be the Type V.01 variety.

As of this writing, the known Alaska notes are

as follows:

1. Douglas, AK # 819, issued May 18, 1894 in

the amount of two cents.

2. Kodiak, AK # 67, issued June 11, 1894 in

the amount of two cents.

3. Sitka, AK # 854, issued January 27, 1894

in the amount of five cents.

4. Sitka, AK # 1051, issued June 18, 1894 in

the amount of two cents

Also noticeably absent from the list of

surviving Alaska Postal Notes: an example from

Juneau. Yes, the town destined to become the

Capital of Alaska has no surviving Postal Notes

reported.

It is important to pause here and to make an

important fact known to all readers: government

records frequently conflict. Regarding Alaska, one

source says two Money Order Offices were in

operation in October of 1889 while another source

does not list any Money Order Offices until 1890.

Until this conflict is resolved, we have chosen to list

the following months we believe each the four

Alaska post offices were designated “Money Order

Offices:” Douglas in October of 1889, Juneau in

October of 1889, Sitka in April of 1892 and Kodiak

in July of 1893.

Based on their earliest possible dates of

operation, we know the four offices did not issue any

Postal Notes between 1883 and 1888, so there were

zero Alaska Postal Notes issued on any of Homer

Lee Bank Note Company’s designs. Repeat, zero.

It’s not even a remote possibility. We are sure some

collectors will be saddened by this revelation

because it decreases the number of Postal Note types

available from Alaska.

We also know Dunlap & Clarke did not begin

producing the Type V design until their contract

commenced on August 15, 1891. Thus, there is the

possibility that one or both of the American Bank

Note Company (ABNCo) Type IV (with engraved

date 188__) or Type IV-A (with engraved date

189__) designs were issued in Alaska by two of the

authorized offices that began operation in 1889.

So, until researchers can confirm the date that

each of the Alaska Post Offices was designated as a

Money Order Office and was supplied with Postal

Notes for issuance, we cannot be sure if any of those

offices first issued Postal Notes in 1889 or 1890.

Further research will determine if one, or both

ABNCo designs were issued in Alaska. None have

been reported to date.

Those ABNCo notes, if any exist, will be

extremely scarce because only two offices could

have issued the ABNCo design. Those offices were

Douglas and Juneau, Alaska.

With none reported, can we determine how

many Postal Notes the Juneau office could have

issued?

The serial numbers of the known notes indicate

the minimum quantity of Postal Notes issued by

three of the four Alaska offices. We can draw on this

information to determine the quantity likely issued

by the Juneau post office.

The government data (see Table 1) shows there

were only 3,046 Postal Notes with face

values totaling $5,768.68 issued throughout the

entire expanse of the District of Alaska by the four

issuing post offices.

By adding the highest known serial numbers of

reported notes (using the highest serial, #1051 from

Sitka), we know there were at least 819 + 67 +1051

Table 1

Alaska Postal Notes Issued

Fiscal Year

Ending on

June 30 of

Quantity

Issued

Total Value

Issued

Average

Note

1890 158 $ 270.48 $ 1.71

1891 376 $ 720.94 $ 1.92

1892 453 $ 836.77 $ 1.85

1893 906 $ 1,796.47 $ 1.98

1894 1,153 $ 2,144.02 $ 1.86

TOTAL 3,046 $ 5,768.68 $ 1.89

This Alaska Postal Note issuance data was obtained from the

Annual Reports of the Postmaster-General of the United States

for fiscal years ending June 30, 1890, 1891, 1892, 1893, and 1894.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

81

= 1,937 Postal Notes issued by those three offices,

leaving a maximum of 1,109 notes that could have

been issued in Juneau. This quantity is probably too

high because we have not accounted for quantities

issued by the other three offices between the date of

their reported notes and June 30, 1894—the last day

of issue for all Postal Notes.

In all likelihood, the Juneau Money Order

Office issued fewer than 1,100 notes, perhaps far

fewer. Why? We know the booklets originally

containing the other three offices’ notes were likely

delivered to each office in increments of 100 notes.

Rounding up each of the previously mentioned

quantities to the next multiple of 100 results in 900 +

100 + 1,100 = 2,100 notes that were sent to the other

three offices in bound booklets.

Assuming the other three offices issued every

note in their respective booklets by June 30, 1894,

we can calculate the minimum number of postal

notes that Juneau could have issued by subtracting

2,100 from 3,046 to arrive at 946 as the likely

minimum number of notes Juneau issued. Given the

number of Postal Notes issued in the other authorized

offices throughout the District, we can estimate with

some confidence that the Juneau office issued

between 946 and 1,109 Postal Notes.

If a note from Sitka can surface after 124 years,

then perhaps one day soon collectors will rejoice

when a new discovery note from Juneau surfaces.

So start searching! The lucky finder will hold a

very collectable Juneau, Alaska Postal Note worth

thousands of dollars. Perhaps it will even be an

elusive ABNCo issue!

If you find one, please don’t keep it a secret! Let

us know of your discovery!

About the Authors:

Kent Halland has been researching United

States Postal Notes and Money Orders for nearly a

decade with an emphasis on United States Post

Offices, Stations, and Sub-stations that issued those

monetary instruments in the 19th century. Kent is a

life member of the SPMC.

Charles Surasky has collected and written about

U.S. Postal Notes for five decades. He has had more

than one million words published.

The authors are finishing a Postal Notes book

that will include previously unknown facts and data

(such as the August 15, 1891 contract date

mentioned in the article), plus the latest census of all

known notes. If you would like to receive a first

edition, send your name and email address to:

proeds@sbcglobal.net.

References and Additional Reading

“A Forgotten Chapter: The United States Postal Note”, Nick

Bruyer, Paper Money, Whole Number 48-51.

“A 131-Year Old Mystery Solved,” Kent Halland and Charles

Surasky, Paper Money, November/December 2016.

The Comprehensive Catalog of U.S. Paper Money, Fifth

Edition, Gene Hessler, pages 387-389.

“The U.S. Postal Notes of 1883-1894: The Three Key Pieces

of Federal Legislation”, compiled and edited by

Charles Surasky, 2011. (Includes a lengthy list of

reference sources).

“Index of U.S. Postal Notes in Collectors Hands” compiled in

2004 by James E. Noll.

States Admitted to the Union: 1883 to 1959

State Date

Number State Admitted

39 North Dakota November 2, 1889

40 South Dakota November 2, 1889

41 Montana November 8, 1889

42 Washington November 11, 1889

43 Idaho July 3, 1890

44 Wyoming July 10, 1890

45 Utah January 4, 1896

46 Oklahoma November 16, 1907

47 New Mexico January 6, 1912

48 Arizona February 14, 1912

49 Alaska January 3, 1959

50 Hawaii August 21, 1959

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

82

PMGnotes.com | 877-PMG-5570 United States | Switzerland | Germany | Hong Kong | China | South Korea | Singapore | Taiwan | Japan

THE CHOICE IS CLEAR

Introducing the New PMG Holder

PMG’s new holder provides museum-quality display, crystal-clear optics

and long-term preservation. Enhance the eye appeal of your notes

with the superior clarity of the PMG holder, and enjoy peace of mind

knowing that your priceless rarities have the best protection.

Learn more at PMGnotes.com

16-CCGPA-2889_PMG_Ad_NewHolder_PaperMoney_JulyAug2016.indd 1 5/27/16 8:12 AM

Lyn Knight Currency Auct ions

If you are buying notes...

You’ll find a spectacular selection of rare and unusual currency offered for

sale in each and every auction presented by Lyn Knight Currency

Auctions. Our auctions are conducted throughout the year on a quarterly

basis and each auction is supported by a beautiful “grand format” catalog,

featuring lavish descriptions and high quality photography of the lots.

Annual Catalog Subscription (4 catalogs) $50

Call today to order your subscription!

800-243-5211

If you are selling notes...

Lyn Knight Currency Auctions has handled virtually every great United

States currency rarity. We can sell all of your notes! Colonial Currency...

Obsolete Currency... Fractional Currency... Encased Postage... Confederate

Currency... United States Large and Small Size Currency... National Bank

Notes... Error Notes... Military Payment Certificates (MPC)... as well as

Canadian Bank Notes and scarce Foreign Bank Notes. We offer:

Great Commission Rates

Cash Advances

Expert Cataloging

Beautiful Catalogs

Call or send your notes today!

If your collection warrants, we will be happy to travel to your

location and review your notes.

800-243-5211

Mail notes to:

Lyn Knight Currency Auctions

P.O. Box 7364, Overland Park, KS 66207-0364

We strongly recommend that you send your material via USPS Registered Mail insured for its

full value. Prior to mailing material, please make a complete listing, including photocopies of

the note(s), for your records. We will acknowledge receipt of your material upon its arrival.

If you have a question about currency, call Lyn Knight.

He looks forward to assisting you.

800-243-5211 - 913-338-3779 - Fax 913-338-4754

Email: lyn@lynknight.com - support@lynknight.c om

Whether you’re buying or selling, visit our website: www.lynknight.com

Fr. 379a $1,000 1890 T.N.

Grand Watermelon

Sold for

$1,092,500

Fr. 183c $500 1863 L.T.

Sold for

$621,000

Fr. 328 $50 1880 S.C.

Sold for

$287,500

Lyn Knight

Currency Auctions

Deal with the

Leading Auction

Company in United

States Currency

1862-1863 Legal Tender

Classification Chart

Purpose

Our purpose is to provide a comprehensive and straight forward classification guide that will allow

you to unambiguously assign a Friedberg catalog number to 1862 and 1863 legal tender notes. We are using

Friedberg catalog numbers because this is the most widely used system of numbers within our hobby. Once

you assign the right number to your note, we all will be talking the same language with respect to it.

No United States type notes have caused more confusion than the 1862-1863 legal tender issues.

The problem is that there are so many arcane variables on these notes that it is easy to misclassify them.

Consequently, they are the most erroneously attributed notes in auction catalogs, grading company holders

and censes.

The process is to match all the diagnostics on your note with the appropriate entry in the

accompanying table. Then read the Friedberg number from either the first or last column.

Notice that the Friedberg numbers are out of order for the various denominations. We have

attempted to put the entries into the approximate chronological order in which they were made. We say

approximate because more than one variety was being printed at the same time during some periods. Also,

some varieties reappeared after not having been used for a while.

The Friedberg numbering system is imperfect, but that is not our problem. Very little was known

about these notes when Friedberg first assigned numbers to them. The way his numbering system was set

up, all he could do was assign a number to each of the known varieties by series and denomination in the

order in which he thought they were produced. He then moved on to the next series and continued

numbering. As new varieties were discovered, he had no option but to sandwich the new entries into his

listing by assigning suffix letters to them in succeeding editions. However, the letters were assigned in the

order in which the discoveries were made, which had nothing to do with the order in which the varieties

were produced.

Some of the varieties that have been assigned Friedberg numbers are not varieties at all, but

misprints. The best example is $2 1862 Fr.41d where the Treasury seal was inverted for at least one printing.

This is a misprinted Fr.41c. Another is $20 1863 Fr.126c where the left serial number was misplaced for

an entire printing making the notes different from Fr.126b. Doug found a letter in his research where the

printer was requested to be careful not to make that mistake again. It certainly created a variety and they

made plenty of them so call it what you like, a legitimate variety or a misprint!

Of course, this type of numbering system leads to chaos, and that is exactly what happened. That

chaos contributes to the difficulty people have when they attempt to classify these notes. At this point, we

simply have to acknowledge that the Friedberg numbers are an arbitrary means to allow us to communicate.

End of story, for better or worse.

Doug Murray, who seriously researched these notes for decades, unraveled the chronology of these

issues and determined the actual or approximate numbers of each variety that were printed. He even

deduced that certain listed varieties never were printed. Examples being Fr. 149 and 166, respectively a $50

and $100.

We have provided census data only for the flaming rarities; that is, the varieties for which fewer

than 10 are reported.

There is a possibility that you may discover an unreported variety. If you think you have one, send

a 300-dpi color scan of it to peterhuntoon@outlook.com. If indeed it is new, you will win for yourself a

new listing and the resulting publicity that goes with such a discovery. These wonderful notes were the first

true circulating U. S. Treasury issues so there is a great deal of interest in them and they have high visibility.

The Paper

Column

Peter Huntoon

Doug Murray

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

85

Classification guide for assigning Friedberg numbers to 1862 and 1863 Legal Tender Notes.

Series No.

Fr. No. Act Plate Date Series Number Placement Imprints Monogram Seal Serial Numbers

$1 1862

17 Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 1 left National-American none 1st seal on left serial

17d Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 1 left National-American ABC 1st seal on left serial

17b Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 1 left National-American ABC 2nd seal on left serial

17a Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 1-166 left National-American ABC 2nd left serial on green counter

16b Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 166-174 left National-National none 2nd left serial on green counter

16 1st group Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 174-234 left National-National none 2nd left serial on green counter

17c Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 199-204 left National-American ABC 2nd left serial on green counter

16a Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 204-219 left National-National ABC 2nd left serial on green counter

16 2nd group Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 219-234 left National-National none 2nd left serial on green counter

16c Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 235-284 right National-National none 2nd left serial on green counter

$2 1862

41b Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 1 right American-National none 1st no face plate number left of portrait

41c Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 1-2 right American-National none 2nd no face plate number left of portrait

41d Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 1 right American-National none 2nd inverted no face plate number left of portrait

41a Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 3-88 right American-National none 2nd face plate number left of portrait

41 Jul 11, 1862 Aug 1, 1862 88-171 right National-National none 2nd face plate number left of portrait

$5 1862/1863

61 Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 no series none American none 1st one serial number

61a Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 2-59 upper left American none 1st one serial number

61b Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 59-70 upper left American none 2nd one serial number

61c Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 71-119 lower left American none 2nd one serial number

62 Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 New 1-23 lower right American-National none 2nd one serial number

63 Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 24-65 lower right American-National none 2nd one serial number

63a Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 65-75 lower right American-American none 2nd one serial number

63b Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 75-83 lower right American-American none 2nd two serial numbers

$10 1862/1863

93a Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 1 upper right American-Ptd by Nat none 1st upper right corner one serial number

93a-I Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 1 upper right American-Ptd by Nat none 1st upper right corner one serial number

93b Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 1-9 upper right American-Ptd by Nat none 1st right center one serial number

93c Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 1-25 upper right American-Ptd by Nat none 1st right center one serial number

93e Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 5-7 census upper right American-Ptd by Nat none 1st right center one serial number

93f Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 5 census upper right American-Ptd by Nat none 1st right center one serial number

93d Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 26-27 upper right American-Ptd by Nat none 1st right center one serial number

93 Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 28-63 upper right American-Ptd by Nat none 2nd right center one serial number

94 Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 New 1-15 upper right American-National none 2nd right center one serial number

95 Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 16-40 upper right American-National none 2nd right center one serial number

95c Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 40-44 upper right American-National none 2nd right center one serial number

95a Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 44-48 upper right American-American none 2nd right center one serial number

95b Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 48-56 upper right American-American N 2nd right center two serial numbers

$20 1862/1863 one serial number

124a Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 no series none American none 1st one serial number

124b Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 2-12 top center American none 1st one serial number

124 Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 12-24 top center American none 2nd one serial number

125 Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 New 1-8 top center National-American none 2nd one serial number

126 Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 9-18 top center National-American none 2nd one serial number

126a Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 18-20 top center American none 2nd one serial number

126c Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 20-21 top center American none 2nd two serial numbers in line with each other

126b Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 21-28 top center American none 2nd two serial numbers, left in lower left corner

$50 1862/1863

148 Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 1-3 upper right National none 1st one serial number

148a Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 3-5 upper right National none 2nd one serial number

150 Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 1 upper right National none 2nd one serial number

150b Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 1-2 upper right National-American none 2nd one serial number

150a Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 2 upper right National-American none 2nd one serial number

$100 1862/1863

165 Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 no series none National ABC 1st one serial number

165b Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 2 lower right National none 1st one serial number

165a Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 2-3 lower right National none 2nd one serial number

167b Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 1 lower right National none 2nd one serial number

167 Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 1 lower right National-American none 2nd one serial number

167a Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 1-2 lower right National none 2nd two serial numbers

$500 1862/1863

183 Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 no series none American none 1st one serial number

183a Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 no series none American none 2nd one serial number

183b Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 New 1 left American-National none 2nd one serial number

183e Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1862 New 1 left American-National none 2nd one serial number

183c Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1862 New 1 left American none 2nd one serial number

183f Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 1 left American none 2nd one serial number

183d Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 1 left American none 2nd two serials with left in brackets with different font

$1000 1862/1863

186 Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 no series none American none 1st one serial number

186a Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 no series none American none 2nd one serial number

186b Feb 25, 1862 Mar 10, 1862 New no series lower left American-National none 2nd one serial number

186c Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1862 New no series lower left American-National none 2nd one serial number

186e-1 Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1862 New no series lower left American none 2nd one serial number

186d Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New no series & 2 lower left American none 2nd one serial number

186e Mar 3, 1863 Mar 10, 1863 New 2 lower left American none 2nd two serials with left in brackets with different font

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

86

Green Underprinted Number

Patent Date Back Number Printed Special Characteristic Reported Fr. No.

$1 1862

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 5,000 est 4 17

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 7,000 est 6 17d

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 12,000 est 1 17b

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 16,512,000 est plates 1 to 45 17a

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 810,000 plates 1-16, 18, 21, 23, 25-45 16b

none 2nd obligation 5,854,000 plates 1-16, 18, 21, 23, 25-45 16 - 1st group

none 2nd obligation 50,000 est with Fr.16 plates 17, 19, 20, 22, 24 17c

none 2nd obligation 150,000 est with Fr.16 plates 17, 19, 20, 22, 24 16a

none 2nd obligation 5,854,000 plates 17, 19, 20, 22, 24 16 - 2nd group

none 2nd obligation 4,946,000 16c

$2 1862

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 10,000 est error - plate number omitted 6 41b

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 178,000 est error - plate number omitted 6 41c

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 12,000 est error - seal inverted & no plate no. 3 41d

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 8,511,160 est 41a

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 8,318,840 41

$5 1862/1863

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 100,000 61

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 5,750,000 est 61a

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 1,150,000 est 61b

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 4,900,000 61c

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 2,300,000 62

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 4,132,764 63

none 2nd obligation 1,000,000 63a

none 2nd obligation 867,236 63b

$10 1862/1863

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 60,000 est no starburst bottom 5 93a

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 20,000 est with Fr.93a starburst bottom 2 93a-I

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 120,000 est with Fr.93c no starburst bottom 93b

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 2,220,000 est starburst bottom 93c

none (error) 1st obligation 60,000 est with Fr.93b no starburst bottom 5 93e

none (error) 1st obligation 20,000 est with Fr.93c starburst bottom 3 93f

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 200,000 est starburst bottom 7 93d

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 3,600,000 est starburst bottom 93

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 1,500,000 starburst bottom 94

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 2,430,504 starburst bottom 95

April 28, 1863 2nd obligation 370,000 starburst bottom 95c

April 28, 1863 2nd obligation 400,000 starburst bottom 95a

April 28, 1863 2nd obligation 800,496 starburst bottom 95b

$20 1862/1863

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 100,000 2 124a

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 1,050,000 est 124b

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 1,250,000 est 124

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 800,000 125

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 920,984 126

none 2nd obligation 225,000 126a

none 2nd obligation 66,016 est error - left serial number was misplaced 9 126c

none 2nd obligation 734,000 est 126b

$50 1862/1863

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 260,000 est 148

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 173,600 est 6 148a

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 32,000 150

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 70,504 1 150b

April 28, 1863 2nd obligation 65,000 150a

$100 1862/1863

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 100,000 1 165

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 35,000 est 2 165b

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 155,000 est 6 165a

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 24,000 2 167b

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 29,440 2 167

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 56,560 167a

$500 1862/1863

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 26,000 1 183

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 12,000 possibly printed 183a

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 5,000 possibly printed 183b

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 22,828 error - plate date should be Mar 10, 1863 183e

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 22,000 error - plate date should be Mar 10, 1863 3 183c

none 2nd obligation 8,000 1 183f

none 2nd obligation 20,000 1 183d

$1000 1862/1863

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 12,000 186

30 JUNE 1857 1st obligation 10,000 possibly printed 186a

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 2,500 possibly printed 186b

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 24,904 error - plate date should be Mar 10, 1863 1 186c

30 JUNE 1857 2nd obligation 22,000 error - plate date should be Mar 10, 1863 186e-1

none 2nd obligation 64,000 2 186d

none 2nd obligation 20,000 1 186e

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

87

Obligations – backs

Several key elements – faces

Series Numbers

The serial numbering system used on these notes is coupled with the series. Each denomination

began with Series 1. The numbering heads used by the bank note companies had five number wheels so the

highest number they could print was 99999. However, they hand set 100000 to round out a series. They

then advanced the series and printed the next 100000 and so on.

In order to change the series, which was a number etched into the surface of the face plates, they

had to burnish off the old number and etch in the next.

In some cases, they did not etch in a 1 for the first 100,000 notes. See $5 Fr.61, $20 124a, $100

165, $500 183, 183a, $1000 186, 186a. The series number was omitted by mistake on some $2 Fr.41b, 41c,

41d notes.

Figure 1. First obligations on left, second on right. The distinction is that the first provides for the exchange of

the notes for U. S. bonds.

Figure 2. This is a Fr.95 note with March 3, 1863 act date, American & National bank note

company imprints, March 10, 1863 plate date, series = 18 New Series, and 30 JUNE 1857 patent

date.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

88

Bank Note Company Imprints

The contracts for engraving the master dies for the various denominations were spread among the

American and National bank note companies as follows: National $1, $2, $50, $100, American $5, $10,

$20, $500, $1000, so their respective imprints were placed on the dies.

However, a second imprint occurs on most notes, some being duplicates, others being the other

company. We have not found an official explanation for the second imprint or discerned a pattern that

explains every instance. We simply don’t understand how the imprint system worked.

Patent Dates

The green ink used to print the green tints on the faces of the notes were patented anti-counterfeiting

inks. The patent holders claimed the green couldn’t be removed without damaging the black intaglio

printing and the paper, which would prevent counterfeiters from obtaining a sharp photographic image of

the black overlay. The Treasury paid a royalty for the use of the inks, first for the Matthews and next for

the Eaton formulas; however, neither worked. The patented inks were then dropped from use.

The patent dates were incorporated into the designs of the intaglio plates used to print the green

tints. Their locations varied depending on denomination, but they are found free-standing under some part

of the tint. They can be difficult to see on well-circulated specimens. The Eaton ink is decidedly bluish.

The June 30, 1857 date was omitted from one or more of the tint plates used to print $10 1862

Series 5 through 7 notes, thus creating the Fr. 93e & f varieties, which technically classify as errors.

Figure 4. George Matthews’ June 30, 1857 and Asahel K. Eaton’s April 28, 1863 patent dates on 1862 and 1863

Legal Tender Notes were for anti-photographic green tint inks.

Figure 3. Someone put together this neat

pair, not a rollover pair because the 100000

is series 73 and the 1 is series 20. The 100000

had to be hand set because the numbering

heads had only 5 number wheels. Lyn Knight

Auction photo.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

89

Monograms

Corporate monograms were added to a few of the face plates, probably to reveal who printed them.

See ABC for $5 Fr.16a, 17a, 17b, 17c, 17d, $100 Fr.165 and N for $10 Fr.95c.

Seals

Starburst on some $10s

The first six $10 plates were altered Demand Note plates. They have no starburst in the center of

the lower border. Successive plates made exclusively for the legal tender issues incorporate the starburst.

This detail applies only to the $10 notes and is listed in the column labeled “Special Characteristics.”

Figure 5. Bank note company

monograms: ABC on Fr.17a

(left) and N on Fr.95b (right).

Figure 6. The background behind the shield is solid on the first seal (left).

Figure 7. The bottom border of the $10s come without (top) and with (bottom) a starburst in the center.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

90

3rd Issue Fractional Error Notes (25¢ to 50¢) – Part 2

By Rick Melamed

In previous issues of Paper Money, we explored 2nd issue fractional surcharge errors and fractional error notes

from the 3rd issue between the 3¢ to 25¢ denominations. In this issue we complete the 3rd issue research with a

presentation of the 25¢ (Fessenden) and the 50¢ (Justice and Spinner) error fractionals.1 Unlike small sized U.S.

currency, which has been robustly researched and catalogued, research on fractional error notes is a somewhat under-

represented. Therefore, a broad overview dedicated to just fractional errors should be well received. Drawing from

an array of high-quality images not available 15 years ago, we are able to deliver a more detailed overview on this

subject.

A great debt of gratitude must be extended to the father of fractional research, Milton Friedberg. His reference

book ‘Encyclopedia of Postage and Fractional Currency’ contains extensive research on all things fractional, with a

portion devoted to errors. However, while inverted printing errors were included, other types of errors (i.e. offsets,

misalignments, gutter folds, etc.) were not. Also, the images in Milt’s reference were in black and white and were

not of optimal quality.

Thanks must also be extended to former FCCB (Fractional) President, Tom O’Mara, and SPMC and FCCB

former President and current editor, Benny Bolin, for their charts of 3rd issue fractional errors. They’ve allowed me

to reprint their original charts and combine them with a host of scans to give us an updated article. Benny shared

some of his interesting errors from his personal collection. The images from Tom’s vast error collection (auctioned

in 2005 by Heritage), as well as John Ford’s large collection of error fractionals (auctioned by Stack’s from 2004-

2007), were also a huge help.

3rd issue fractionals offer a type of error found nowhere else in U.S. issued currency; the use of bronze

surcharges. These bronze surcharges were one of the many anti-counterfeiting measures undertaken by the U.S.

Treasury. The process was fairly straightforward; first glue was applied to the notes, then a bronzing powder was

added. The bronzing that adhered to the note resulted in the familiar surcharges. The improper application of glue,

as well as the multitude of inverted possibilities, produced a fascinating array of bronzing errors. This array of

bronzing errors, combined with the more recognizable traditional currency errors, results in an extensive variety of

error notes.

A. 3rd Issue 25¢ Fessenden Errors. Fessenden fractionals are an underappreciated series. While

Spinner and Justice fractionals get more attention from collectors, the Fessenden is a rich series with many

varieties and sub-varieties. The mystique of the Fr. 1299 and Fr. 1300 with its thick coarse paper, solid front

surcharges and elusive ‘M-2-6-5’ reverse corner surcharges are very desirable, and my personal favorite. It

demonstrates how far the Treasury went to thwart the counterfeiters. Too far in actuality, since they were

rather difficult to produce. This made them a short-lived series, but a nice well-preserved example is

something to be treasured.

As it relates to errors; with all those varieties, there a quite a few possibilities.

1. Inverted Reverse Engraving and Surcharge Errors. The chart shown contains the general

Friedberg numbers (in the far-left column); individual Milton alpha-numeric designations

(i.e.: 3R25.2j) are included where applicable. There are three categories for this kind of error.

a. Inverted Back Engraving – Just the back design is inverted; the face engraving and all the surcharges

are normal.

b. Inverted Back Surcharges – The design and front surcharge are normal; the back surcharge is inverted.

c. Total Back Inverted – The face surcharge and design are normal; the back surcharge and design are

inverted.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

92

3rd issue - 25 Cents

Friedberg No.

Inverted Back

Engraving

Inverted Back

Surcharges

Total Back

Inverted

1291 Unknown 3R25.1h - Unique Unknown

1292 Unknown Unknown Unknown

1294 3R25.2j - Reported 3R25.2i - 12 Known 3R25.2h - Reported

1295 3R25.2k - unique 3R35.2v - unique 3R25.2o - Unique

1296 Unknown Unknown Unknown

1297 Unknown 3R25.4f - unique Unknown

1298 3R25.4b - 2-3 Known 3R25.4e - Unique Unknown

1299 Unknown 3R25.3f - Unique - Ford Unknown

1300 Unknown Unknown Unknown

Red back Fessenden surcharge errors are unique; only one example is known to exist. The rarity of this note

cannot be understated. Considering the multitudes of green back inverts that exist, only one solitary red back inverted

Fessenden is known. Aside from the Fr. 1357 with the inverted reverse (~10 known) there are no known red back

inverts for the Spinner, 10¢ Washington and 5¢ Clark. This is also true for inverted plate number notes (see below).

There are dozens of examples of inverted/mirrored plate numbers on green backs but only one red back example with

an invert (an Fr. 1251 wide margin specimen reverse with an inverted #11). This begs the question: why was extra

care used on the red backs?

The next string of Fessenden’s show all three types of surcharge errors: inverted back engraving,

inverted back surcharge and total inverted back.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

93

Fiber paper Fessenden errors are rare and quite desirable. About five invert errors are known for

all 25¢ fiber varieties. Note the inverted ‘25’ and inverted the ‘M-2-6-5’ reverse corner surcharge.

2. Fr. 1296 Engraving Error. A total of 146 plates were used to engrave the Fessenden note:

55 plates for the back design and 91 plates for the face. 90 of the 91 plates were engraved correctly; a

single plate (Pate #144) was engraved incorrectly. On the left side of the 12-note sheet plate, a small

‘a’ was engraved as a sheet locator. The normal Fr. 1295 had the ‘a’ designator positioned to the left of

Colby’s signature. On the FR. 1296, the engraver placed the ‘a’ 7mm to the right creating a very

desirable engraving error. How valuable? A gem Fr. 1296 can easily be worth 15-20 times more than

an Fr. 1295.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

94

Fr. 1294-SP-WM with 90° rotated plate #13. A full sheet of Fessenden wide margin specimens

consists of eight notes: five horizontal (normal) and three rotated 90°, such that the Fessenden’s are laid out

vertically with the portrait looking straight up. The sheet plate #13 was engraved normally, but when the

sheet was cut into individual notes, the plate number would appear to be rotated. Not an error, but it sure

looks like one.

3. Shifted face surcharge. The bronze surcharges on the Fessenden face are shifted quite

significantly to the left.

4. Inverted ‘M’ Surcharge. On all fiber Fessenden’s there is an ‘M-2-6-5’ surcharge stamped

onto the back corners. In this rare example of an Fr. 1297 (possibly unique), the ‘M’ in the upper left

corner was engraved upside down so the surcharge looks like a ‘W.’

5. Extra Bronzing. Only 2nd and 3rd issue fractionals contain bronze surcharges. On this

example, extra bronzing had been applied to the note. The Fr. 1298 Fessenden is a dramatic example

with an extraneous rectangular bronze patch on the left side of the note.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

95

6. Butterfly Error. A butterfly error is a fold along the corner of a note which, after the cutting

process, results in an excess flag of paper. It roughly resembles a butterfly's wing.

The first Fessenden displays a butterfly error

on the bottom left.

This Fessenden face has a butterfly on the

bottom right.

7. Fessenden Fold-Over Error. The upper left corner on this Fr. 1299 solid surcharge

Fessenden was folded during the printing of the back, resulting in part of the reverse design on the fold.

8. Gutter Fold Error. Gutter folds are the result of the uncut sheets being sent through the

press with a wrinkle or wrinkles in the paper. When pulled, the gutter reveals a gap in the note design.

While they are relatively common in small sized currency, in fractionals they are rare.

The Fr-1294-SP-WM shown below (front and back) has discernable gutter fold.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

96

9. Extra Reverse Surcharges. This pair of fiber paper Fessenden’s each have additional

surcharges on the back. The first has the ‘25’ shifted so low that there is an extra set of ‘6’ & ‘5’ on the

note; the second note has an extra and partial ‘2’ & ‘6’ on the very left margin.

11. Inverted Bronze ‘SPECIMEN’ Imprint on the Back of a Fessenden Specimen. The back of

every Fessenden Specimen has the bronze imprint inverted. So finding the imprint right-side up would

be the rarity.

A. 50¢ Denomination – Spinner and Justice Errors. The undisputed kings of fractionals are the 50¢

Justice and Spinner notes. They contain the most varieties, fetch the highest average price per note at

auctions, and offer a large amount of error varieties.

1. Inverted Reverse Engraving and Surcharge Errors. With the all the varieties of Justice and

Spinner notes, it would be impractical to show every type of inverted surcharge error per Friedberg number.

So we endeavor to show one example of each inverted variety: Type 1 back with and without the corner

surcharges and Type 2 reverses. Since the Type 1 reverses were the same for Justice and Spinner notes, the

actual amount to showcase is less than one might think. We color coded the entries tying the charts to the

images.

Citing former FCCB president Tom O’Mara:

The third issue Spinner and Justice 50 cent notes were printed in both red and green. Additionally, they

were printed with many different bronze back surcharge combinations and on different types of paper.

The total number of Friedberg #'s assigned to these 50 cent notes is 19 Spinners and 32 Justices. Of the

Spinners, 7 are red backs and 12 are green backs, and of the Justices, 15 are red backs and 17 are green

backs. There are NO reported or known Spinner red back inverts and ONLY one Justice red back

invert variety (Fr 1357, Milt #3R50.6a). Interestingly enough, there are estimated to be 10 known of

this red back Justice variety, making it the most common of all 3rd issue 50 cent inverts. The 50 cent

denomination came in 51 varieties of which 29 are green backs. The 29 varieties could create 87 potential

third issue 50 cent green back inverts (see charts). 45 of the 87 potential green invert varieties are known

(24) or reported to exist (21) of which 8 are unique. The total population of third issue 50 cent green

back inverts is estimated to be 57+ (32 Spinner, 25 Justice)

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

97

3rd issue - 50 CENTS - Spinner

Friedberg No. Inverted Back Engraving Inverted Back Surcharges Total Back Inverted

1324-1330 Unknown Unknown Unknown

1331 3R50.19p - Reported 3R50.19l - Reported (4) 3R50.19h - Reported

1332 - ‘1’ & ‘a’ 3R50.19q - Unique 3R50.19m - 3 Known 3R50.19i - Reported

1333 - ‘1’ 3R50.19r - Reported 3R50.19n - Reported 3R50.19j - Reported

1334 - ‘a’ 3R50.19s - Reported 3R50.19o - Reported 3R50.19k - Reported

1335 3R50.20h - Reported 3R50.20d - 4 Known Unknown

1336 -’1’ & ‘a’ 3R50.20i - Reported 3R50.20e - Reported Unknown

1337 -’1’ 3R50.20j - Reported 3R50.20f - Unique Unknown

1338 - ‘a’ 3R50.20k - Reported 3R50.20g - 2 Known Unknown

1339 -Type 2 rev Unknown 3R50.21h - 2 Known 3R50.21l – 2 Known

1340 -’1’ & ‘a’ Unknown 3R50.21i - 2 Known Unknown

1341 -’1’ Unknown 3R50.21j Unknown

1342 -’a’ Unknown 3R50.21k - Unique Unknown

3rd issue - 50 CENTS - Justice

Friedberg No. Inverted Back Engraving Inverted Back Surcharges Total Back Inverted

1343-1356 (red

back)

Unknown Unknown Unknown

1357 (red back) 3R50.6a - 10 Known Unknown Unknown

1358 Unknown Unknown Unknown

1359—’1’ & ‘a’ Unknown Unknown Unknown

1360—’1’ Unknown 3R50.13d - Reported Unknown

1361—’a’ Unknown Unknown Unknown

1362 3R50.10h - Reported 3R50.10d - 2 Known Unknown

1363—’1’ & ‘a’ Unknown 3R50.10e - Reported Unknown

1364—’1’ Unknown 3R50.10f - 4 Known Unknown

1365—’a’ Unknown 3R50.10g - 3 Known 3R50.10i - Reported

1366 Unknown 3R50.11d - 6 Known Unknown

1367—’1’ & ‘a’ Unknown 3R50.11e - Reported Unknown

1368—’1’ Unknown 3R50.11f - Reported Unknown

1369—’a’ Unknown 3R50.11g - Reported Unknown

1370 3R50.12h - 2-3 Known 3R50.12d - Unique 3R50.12l - unique

1371—’1’ & ‘a’ 3R50.12i - Reported 3R50.12e - Reported Unknown

1372—’1’ 3R50.12j - Reported 3R50.12f - Reported Unknown

1373—’a’ 3R50.12k - 2 Known 3R50.12g - 2 Known 3R50.12l - 4 Known

1373a—’S-2-6-4’ Unknown Unknown Unknown

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

98

a. Type 1 Inverted Back Engraving with and without Corner Surcharges. These types of error

reverses are found on Justice and Spinner fractionals designated in the charts in red fonts.

b. Type 1 Inverted Green Back Surcharges with and without Corner Surcharges. These types of

error backs are found on Justice and Spinner fractionals designated in the charts in blue fonts. Note how the

‘A-2-6-5’ corner surcharges are inverted along with the large ’50.’

c. Type 1 Total Inverted Back (Surcharges and Design) with and without Corner Surcharges.

These types of error backs are found on Justice and Spinner fractionals are designated in green fonts.

d. Type 2 Back with Inverted Surcharges. These types of error reverses are found on Spinner

fractionals only and designated in the charts in pink fonts.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * March/April 2019 * Whole No. 320_____________________________________________________________

99

e. Type 2 Total Inverted Green Back (Surcharges and Design). These types of error reverses are