Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

Plate Letters on Large Size NBNs--Peter Huntoon]

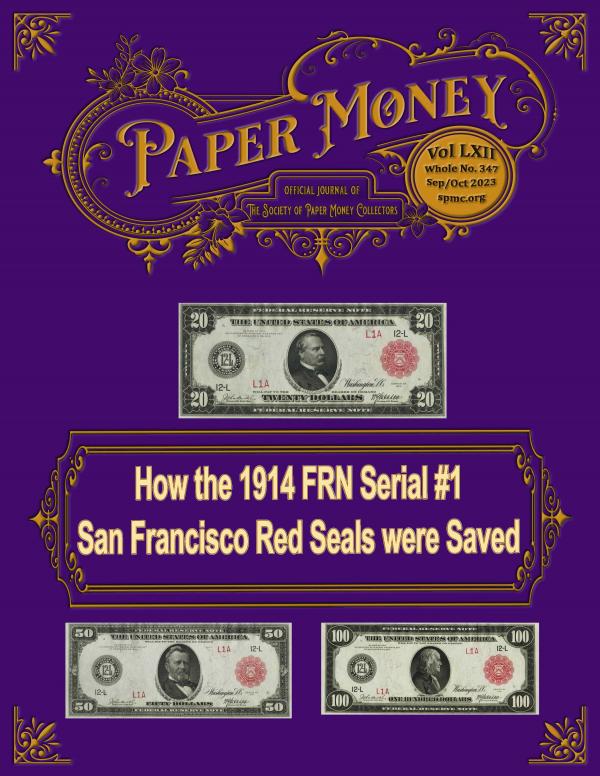

How the 1914 FRN Serial #1 Red Seals were Saved--Lee Lofthus

High Serial Discovery--Peter Huntoon

The Fate of Baugh's Cotton Mill in Alabama--Bill Gunther & Charles Derby

4th Issue Treasury Seal Plate Proof Sheets--Jerry Fochtman & Rick Melamed

Neither Chit Nor Chizzler--Terry Bryan

Altered 4th Printing Chemicograph Back--Peter Bertram

A Case of Mistaken Identity--Tony Chibarro

Montgomery Ward Catalog & U.S. Postal Notes Tame the Wild West--Bob Laub

UNESCO-Angola--Roland Rollins

official journal of

The Society of Paper Money Collectors

How the 1914 FRN Serial #1

San Francisco Red Seals were Saved

LEGENDARY COLLECTIONS | LEGENDARY RESULTS | A LEGENDARY AUCTION FIRM

Recent 2023 Prices Realized from

Stack’s Bowers Galleries

Include Your U.S. Currency in Our

November 2023 Showcase Auction – Consign Today!

Auction: November 14-17, 2023 • Consignment Deadline: September 18, 2023

CC-34. Continental Currency. May 9, 1776. $4.

PCGS Banknote Superb Gem Uncirculated 68 PPQ.

Realized: $18,000

T-45. Confederate Currency. 1862 $1.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Realized: $14,400

Fr. 1700. 1933 $10 Silver Certificate.

PCGS Banknote Superb Gem Uncirculated 67 PPQ.

Low Serial Number.

Realized: $99,000

Fr. 2210-Hlgs. 1928 Light Green Seal

$1000 Federal Reserve Note. St. Louis.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Realized: $43,200

Fr. 2402H. 1928 $20 Gold Certificate Star Note.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Realized: $38,400

Fr. 2405. 1928 $100 Gold Certificate.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 66 EPQ.

Realized: $192,000

Fr. 2407. 1928 $500 Gold Certificate.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Realized: $216,000

Fr. 2221-K. 1934 $5000 Federal Reserve Note.

Dallas. PCGS Banknote Choice Very Fine 35.

Realized: $174,000

Fr. 2301mH. 1934 $5 Hawaii Emergency

Star Mule Note. San Francisco.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 66 EPQ.

Realized: $52,800

Fr. 2200-Jdgs. 1928 Dark Green Seal

$500 Federal Reserve Note. Kansas City.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Realized: $43,200

Fr. 2201-A. 1934 Dark Green Seal

$500 Federal Reserve Note. Boston.

PCGS Banknote Superb Gem Uncirculated 68 PPQ.

Realized: $48,000

Fr. 2. 1861 $5 Demand Note.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Realized: $408,000

Contact Us for More Information Today!

West Coast: 800.458.4646 • East Coast: 800.566.2580 • Consign@StacksBowers.com

America’s Oldest and Most Accomplished Rare Coin Auctioneer

1550 Scenic Ave., Ste. 150, Costa Mesa, CA 92626 • 949.253.0916 • Info@StacksBowers.com

470 Park Ave., New York, NY 10022 • 212.582.2580 • NYC@stacksbowers.com

84 State St. (at 22 Merchants Row), Boston, MA 02109 • 617.843.8343 • Boston@StacksBowers.com

1735 Market St. (18th & JFK Blvd.), Philadelphia, PA 19103 • 267.609.1804 • Philly@StacksBowers.com

Info@StacksBowers.com • StacksBowers.com

California • New York • Boston • Philadelphia • New Hampshire • Oklahoma • Virginia

Hong Kong • Paris • Vancouver

SBG CDNGreensheet Nov2023 PR Consign 230901

320 Plate Letters on Large Size NBNs--Peter Huntoon

337 How the 1914 FRN Serial #1 Red Seals Were Saved--Lee Lofthus

344 High Serial Discovery--Peter Huntoon

346 The Fate of Baugh's Cotton Mill in alabama--Bill Gunther & Charles Derby

350 4th Issue Treasury Seal Plate Proof Sheets--Jerry Fochtman & Rick Melamed

357 Neither Chit nor Chizzler--Terry Bryan

361 Altered 4th Printing Chemicograph Backs--Peter Bertram

363 Book Review--Frank Clark

366 A Case of Mistaken Identity--Tony Chibbaro

379 Montgomery Ward Catalog & U.S. Postal Notes Tame the Wild West--Bob Laub

385 UNESCO-Angola--Roland Rollins

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

315

Columns

Advertisers

SPMC Hall of Fame

The SPMC Hall of Fame recognizes and honors those individuals who

have made a lasting contribution to the society over the span of many years.

Charles Affleck

Walter Allan

Doug Ball

Hank Bieciuk

Joseph Boling

F.C.C. Boyd

Michael Crabb

Forrest Daniel

Martin Delger

William Donlon

Roger Durand

C. John Ferreri

Milt Friedberg

Robert Friedberg

Len Glazer

Nathan Gold

Nathan Goldstein

James Haxby

John Herzog

Gene Hessler

John Hickman

William Higgins

Ruth Hill

Peter Huntoon

Glenn Jackson

Don Kelly

Lyn Knight

Chet Krause

Allen Mincho

Clifford Mishler

Barbara Mueller

Judith Murphy

Dean Oakes

Chuck O’Donnell

Roy Pennell

Albert Pick

Fred Reed

Matt Rothert

John Rowe III

Herb & Martha

Schingoethe

Hugh Shull

Glenn Smedley

Raphael Thian

Daniel Valentine

Louis Van Belkum

George Wait

D.C. Wismer

From Your President

Editor Sez

New Members

Uncoupled

Cherry Pickers Corner

Quartermaster

Obsolete Corner

Chump Change

Small Notes

Robert Vandevender 317

Benny Bolin 318

Frank Clark 319

Joe Boling & Fred Schwan 368

Robert Calderman 372

Michael McNeil 374

Robert Gill 376

Loren Gatch 378

Jamie Yakes 382

Stacks Bowers IFC

Pierre Fricke 315

FCCB 335

DBR Currency 335

Higgins Museum 335

PCGS-C 336

Fred Bart 343

Confederate Book 343

Bob Laub 343

Greysheet 345

Tom Denly 345

Lyn Knight 355

Kagins 360

ANA 386

PCDA IBC

Heritage Auctions OBC

Fred Schwan

Neil Shafer

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

316

Officers & Appointees

ELECTED OFFICERS

PRESIDENT Robert Vandevender II

rvpaperman@aol.com

VICE-PRES/SEC'Y Robert Calderman

gacoins@earthlink.net

TREASURER Robert Moon

robertmoon@aol.com

BOARD OF GOVERNORS

APPOINTEES

PUBLISHER-EDITOR

Benny Bolin smcbb@sbcglobal.net

ADVERTISING MANAGER

Wendell Wolka purduenut@aol.com

Megan Reginnitter mreginnitter@iowafirm.com

LIBRARIAN

Jeff Brueggeman

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

Frank Clark frank_clark@yahoo.com

IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT

Shawn Hewitt

WISMER BOOk PROJECT COORDINATOR

Pierre Fricke

From Your President

Robert Vandevender IIFrom Your President

Shawn Hewitt

Paper Money * July/August 2020

6

jeff@actioncurrency.com

LEGAL COUNSEL

Robert Calderman gacoins@earthlink.com

Matt Drais stockpicker12@aol.com

Mark Drengson markd@step1software.com

Jerry Fochtman jerry@fochtman.us

Pierre Fricke pierrefricke@buyvingagecurrency.com

Loren Gatch lgatch@uco.edu

Derek Higgins derekhiggins219@gmail.com

Raiden Honaker raidenhonaker8@gmail.com

William Litt billitt@aol.com

Cody Regennitter cody.reginnitter@gmail.com

Andy Timmerman andrew.timmerman@aol.com

Wendell Wolka purduenut@aol.com

In July, Nancy and I attended the Summer FUN sho . For the first time, my

niece Taylor and nephew Justin, accompanied by their parents, my sister Jennifer,

and Troy came to the show to see what it was all about. Nancy and I spent several

hours walking them around the floor showing them all of the exciting things one

can see at a money show. Both Justin and Taylor participated in the Treasure

Trivia Hunt where they went to various tables to answer a question and receive a

gift. They received many good items and learned a lot about numismatics. Justin

won a proof set on a wheel spin at one of the stops. Both received slabbed dollar

bills from PCGS. The SPMC didn’t have a table at the Summer FUN, but we will

be participating as one of the Treasure Trivia Hunt stops at the Winter FUN when

we hold our annual meetings and breakfast. Last year, our question to the children

was to explain what a star note signifies. We will be coming up with a different

question for this upcoming FUN. If you have children or grandchildren and have

never taken them to a major show, I highly recommend it.

Speaking of the Winter FUN, we have started planning for the various events

we hold during the show. We are planning for the breakfast meeting, designing

souvenir breakfast tickets, preparing for award presentations for both literary and

service awards, and arranging a speaker for our annual membership meeting. One

activity we are pursuing right now is donations for our annual Thomas Bain raffle,

always held during our breakfast meeting. It is a major fundraising activity for our

Society and helps offset the cost of breakfast. So, if you have a few numismatic

related items you would like to contribute, please seek out one of our Governors or

email for an address for shipment. Of course, we are a 501c3 organization and can

provide a receipt for anything donated if requested. Also, if you are interested in

doing an educational presentation, just let us know.

Mike Abramson sent out some interesting news about how currency will be

printed and packaged. It sounds like the notes in packs of new currency will no

longer be sequentially numbered, starting with the one dollar notes in 2023. This

will certainly change how people search for special serial numbers in the future.

Have you checked out the new Bank Note Lookup feature our Governor, Mark

Drengson, helped to develop. It is a very nice addition and open to the public. I

was using it at work the other day to look

up coworkers’ hometowns and many of the

non-collectors were interested and

impressed. Check it out at https://

banklookup.spmc.org/.

In July, the SPMC had a table at the

Long Beach Expo in California. We had a

steady stream of traffic at the table and

handed out many membership

applications. We will do it again at the

September show so if you are in the area,

please stop by and say hello.

At the recent ANA WFOM show, I had

the opportunity to meet with Ventris C.

Gibson, Director of the US Mint. Here is a

picture as she was presenting me with her

autographed card.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

317

Terms and Conditions

The Society of Paper Money Collectors (SPMC) P.O. Box 7055,

Gainesville, GA 30504, publishes PAPER MONEY (USPS 00‐

3162) every other month beginning in January. Periodical

postage is paid at Hanover, PA. Postmaster send address

changes to Secretary Robert Calderman, Box 7055, Gainesville,

GA 30504. ©Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc. 2020. All

rights reserved. Reproduction of any article in whole or part

without written approval is prohibited. Individual copies of this

issue of PAPER MONEY are available from the secretary for $8

postpaid. Send changes of address, inquiries concerning non ‐

delivery and requests for additional copies of this issue to

the secretary.

MANUSCRIPTS

Manuscripts not under consideration elsewhere and

publications for review should be sent to the editor. Accepted

manuscripts will be published as soon as possible, however

publication in a specific issue cannot be guaranteed. Opinions

expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect those of the

SPMC. Manuscripts should be submitted in WORD format via

email (smcbb@sbcglobal.net) or by sending memory stick/disk

to the editor. Scans should be grayscale or color JPEGs at

300 dpi. Color illustrations may be changed to grayscale at the

discretion of the editor. Do not send items of value.

Manuscripts are submitted with copyright release of the author

to the editor for duplication and printing as needed.

ADVERTISING

All advertising on space available basis. Copy/correspondence

should be sent to editor.

All advertising is pay in advance. Ads are on a “good faith”

basis. Terms are “Until Forbid.”

Ads are Run of Press (ROP) unless accepted on a premium

contract basis. Limited premium space/rates available.

To keep rates to a minimum, all advertising must be prepaid

according to the schedule below. In exceptional cases where

special artwork or additional production is required, the

advertiser will be notified and billed accordingly. Rates are

not commissionable; proofs are not supplied. SPMC does not

endorse any company, dealer, or auction house. Advertising

Deadline: Subject to space availability, copy must be received

by the editor no later than the first day of the month

preceding the cover date of the issue (i.e. Feb. 1 for the

March/April issue). Camera‐ready art or electronic ads in pdf

format are required.

ADVERTISING RATES

Editor Sez

Benny Bolin

Required file submission format is composite PDF v1.3

(Acrobat 4.0 compatible). If possible, submitted files should

conform to ISO 15930‐1: 2001 PDF/X‐1a file format standard.

Non‐ standard, application, or native file formats are not

acceptable. Page size: must conform to specified publication

trim size. Page bleed: must extend minimum 1/8” beyond

trim for page head, foot, and front. Safety margin: type and

other non‐bleed content must clear trim by minimum 1/2”.

Advertising c o p y shall be restricted to paper currency, allied

numismatic material, publications, and related accessories.

The SPMC does not guarantee advertisements, but accepts

copy in good faith, reserving the right to reject objectionable

or inappropriate material or edit copy. The SPMC

assumes no financial responsibility for typographical

errors in ads but agrees to reprint that portion of an ad in

which a typographical error occurs.

Benny

Space

Full color covers

1 Time

$1500

3 Times

$2600

6 Times

$4900

B&W covers 500 1400 2500

Full page color 500 1500 3000

Full page B&W 360 1000 1800

Half‐page B&W 180 500 900

Quarter‐page B&W 90 250 450

Eighth‐page B&W 45 125 225

Wow! Summer continues and Mother Nature continues to show

us how strong a lady she is and who is the boss. It is HOT even for

those of us in Texas. Being raised and working on a farm all my life,

I am usually not so bothered by the heat, but July and August have

really shown me how human (or how old) I really am.

From all indications, all aspects of the numismatic hobby are hot

also. Reports from regional shows, summer FUN and the ANA

WOFM, all had good and encouraging reports. I had to miss one of

my usual manistay shows, the Texas Numismatic Association again

this year as I had to accompany our high school choir as their nurse

to Hawaii. It was a good trip, but it was my third time going with our

choir and band and we did the exact same things as the prior two,

Pearl Harbor (which never gets old), the Polynesian Cultural Center,

the Dole Plantation. All was good and the kids had a good time.

I hope you all are going to attend Winter FUN this year. The

SPMC has seemingly made this our annual show as the IPMS was in

years past. It is a great show and we are again going to have a lot of

activities aimed at paper money. The show runs from January 4-7,

2024 at the Orange County Convention Center as usual. On Friday,

January 5, we hope to have a general membership meeting with an

educational presentation. We hope to hold our annual Tom Bain

Raffle and breakfast on Saturday January 6. More on these two will

be forcoming in the Nov/Dec issue of Paper Money. If you want to

donate items for the raffle, let one of the governors know and they

will be happy to take your items. This is also the time we will be

giving out our service and literary awards. Speaking of the latter, we

will be having our on-line voting for the literary awards in December

and presenting the winner at FUN. We will also have an or some

awards for paper money exhibt(s) as well.

Another of our stalwart members (two actually) were also

recently feted at the ANA WOFM. John and Nancy Wilson were

recognized with an ANA Philanthropy Award--Congrats to both!

The SPMC had a great ANA with many members award

recipents.

On a sad note, we were notified of the July passing of Glen Jorde

from Devils Lake, ND. He was a long time paper collector and

dealer and will be missed by the entire hobby.

Have a happy and safe summer and I hope to see you all

some day at a show although I dont generally get to many.

I hope you all have a great end of summer. Make plans to see us at

FUN '24 and remember to watch out for those kids as school is back

in session and they are probably not paying attention and watching/

texting on their phones instead of watching for you!

250

The Society of Paper Money

Collectors was organized in 1961 and

incorporated in 1964 as a non-profit

organization under the laws of the

District of Columbia. It is

affiliated with the ANA. The

Annual Meeting of the SPMC is

held in June at the International

Paper Money Show. Information

about the SPMC, including the

by-laws and activities can be

found at our website--

www.spmc.org. The SPMC does

not does not endorse any dealer,

company or auction house.

MEMBERSHIP—REGULAR and

LIFE. Applicants must be at least 18

years of age and of good moral

character. Members of the ANA or

other recognized numismatic

societies are eligible for membership.

Other applicants should be sponsored

by an SPMC member or provide

suitable references.

MEMBERSHIP—JUNIOR.

Applicants for Junior membership

must be from 12 to 17 years of age

and of good moral character. A parent

or guardian must sign their

application. Junior membership

numbers will be preceded by the letter

“j” which will be removed upon

notification to the secretary that the

member has reached 18 years of age.

Junior members are not eligible to

hold office or vote.

DUES—Annual dues are $39. Dues

for members in Canada and Mexico

are $45. Dues for members in all

other countries are $60. Life

membership—payable in installments

within one year is $800 for U.S.; $900

for Canada and Mexico and $1000

for all other countries. The Society

no longer issues annual membership

cards but paid up members may

request one from the membership

director with an SASE.

Memberships for all members who

joined the Society prior to January

2010 are on a calendar year basis

with renewals due each December.

Memberships for those who joined

since January 2010 are on an annual

basis beginning and ending the

month joined. All renewals are due

before the expiration date, which can

be found on the label of Paper

Money. Renewals may be done via

the Society website www.spmc.org

or by check/money order sent to the

secretary.

WELCOME TO OUR

NEW MEMBERS!

BY FRANK CLARK

SPMC MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

NEW MEMBERS 07/05/2023

NEW MEMBERS 08/05/2023

Dues Remittal Process

Send dues directly to

Robert Moon

SPMC Treasurer

104 Chipping Ct

Greenwood, SC 29649

Refer to your mailing label for when

your dues are due.

You may also pay your dues online at

www.spmc.org.

15586 David Netz Jr, Website

15587 David Leong, Frank Clark

15588 Michael Rocco, Website

15589 Zachary Askeland, Website

15590 Wayne Siebert, Website

15591 Karan Khandelwal, Website

15592 Remi Barbier, Website

15593 John Koar, Website

15594 Barbara Thompson, Rbt V.

15595 Carlos Zaragoza, Frank Clark

15596 Michael Sowizdrzal, Website

15597 Russ Frank, Robert Calderman

15598 Frank Harris, Robert Calderman

15599 Travis Bolton, Robert C.

15600 Charles Vincent, Frank Clark

15601 Len Ebersberger, Robert C.

15602 Steve Hose, Website

15603 Dimitriy Litvak, Frank Clark

REINSTATEMENTS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

None

15604 Aiden Shakirov, Website

15605 John Wyndham, Website

15606 William L. Brown, Robert Calderman

15607 Terrill M. Williams, Wendell Wolka

15608 Matthew Zimmermann, Website

15609 Elkader Auction House, Robert C.

15610 Danny Spungen, Derek Higgins

15611 Art Delgado, Derek Higgins

15612 Jessica Higgins, Derek Higgins

15613 James Ondak, Frank Clark

15614 Thomas Castloo, Derek Higgins

REINSTATEMENTS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

LM467 Andrew Timmerman, formerly

14986

LM468 Bradley Trotter, Frank Clark

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

319

The Paper

Column

by

Peter Huntoon

Plate Letters

on Large Size National Bank Notes and

the Maintenance and Replacement of Plates

PURPOSE

The purpose of this article is to explain the conventions that governed the lettering of subjects on

large size national bank note face plates. It is important to differentiate between replacement, altered and

reentered plates in order to determine when letters changed so the distinctions between these processes will

be discussed.

Incrementing the plate letters on replacement plates was a Bureau of Engraving and Printing

innovation. Only two cases have been recognized where replacement national bank note face plates bore

distinguishing markings made by the bank note companies.

LETTERING CONVENTIONS

Plate letters were always used on national bank note faces to differentiate between the subjects of

the same denomination on a given plate. The sequential advancement of letters on replacement plates was

a Bureau of Engraving and Printing innovation that commenced in 1878 during the Series of 1875. The

following plate lettering conventions became standardized by the time the Series of 1882 was introduced.

1. Each denomination had an independent lettering sequence.

2. The lettering began at A for each denomination with the start of each new series for each

bank.

3. Lettering for a given denomination advanced sequentially down the plate, and then from

plate to plate in the order in which the plates were made.

4. Plate letters reverted to A when new plates were made when: (a) the bank title was

changed as the result of a formal petition from the bankers and/or (b) an earlier charter

number was reassigned to the bank.

5. Plate letters were not changed on altered plates including: (a) Original Series to Series of

1875 conversions, (b) changed manufacturer imprints, (c) territorial to state conversions,

(d) addition of engraved signatures, (e) Comptroller-imposed title changes, or (f) title

changes limited to the removal of the word “The.”

6. Plate letters were advanced on existing Series of 1882 and Series of 1902 plates when they

were altered to the “or other securities” variety with the introduction of the date back

types in 1908.

The important fact here is that each denomination used by a bank had its own lettering sequence.

In cases where a given denomination appeared on different plate combinations in the same series, the letters

for that denomination walked sequentially through all the plates in the order in which the plates were made.

10-10-10-10 and 50-50-50-100 Series of 1882 and 1902 Plates

Three standardized plate formats were made available to banks for use in the Series of 1882 and

1902; specifically, 5-5-5-5, 10-10-10-20 and 50-100.

The 10-10-10-10 combination was introduced on July 23, 1906 as an option that bankers could

order. The purpose was to encourage the circulation of lower denomination notes, which were perceived

by Treasury officials to be under represented (Ridgely 1906).

The 50-50-50-100 was added to the mix during October 1910 in order to standardize the available

plate sizes at four subjects. Use of 50-100 plates was discontinued by the end of November, and they were

replaced with the new format.

Both of these changes had to be accommodated by the plate numbering system, so you will see that

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

320

both, especially the 10-10-10-10, led to very interesting lettering sequences for particular banks.

LETTERING SEQUENCE

Plate lettering is particularly interesting for banks with huge circulations because many plates were

required. Table 1 shows the lettering sequence for the 5-5-5-5 and 10-10-10-20 Series of 1902 plates for

The First National Bank of the City of New York (29). Notice the progression of lettering styles as the

alphabet was cycled: A, AA, A3, A4, etc. The subscript 2 was not used, rather the second pass through the

alphabet utilized the double letter style. For convenience, the doubled letter or number are referred to as

subscripts, however there is great variability in their placement next to the plate letters.

Figure 1. Double plate

letters were used

during the second

pass through the

alphabet. Numbered

letters were used

during the third and

higher passes through

the alphabet.

Table 1. Succession of plate letters on the Series of 1902 5-5-5-5 and 10-10-10-20 face plates

for The First National Bank of the City of New York, New York (29).

5-5-5-5:

A-B-C-D AA-BB-CC-DD A3-B3-C3-D3 A4-B4-C4-D4 A5-B5-C5-D5 A6-B6-C6-D6 A7-B7-C7-D7

E-F-G-H EE-FF-GG-HH E3-F3-G3-H3 E4-F4-G4-H4 E5-F5-G5-H5 E6-F6-G6-H6

I-J-K-L II-JJ-KK-LL I3-J3-K3-L3 I4-J4-K4-L4 I5-J5-K5-L5 I6-J6-K6-L6

M-N-O-P MM-NN-OO-PP M3-N3-O3-P3 M4-N4-O4-P4 M5-N5-O5-P5 M6-N6-O6-P6

Q-R-S-T QQ-RR-SS-TT Q3-R3-S3-T3 Q4-R4-S4-T4 Q5-R5-S5-T5 Q6-R6-S6-T6

U-V-W-X UU-VV-WW-XX U3-V3-W3-X3 U4-V4-W4-X4 U5-V5-W5-X5 U6-V6-W6-X6

10-10-10-20:

A-B-C-A AA-BB-CC-I A3-B3-C3-Q A4-B4-C4-AA A5-B5-C5-II

D-E-F-B DD-EE-FF-J D3-E3-F3-R D4-E4-F4-BB D5-E5-F5-JJ

G-H-I-C GG-HH-II-K G3-H3-I3-S G4-H4-I4-CC G5-H5-I5-KK

J-K-L-D JJ-KK-LL-L J3-K3-L3-T J4-K4-LL-DD J5-K5-L5-LL

M-N-O-E MM-NN-OO-M M3-N3-O3-U M4-N4-O4-EE M5-N5-O5-MM

P-Q-R-F PP-QQ-RR-N P3-Q3-R3-V P4-Q4-R4-FF P5-Q5-R5-NN

S-T-U-G SS-TT-UU-O S3-T3-U3-W S4-T4-U4-GG

V-W-X-H VV-WW-XX-P V3-W3-X3-X V4-W4-X4-HH

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

321

In what is a measure of great financial prowess, The First National Bank of the City of New York

(29), reached $5 Series of 1902 plate A7-B7-C7-D7, the highest format found on any plate. This plate was

certified for use December 10, 1928. The last 5-5-5-5 delivery for the bank from the Bureau of Engraving

and Printing to the Comptroller occurred on July 6, 1929, and ended with sheet serial B179083. The last

sheet sent to the bank was B123785, yielding an astonishing total of 2,396,985 sheets of Series of 1902

fives. Over 55,000 of the last of the sheets were not sent to the bank, so it appears that no notes from the

A7-B7-C7-D7 plate got out, provided they were even printed. I have never seen one.

The highest format used on a 10-10-10-20 plate was P5-Q5-R5-NN for the same bank on a Series of

1902 plate completed August 6, 1928. The last of that combination was delivered to the Comptroller July

1, 1929, and bore serial A321021. The last issued to the bank was A300533, yielding a total of 1,731,253

Series of 1902 10-10-10-20 sheets.

Letter subscripts were used on Series of 1882 plates for a number of banks; however, the numerical

subscripts were never reached in that series. We could have seen a Series of 1882 plate lettered A3-B3-C3-

D3 had The National Bank of Commerce in New York (733) required just one more Series of 1882 5-5-5-

5 plate!

Notice from Table 1 how the lettering sequence usually did not include the full alphabet. The sixth

format in the succession of 5-5-5-5 plates was U-V-W-X. The letters Y and Z were skipped so that the

seventh format was AA-BB-CC-DD. Thus, the style of letting was homogeneous on the plate instead of the

heterogeneous Y-Z-AA-BB.

As shown on Table 1, the letters Y and Z also were avoided in successions of 10-10-10-20 plates.

The eighth format in that succession was V-W-X-H. The letters Y and Z were skipped on the $10s on the

ninth format, so the plate was lettered AA-BB-CC-I. Here, the styles of letters used on the $10s remained

homogeneous, but notice that the $20 was consecutive from the preceding format. The 24th format was V3-

W3-X3-X. The Y was not used on the $20 on the next plate. Rather, the Y and Z were once again skipped

so the 25th format became A4-B4-C4-AA!

Plate lettering was far more interesting when a large bank utilized a mix of 10-10-10-20 and 10-

10-10-10 plates. A good example involves the listing on Table 2 for the Series of 1882 plates for San

Francisco (5105), a bank that had a title change. Notice for this bank that plate lettering reverted to A after

the title change. More interesting, follow the progression of plate letters for the $10s and $20s through the

succession of 10-10-10-20 and 10-10-10-10 plates.

Figure 2. The highest plate letter used on a national bank plate was D7 on a Series of 1902

plate for The First National Bank of the City of New York (29). Notes printed from the plate

containing this subject may not have reached circulation, owing to not having been printed or

being canceled at the end of the large note era. National Numismatic Collection, Smithsonian

Institution photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

322

USE OF Y AND Z

The letters Y and Z were reached only on $10s, and only when a bank used just the right mix of

10-10-10-10 and 10-10-10-20 plates. Only two Series of 1882 issuing banks had plates made with Y and Z

position letters, both during their date back issues; specifically, The National Bank of Commerce in St.

Louis (4178) and National Shawmut Bank of Boston (5155). Seven 1902-issuers received them in the Series

of 1902; specifically, charters 104, 121, 733, 891, 1111, 1290 and 1370.

Table 2. Plate Letters on the Series of 1882 face plates for The Nevada

and The Wells Fargo Nevada National Banks of San Francisco,

California (5105). Notice how the plate letters on the $10 Subjects

thread through the 10-10-10-10 and 10-10-10-20 combinations.

5-5-5-5 10-10-10-10 10-10-10-20 50-100 Date Certified

The Nevada National Bank of San Francisco

Series of 1882 brown back face plates:

A-A Jan 22, 1898

A-B-C-A Jan 22, 1898

A-B-C-D Jun 21, 1900

D-E-F-B Aug 12, 1902

E-F-G-H Aug 19, 1902

I-J-K-L Oct 6, 1902

G-H-I-C Dec 7, 1904

The Wells Fargo Nevada National Bank of

A-B-C-D May 22, 1905

A-B-C-A May 23, 1905

E-F-G-H Jul 7, 1905

D-E-F-B Aug 9, 1905

G-H-I-J Sep 15, 1906

K-L-M-N Oct 11, 1907

Series of 1882 date back face plates:

I-J-K-L Sep 14, 1908

O-P-Q-C Sep 15, 1908

R-S-T-D Sep 14, 1908

U-V-W-X Sep 15, 1908

M-N-O-P Nov 8, 1908

Q-R-S-T Oct 29, 1909

AA-BB-CC-DD Oct 29, 1909

U-V-W-X Oct 9, 1912

AA-BB-CC-DD Sep 12, 1914

Series of 1882 value back face plates:

EE-FF-GG-HH Mar 28, 1916

EE-FF-GG-HH Mar 29, 1916

II-JJ-KK-LL Aug 30, 1916

MM-NN-OO-PP Mar 20, 1917

II-JJ-KK-LL Mar 22, 1917

The following Wells Fargo Nevada face plates were altered from brown to date

backs and relettered as shown:

Combination Brown Back Date Back

5-5-5-5 E-F-G-H I-J-K-L

10-10-10-10 K-L-M-N U-V-W-X

10-10-10-20 A-B-C-A O-P-Q-C

10-10-10-20 D-E-F-B R-S-T-D

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

323

Although theoretically possible, the letters Y and Z never were used in a 50-100/50-50-50-100 mix

because no bank required the requisite number of plates.

PLATE LETTERS

Attractive, ornate letters were the standard on most first plates in the Original Series through Series

of 1882. Early on, the styles of the plate letters found on some 10-10-10-10 and 20-20-20-20 plates differed

to distinguish those combinations. The letters on the earliest 10-10-10-10 Original Series plates were

oversize, and they were carried forward when those plates were altered into Series of 1875. Similarly, the

lower left plate letters on some 20-20-20-20 Series of 1875 plates appear ghost like to distinguish notes

from that combination.

The letters on some early Series of 1875 10-10-10-10 and 10-10-10-20 replacement plates were

italicized. Plain open letters were adopted for use on 10-10-10-20 Series of 1882 replacement plates. The

plain letters also were used on all 10-10-10-10 Series of 1882 plates first introduced in 1906, and on all re-

lettered 10-10-10-20 plates when the brown back face plates were altered it carry the “or other securities”

security clause required for the date back faces.

REPLACEMENT, ALTERED AND REENTERED PLATES

The processes of replacing, altering and reentering plates must be distinguished in order to bring

clarity to this discussion.

Replacement plates were entirely new plates that were manufactured to replace worn plates, or

plates that were purged for having inartistic title blocks. The plate letters on the various subjects on

replacement plate were always advanced from those on previous plates beginning in 1878.

Altered plates were existing plates on which design elements were changed. The rule for altered

plates was that plate letters were left unchanged. However, there was one huge group of exceptions.

Lettering of the subjects was advanced when Series of 1882 brown back and 1902 red seal faces were

altered into their date back forms.

Reentered plates were worn plates upon which design elements were repressed from rolls to

refurbish details. The plate letters on reentered plates were left unchanged, but occasionally moved slightly.

Figure 3. Varieties of letters used on early

series $10 and higher plates. Left column:

(a) standard size plate letters used on

most Series of 1882 and earlier plates, (b)

oversize letters on the earliest 10-10-10-

10 Original Series plates, (c) italicized

plate letters on early 10-10-10-10 and 10-

10-10-20 replacement plates, (d) plain

upright letters on Series of 1882

replacement plates. Right column: top is

the standard plate letter used on most

Series of 1882 and earlier plates, bottom

is a ghost-like plate letter used on some

Series of 1875 20-20-20-20 plates.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

324

REPLACEMENT PLATES

The problem of worn plates plagued the national bank note printings from the beginning. Only two

cases are known where special markings were used to identify Original Series replacement plates.

The second 5-5-5-5 Original Series plate for The Tenth National Bank of the City of New York

(307) has a small numeral 2 engraved under the lower right plate letter on all four subjects. It was prepared

by the Continental Bank Note Company.

Similarly, the second 1-1-1-2 for The Mechanics National Bank of the City of New York (1250)

prepared by the American Bank Note Company has 2s next to the left plate letters on the $1s and both plate

letters on the $2.

The other Original Series replacement plates were duplicates down to the same plate letters.

Figure 4. The number 2 was

engraved below the lower right

plate letters to distinguish the

subjects on the Original Series

5-5-5-5 replacement plate made

for The Tenth National Bank of

the City of New York, New

York (307).

Figure 5. A numbered Original Series replacement plate was made for The Mechanics National Bank of the

City of New York (1250) that was altered into a Series of 1875 plate by the BEP. Left detail is of the numbered

position letters on the left side of the $1s. Right detail is of the numbered position letters on the $2s.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

325

The identification of replacement plate evolved once the Bureau of Engraving and Printing took

over responsibility for making and maintaining the plates. The first replacement plates that were made by

the Bureau to replace existing Series of 1875 plates had incremented plate letters and updated Scofield-

Gilfillan signatures, that reveal that they were made after April 1, 1878. Advancing the plate letters was a

Bureau of Engraving and Printing innovation. A good example is the E-F-G-H 5-5-5-5 Series of 1875 for

The Second National Bank of Springfield, Massachusetts (181). It replaced an A-B-C-D with the Allison-

New combination.

Some replacement plates were prepared instead of altering worn Original Series plates into Series

of 1875 plates. The 50-100 plate for the Gallatin National Bank of the City of New York (1324) is an

example that was certified May 25, 1878 and carried Scofield-Gilfillan signatures and incremented B-B

plate letters.

The practice of updating signatures on replacement plates ceased during 1878. From then on, every

key piece of information remained the same as on the previous plate, although the styles or positions of the

various design elements could be changed or rearranged, and the bank note company imprint could be

replaced with a Bureau imprint. The plate letters were variable items.

The strictness with which Bureau employees adhered to advancing the plate letters is illustrated by

a couple of glitches that converged on the same day. The $5 A-B-C-D Series of 1882 plate for The First

National Bank of Michigan City, Indiana (2747), made in 1882, with a patented letter layout was replaced

by a circus poster variety certified on January 22, 1887. The problem was that the new plate was lettered

A-B-C-D, not E-F-G-H. This mistake was spotted, the letters were corrected by altering the plate, and the

corrected plate was certified January 28, 1887.

However, on January 28th, a replacement $5 Series of 1882 face for The National Shoe and Leather

Bank of the City of New York (917) was submitted for approval that replaced another patented letter A-B-

C-D plate made two years earlier. This replacement also was mis-lettered A-B-C-D. The error was caught

immediately because everyone concerned was on the alert thanks to the Michigan City situation, and the

plate was not certified. In fact, it was fixed and certified that very same day. The haste with which it was

altered indicates that someone probably got an earful!

ALTERED PLATES

Alterations did not result in changes to the plate letters except when the Series of 1882 and 1902

face plates were altered into the date back varieties by changing the security clause.

The altering of plates was a very common cost-effective occurrence. Anything on the plate could

be changed. The most interesting alteration order that I found was the following to the Bureau from

Comptroller Knox, dated May 7, 1877.

Please change the plate 5.5.5.5 prepared for The Farmers National Bank of Mattoon, Illinois, which plate

was ordered to be prepared in letter from this office February 14, 1876, to “The Farmers National Bank of

Platte City,” Platte City, Missouri. Transfer to bear date May 25, 1877, charter number 2356.

There was no Farmers National Bank of Mattoon, Illinois. The original order was a mistake and

the Comptroller was saving money by having the plate altered instead of having an entirely new one made.

The point is that even wholesale alterations were undertaken and at the time were considered routine.

Conversion to Series of 1875

A common alteration was the conversion of Original Series plates into Series of 1875 forms. The

alterations included changing the Treasury signatures, adding or removing manufacturer imprints, and

extending vignettes to the borders.

Replacing Imprints

A common alteration was to replace the bank note company imprints with that of the Bureau on

Series of 1875 and 1882 plates. Those alterations also involved removing the words “Printed at the Bureau,

Engraving & Printing, U. S. Treasury Dept” from plates containing them.

Territorial to State Conversions

A common alteration in all series was the conversion of territorial plates into state plates. In these

cases, the state replaced the territorial designation, and the Treasury signatures and plate dates were updated.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

326

Figure 6. When the replacement plate (center note) was made, it was mistakenly lettered A-B-C-D.

The same error had just been made on a plate for Michigan City, Indiana. Notice from the certification

dates that the plate was re-lettered the day the error was discovered! National Numismatic Collection,

Smithsonian Institution photos.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

327

Bank Signatures

Engraved bank signatures were added to many Series of 1902 plates beginning in 1922. This

alteration also involved removing the line under the signatures.

Comptroller-Imposed Title Changes

There were a few instances in the Series of 1882 and 1902 when the postal locations written in

script in the title blocks were changed by means of mid-series Comptroller-imposed title changes to clarify

the locations of banks. All accommodated changes in the name of the town.

The Series of 1882 cases involved Mystic River/Mystic, Connecticut (645), Great

Falls/Somersworth, New Hampshire (1183), North Auburn/Auburn, Nebraska (3343), New

Tacoma/Tacoma, Washington Territory (2924) and Geneva/Lake Geneva, Wisconsin (3135). The 1902

cases involved Allegheny/Pittsburgh (198 and 776).

The existing plates were altered in all cases except for Mystic River/Mystic, Connecticut. The

Mystic bank got new plates. On the others, the protocol followed was not to change the plate letters because

the changes classified as an alteration to an existing plate with the single anomalous exception of the Series

of 1902 10-10-10-20 plate for The First National Bank of Allegheny (198). The letters were advanced on

that plate.

Figure 7. A new title block and modernized will pay line was used on the replacement plate

for The Putnam County National Bank of Carmel, New York (976). Insufficient numbers of

notes of this type were issued from the bank to warrant replacing the first plate as a result of

wear. The replacement plate was prepared in 1897 to replace a patented letter title block

layout with an artistic layout. National Numismatic Collection, Smithsonian Institution

photos.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

328

Table 3. Plate lettering for the Series of 1902 face plates for The First and Second

National Banks of Allegheny, Pennsylvania (198, 776) on which the post office

location was changed to Pittsburgh.

Script

Type 5-5-5-5 10-10-10-20 Location Date Certified Comment

First National Bank (198):

1902RS A-B-C-A Allegheny Feb 26, 1903 altered to D-E-F-B

1902DB D-E-F-B Allegheny Aug 24, 1908 altered to Pittsburgh G-H-I-C

1902DB G-H-I-C Pittsburgh Mar 15, 1909 letters should not advance

1902DB A-B-C-D Pittsburgh Mar 18, 1909 new plate

Second National Bank (776):

1902RS A-B-C-A Allegheny Jan 5, 1905 altered to D-E-F-B

1902DB D-E-F-B Allegheny Aug 25, 1908 altered to Pittsburgh D-E-F-B

1902PB A-B-C-D Allegheny Oct 31, 1917 altered to Pittsburgh A-B-C-D

1902PB A-B-C-D Pittsburgh Dec 20, 1917

1902DB D-E-F-B Pittsburgh Dec 20, 1917

Figure 8. The script location on the plate for The First National Bank of Allegheny,

Pennsylvania (198), was altered by means of a Comptroller-imposed title change to show the

new post office location after Allegheny was incorporated into Pittsburgh. The lettering was

advanced on this plate despite the convention that letters should be left unchanged on altered

plates. This is the only known case of advanced letters on an altered plate outside of “or other

securities” alterations. National Numismatic Collection, Smithsonian Institution photos.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

329

The Allegheny exception almost makes sense in the context of the times during which the alteration

was carried out. The plate was originally made in 1903 as a red seal face lettered A-B-C-A. It was altered

into a date back face in 1908, and re-lettered D-E-F-B. Bureau of Engraving and Printing personnel still

were heavily involved in the date back conversions when the script Allegheny was changed to Pittsburgh

in March 1909. Without drawing a distinction, they advanced the letters to G-H-I-C on the Pittsburgh plate

as well. This is the only example I have seen where letters were advanced on an altered plate outside of the

date back conversions. See Table 3.

Removal of the Word “The”

A few bankers dropped the word “The” from their titles, mostly following mergers. If such a title

change occurred mid-series, the expedient way to handle the change was to simply alter the existing plates

by removing “The” from them.

Date Back Alterations

The Emergency Currency Act of May 30, 1908, required that all Series of 1882 and 1902 face

plates include the clause “or other securities.” Approximately 10,000 plates were altered to comply with

this act. The plate letters on those plates were advanced as they were altered. This represents the only

situation when plate letters were supposed to change on altered plates.

Table 4 shows the interesting result when the Series of 1882 brown back 10-10-10-20 A-B-C-A

and 10-10-10-10 D-E-F-G plates for The First National Bank of Chickasha, Oklahoma (5431) were altered

to their date back forms. The altered 10-10-10-20 was mis-lettered D-E-F-B. The letters D, E and F on the

$10s had already been used on the 10-10-10-10 brown back plate.

The error was discovered, so the $10 subjects on the plate were re-lettered L-M-N. Sufficient time

had elapsed between the time the error was made and corrected to allow printings to have been made, but

they weren’t. The 10-10-10-20 date back version of the plate never was sent to press.

REENTERED PLATES

Reentering was very common throughout the large size national bank note issues because it cost

effectively prolonged the life of plates. Fundamental design elements often were modified during Series of

1875 and 1882 reentries. Modifications included changing manufacturer imprints, using different

engravings for the vignettes, and even updating the Treasury signatures for a short period in 1878.

Reentry in the Series of 1902 mostly involved reentering the portraits because they were the first

design element to exhibit wear. Typical Series of 1902 plates lasted for about 35,000 impressions. However,

as one example, the Series of 1902 $5 plates for The First National Bank of the City of New York (29)

averaged more than 60,000 impressions. Such high yields indicate that many of those plates were reentered,

sometimes more than once.

Table 4. Plate lettering error on a Series of 1882 date back

10-10-10-20 face plate for The First National Bank of

Chickasha, Oklahoma (5431).

10-10-10-20 10-10-10-10 Date Certified Comment

Indian Territory Series of 1882 brown back face plates:

A-B-C-A Aug 24, 1900

D-E-F-G Sep 8, 1906

Oklahoma Series of 1882 brown back face plates:

A-B-C-A Jan 28, 1908 altered to D-E-F-B

D-E-F-G Jan 28, 1908 altered to H-I-J-K

Oklahoma Series of 1882 date back face plates:

H-I-J-K Dec 12, 1908

D-E-F-B May 14, 1909 $10s mislettered

L-M-N-B Aug 4, 1909 $10s relettered

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

330

Figure 9. This Chickasha Series of 1882 brown back 10-10-10-20 plate was mis-lettered

D-E-F-B when it was altered into a date back, because D-E-F-G already had been used on

a 10-10-10-10 brown back plate. The $10s had to be re-lettered L-M-N as shown. Neither

the mis-lettered nor corrected plate was used. National Numismatic Collection,

Smithsonian Institution photos.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

331

Figure 10. The first and third titles for this Buffalo, New York, bank were identical. A

new plate was made for each title, so these three notes—all from the C plate position—are

from different plates. Notice that the plates for the first and third titles were identical in

every respect! Photos courtesy of Heritage Auction Archives.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

332

IDENTICAL SERIES OF 1902 PLATES

The convention of copying the plate date from the most recent plate onto new title plates, which

went into effect April 12, 1919, led to the manufacture of a few totally identical Series of 1902 face plates.

Here is how this happened.

In cases where there were multiple title changes from 1919 forward, the pre-1919 date on the early

plate was propagated forward onto all the new plates. Consequently, if the bank readopted the same title as

appeared on the pre-1919 plate, the new plate had the same: (1) title, (2) plate date and (3) Treasury

signatures. Plate lettering also would start at A for each denomination because the convention was to restart

lettering with the advent of a new title.

The only variable could be the wording in the security clause. Post-April 1919 plates utilized

“deposited with the U. S. Treasurer” rather than “or other securities.” The only way the pre-1919 plate

could have a Adeposited with the U. S. Treasurer@ security clause would for it to have been a red seal face

made prior to May 30, 1908, or a blue seal face made after June 30, 1915.

Two questions arise: (1) did all of these factors, including the same security clause, converge, and

(2) if they did, how were the new plates handled? Everything did align for two banks: Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania (539) and Buffalo, New York (11768). In each case, the first and third titles were identical.

Bureau personnel used the pre-1919 plates bearing the common title as models and duplicated every detail

when making the new plates.

The first use of The Philadelphia National Bank (539) title occurred on the Series of 1902 red seal

5-5-5-5 A-B-C-D and 10-10-10-20 A-B-C-A face plates in 1904. One would expect the Bureau personnel

to reuse the old plates in 1928, but this was impossible because they had been destroyed. New plates had

to be prepared. Printings for the first and third titles respectively involved red seals and blue seal plain

backs, making for colorful matched pairs.

The case of the duplicate use of The Community National Bank of Buffalo (11768) title is even

more interesting. The first Series of 1902 5-5-5-5 A-B-C-D and 10-10-10-20 A-B-C-A plates were made

for that bank in 1920 upon being chartered. The title was changed to the Community-South Side National

Bank in 1925, and back to The Community National Bank in 1926. Plates were made for each of these

titles, and plate lettering began at A for each denomination. The plates bearing the first and third titles were

identical in every respect. All were used to print Series of 1902 blue seal plain backs.

MULTIPLE PLATE USAGE FOR LARGE BANKS

The demand for notes for the largest banks was so great that more than one plate of a given

combination was in use at the same time. An example involves the Series of 1882 brown back and date

back issues for The Nevada National Bank of San Francisco. Notice from Table 2 that two 10-10-10-20

plates were altered into date back plates in 1908, revealing that both were in active use at that time.

Consequently, it is possible to find pairs of notes from the same plate combination on which the plate letters

appear to be out of order relative to the serial numbers.

David Grant showed me a pair of $5 Series of 1902 plain backs from The National Bank of

Commerce in St. Louis (4178) that carry serials 763447 and 785878, respectively from positions D3 and Xx

on the 13th and 12th 5-5-5-5 plates. Obviously those two plates were on the presses at the same time.

OUT-OF-ORDER USAGE OF PLATES

Robert Kvederas showed me a case where the Series of 1902 5-5-5-5 plate letters for The Textile

National Bank of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (7522) followed this progression: (1) plate A-B-C-D for red

seals from 1905-1908; (2) altered plate E-F-G-H for blue seal date backs 1908-1914, (3) replacement plate

I-J-K-L for blue seal date and plain backs 1914-1924, and finally (4) E-F-G-H again for the blue seal plain

backs 1924 to 1929.

The proofs revealed that when the I-J-K-L plate showed wear in 1924, the old E-F-G-H plate was

reentered instead and restored to service. The result was out of sequence lettering relative to the serial

numbers on the late blue seal plain backs. This phenomenon occurs in the issues for other banks as well,

but it is unusual.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

333

CONVENTION WENT OUT THE WINDOW

A Comptroller-imposed title change caused a particularly unusual situation to occur with the 5-5-

5-5 and 10-10-10-20 Series of 1882 plates for The Mystic River National Bank, Mystic River, Connecticut

(645). Mystic River lost its post office in 1887, then it location was renamed West Mystic, and the post

office in Mystic Bridge that served it after 1887 was renamed Mystic in 1890. The Comptroller=s clerks

imposed a title change in 1899 to reflect all of this! The script post office location of Mystic River was

accordingly changed to Mystic.

Breaking with tradition, they ordered new plates to reflect the change, instead of simply having

Mystic River changed to Mystic in the postal location on the existing plates. The plate letters on the old

plates would not have been changed had they been altered.

The title change in effect was being treated as a formal title change. With new plates being prepared

to mark the event, plate lettering should have started over at A for each denomination. This didn’t happen.

The letters on the new plates were respectively advanced to E-F-G-H and D-E-F-B on the 5-5-5-5 and 10-

10-10-20 plates.

The lettering treated the plates as replacement plates. The letters on them were totally out of

character for new plates made to reflect a formal title change or for altered plates to reflect a Comptroller-

imposed title change. The outcome simply was strange and unprecedented!

Figure 11. Normally a Comptroller imposed title change to update the postal location would

have been handled by altering Mystic River to Mystic on the plate (top) with no change in the

plate letters. Instead, a new plate was ordered as if the change was formally requested by the

bankers, which would have caused lettering to start over (bottom). Neither protocol was

followed in this interesting instance. National Numismatic Collection, Smithsonian

Institution photos.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

334

SUMMARY

Plate letters were used on national bank notes in order to distinguish between subjects of the same

denomination on a sheet. Original Series replacement plates were prepared by the bank note companies and

were virtually identical to those that they replaced right down to the use of identical plate letters. The

sequential advancement of plate letters on replacement plates was a Bureau of Engraving and Printing

innovation that commenced in 1878 within the Series of 1875.

Plates were commonly altered in order to display new information. The convention was not to

change plate letters on altered plates, the one exception being that lettering was advanced on Series of 1882

and 1902 face plates when the securities clause was altered so they could be used to print date backs.

The plate letters were left as was when plates were reentered.

REFERENCES CITED AND SOURCES OF DATA

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 1875-1929a, Certified proofs of national bank note face and back plates: National Numismatic

Collections, Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 1875-1929b, National bank note face plate history ledgers: Record Group 318, U. S. National

Archives, College Park, MD

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, various dates, Correspondence to and from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing: Record Group

318, U. S. National Archives, College Park, MD.

Ridgely, William B., July 23, 1906, Circular letter to the cashiers of national banks advising them of the availability of 10-10-10-

10 plates: Comptroller of the Currency form 2116, Washington, DC.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

335

You Collect. We Protect.

Learn more at: www.PCGS.com/Banknote

PCGS.COM | THE STANDARD FOR THE RARE COIN INDUSTRY | FOLLOW @PCGSCOIN | ©2021 PROFESSIONAL COIN GRADING SERVICE | A DIVISION OF COLLECTORS UNIVERSE, INC.

PCGS Banknote

is the premier

third-party

certification

service for

paper currency.

All banknotes graded and encapsulated

by PCGS feature revolutionary

Near-Field Communication (NFC)

Anti-Counterfeiting Technology that

enables collectors and dealers to

instantly verify every holder and

banknote within.

VERIFY YOUR BANKNOTE

WITH THE PCGS CERT

VERIFICATION APP

How the 1914 FRN

Serial No. 1

San Francisco Red Seals

Were saved

by Lee Lofthus

On April 29, 2011, Heritage Auctions sold a complete Serial Number 1 denomination set

of Series of 1914 Federal Reserve notes from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Documents at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, reveal how these phenomenal

notes came to be saved over a hundred years ago.

Figure 1. If you think a number 1 1914 red seal Federal Reserve note is a show stopper, think

about having a denomination set of them from the same district! Heritage Auction archives photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

337

The Series 1914 Federal Reserve notes were new in every sense. They were an entirely

new class of bank currency. The designs were distinctly modern. Their backing provided an

elasticity that gold certificates, silver certificates, and national bank notes could not match. As the

first appointees of the just-created Federal Reserve Board began their jobs, one of the members

wanted to save the very first notes from his hometown district.

Creation of the Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve Act was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on December

23, 1913. The Act established a central banking function for the nation with a governing board of

seven members: five appointed by the President with the approval of the Senate, plus the Secretary

of the Treasury and the Comptroller of the Currency as ex officio members. See Figure 2.

The locations of the now-familiar twelve Federal Reserve districts were decided upon by

Figure 2. The first members of the Federal Reserve Board, 1914. Back row, left to right: banker Paul

M. Warburg; Comptroller of the Currency John Skelton Williams; banker William P. G. Harding;

professor Adolph C. Miller. Front row: attorney Charles Sumner Hamlin, Governor of the Board

(now called Chair); Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo; Vice Governor and railroad

executive Frederic A. Delano. Adolph Miller, upper right, sought to save the No. 1 Federal Reserve

notes from his hometown of San Francisco. Library of Congress photo, control no. (LCN)

2014698007.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

338

April of 1914, but the banks did not begin operation until November 16, 1914. The delay was

caused in part by waiting for adequate supplies of Federal Reserve notes to be on hand when the

banks opened. Meanwhile, the five appointed members of the Board were sworn into office on

August 10, 1914.

Federal Reserve Notes

Section 16 of the Act provided for the issue of Federal Reserve notes. The notes were to

be identified by a distinctive letter and serial number convention assigned to each Federal Reserve

district. They were backed by United States bonds bearing the circulation privilege, but unlike

national bank notes, the Federal Reserve banks could issue currency in excess of their capital stock,

thus providing the desperately needed elasticity to the notes.

Figure 3. The first $5 and $10 notes were issued to the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

on December 10, 1914. The higher denominations shown above arrived months later, delaying

delivery of Miller’s set of notes until May 1915. Heritage Auctions archive photos.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

339

The new Federal Reserve notes were redeemable in

gold on demand at the Treasury building in Washington or in

gold or lawful money at any Federal Reserve bank. Issue of the

notes was the responsibility of the Federal Reserve “agent” in

each district. The chairman of each of the twelve district banks

served as the agent for his respective bank.

Many numismatic references describe the Series of

1914 Federal Reserve notes as plain in appearance. The head

of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing thought just the

opposite. In his annual report for 1914, Joseph E. Ralph, the

bureau’s director, said “It is believed that the designs for these

new notes are the most suitable and the most beautiful that have

ever been placed on our paper issues. The backs are even more

artistic than the faces and at the same time afford the greatest

possible protection again counterfeiting.”

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco opened

with less than 25 employees working in rented office space in

the back of the

old Merchants

National Bank

of San Francisco. It had been only eight years since

the great 1906 earthquake devastated San

Francisco, but the city rebuilt and continued its

progress as a dynamic banking center, and it

became the choice for the western-most district.

The bank served the states of California, Idaho,

Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and most of

Arizona. It also served the territories of Alaska and

Hawaii.

The Chairman and Agent for the bank was

John C. Perrin, a Pasadena, California, banker who

had worked for the passage of the Federal Reserve

legislation.

Adolph C. Miller

Adolph Caspar Miller was appointed a

member of the first Federal Reserve Board on

August 10, 1914, and served until February 3, 1936.

He was born in San Francisco in 1866. Miller

earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of

California, and a master’s degree from Harvard

University. He spent over 20 years teaching, first

economics at Harvard, then history and politics at

the University of California, and later finance at

Cornell and then the University of Chicago.

Figure 4. John Perrin,

Chairman and Federal Reserve

Agent for the Federal Reserve

Bank of San Francisco. Perrin

and his board agreed to set aside

the No. 1 notes of each

denomination for Adolph Miller.

Library of Congress photo LCN

2016884243.

Figure 5. Adolph Miller was a professor of

economics and finance, not a banker. The

Federal Reserve Act required at least two of

the five appointed members to have banking

or finance experience. The Act directed the

President to ensure the board had

commercial, industrial and geographic

diversity. Library of Congress photo LCN

2016865736.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

340

Miller entered government in 1913 as assistant to the secretary of the Interior, and

Woodrow Wilson appointed him to the Federal Reserve Board in the summer of 1914.

The San Francisco Serial Number 1 Notes

While Miller’s academic career took him across the country, and he ultimately landed in

Washington on the Federal Reserve Board, he kept his fondness for his hometown of San

Francisco. Accordingly, after the Federal Reserve banks opened in mid-November, Miller

contacted Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Chairman John Perrin and inquired whether the

bank would allow him to purchase the serial number 1 notes.

The following letters describe what transpired:

December 4, 1914

Dear Professor Miller,

At a full meeting of the board yesterday it was the unanimous opinion, and so voted, that we

would have great pleasure in granting your request to set apart for your purchase No. 1 of our

Federal Reserve notes of each denomination.

Yours faithfully,

John Perrin

Federal Reserve Agent

December 10, 1914

Dear Mr. Perrin,

I am in receipt of your favor of the 4th inst., advising me that your board had unanimously

voted to set apart for my purchase No. 1 of each denomination of the Federal reserve notes as

they are issued. Will you please convey to the Board my warm appreciation for its kindness.

I enclose herewith my check for $185.00 on the First National Bank of Berkeley, with which you

can in such way as you may deem to be convenient and proper take up these notes as they are

issued for circulation.

Faithfully yours.

A. C. Miller

December 10, 1914

Dear Professor Miller:

The first Federal Reserve notes have today been issued to this bank, $420,000 in fives and

tens. I personally took precaution to have the No. 1 of each denomination put aside to be held for

you until notes of the other denominations have been received.

Respectfully,

John Perrin

Federal Reserve Agent

December 15, 1914:

Dear Professor Miller:

Your letter of the 10th instant containing your check for $185 has been received. Federal

Reserve notes of $5. and $10. denomination have been left in the paying teller’s cash, placed in

a sealed envelope marked with your name and contents. There is no telling just how much delay

there will be in our receiving denominations of $20., $50., and $100. It therefore seems advisable

that I return your check, which is enclosed herewith.

When we get the set complete, I will advise you and you may then send check payable to this

bank.

I have taken occasion to repeat the instructions regarding these to all those responsible for

handling the notes in order there be no slip in complying with your wishes.

Yours faithfully,

John Perrin.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

341

December 21, 1914:

Dear Mr. Perrin:

Your letter of December 15th returning Mr. Miller’s check for $185.00 is at hand. Mr. Miller

is very much pleased to know you have set aside for him notes Nos. 1 of the five and ten dollar

denominations; and upon receipt of word from you that the Notes of twenty, fifty and one hundred

dollar denominations are ready, he will be very glad to send his check as you suggest.

Sincerely yours,

Ray M. Gidney

Private Secretary to Professor Miller

May 24, 1915:

Dear Professor Miller:

Enclosed herewith by registered mail $185.00 in Federal Reserve notes, consisting of note No.

1 of each denomination.

Respectfully,

John Perrin, Chairman of the Board

John Perrin died in 1931 at age 74. Adolph Miller died in 1953 at age 86. Miller’s serial

No. 1 set was meticulously preserved when it reached the numismatic market in 2011.

Ironically, after sending its No. 1 notes to Adolph Miller, the Federal Reserve Bank of San

Francisco’s currency collection still holds a Series of 1914 No. 1 Red Seal. It is the G1A Chicago

$50. I have no idea how that happened.

Figure 6. Red seal FRNs were short-lived. The notes were plagued with serious fading of the red seals

and serial numbers. Treasury Secretary McAdoo approved the change to blue seals and serials

August 9, 1915. The first blue seal notes were delivered to the FRB of Dallas. Heritage Auctions

archives photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

342

Sources

Federal Reserve Act, original document signed by President Woodrow Wilson:

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/federal-reserve-act-966

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco history: https://www.frbsf.org/our-district/about/our-history/ &

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/annual-report-federal-reserve-bank-san-francisco-476/forty-years-federal-

reserve-banking-economic-growth-twelfth-federal-reserve-district-1914-1954-18418

Federal Reserve history: https://www.federalreservehistory.org/time-period/feds-formative-years , and Allan Meltzer,

A History of the Federal Reserve. vol. 1, 1913-1951. Univ Chicago Press, 2003.

Federal Reserve large size notes and their origin: Huntoon/Yakes/Murray/Lofthus, The Series of 1914 and 1918

Federal Reserve Notes, Paper Money, May/June 2012 at https://www.spmc.org/home

Miller, Perrin correspondence: Records of the Federal Reserve System, Board of Governors, Central Subject File

1913-1954, Record Group 82/450/64/35/6 Box 2601, File 610 FRNotes 1914-1915.

Miller biography: https://www.federalreservehistory.org/people

Ralph. Joseph, quote: Bureau of Engraving and Printing Annual Report for Fiscal Year 1914, Oct. 28, 1914, p. 9.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

343

High Serial Discovery

$2 LT Series of 1928C Mule

Small size U.S. variety collector Derek Higgins reeled in the highest reported serial number yet

found on a $2 Legal Tender 1928C mule from eBay in March 2023. His find is C03473448A L180/290,

which extends the known range by over half a million serials. The total reported range is now B97675359A-

C03473448A, a ten percent increase.

A mule is defined as a note with a micro-size plate serial number on one side and a macro on the

other. This 1928C mule variety is characterized by a micro-size plate serial number on the face and a macro

on the back. Such mules resulted from a mix of micro and macro plates on both the back and face presses

during a transition period after the size of the plate serial numbers was increased at the request of the Secret

Service so their agents could read the numbers on worn notes.

The last Series of 1928C face plates were retired February 12, 1940. Consequently, the only macro

backs that could have been mated with them to produce mules had to be printed before then. There were

two such back printings. The first was a temporary early use of macro back plates between August 22 and

September 7, 1939. The second began four and a half months later on January 22, 1940 when the macro

back plates went into sustained regular production.

All the known $2 Series of 1928C mules came from the August 22-September 7, 1939 press run.

In contrast, the macro backs that were printed beginning January 22, 1940 were mated with 1928D faces

later in 1940 owing to the lag time between back and face printings.

The production of the Series of 1928C mules is inseparable from the equally scarce $2 Series of

1928D BA block non-mules. All the macro backs on the 1928D BA block notes were from the same August

22-September 7, 1939 press run. The use of 1928D faces had begun March 13, 1939 so the macro backs

from that run served as the first macro back feed stock for them as well.

The first $2 serial number printed in 1940 was C00872001A so the last of the serials in the BA

block were used on the 1928C mules and the first of the 1928D non-mules in late 1939.

The important early use of the macro backs owes its origin to a sudden temporary surge in $2 back

production between August 11 and September 7, 1939 when about five million backs were ordered.

Maximum production was reached on August 22 when eight of the newly available macro back plates were

added to the presses to augment production from 26 micros.

The Paper

Column

Peter Huntoon

Figure 1. The serial number on this Series of 1928C mule printed in early 1940 extends the

known serial number range for the variety by 10%. Derek Higgins photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

344

A total of 27 different micro back plates were used between August 11 and September 7, one being

phased out before the eight macros were added on August 22. Production from the eight macros accounted

for about 20 percent of the backs printed during this period.

The backs moved forward to face production on or slightly before September 8, and were finished

by December 15. At the time, about 43 percent of face production involved micro Series of 1928C plates,

as a result, many of the macro backs found themselves muled with 1928C faces. These scarce 1928C mules

were the result. Serial numbering of the group commenced at the end of December and ended in January.

The most exciting find yet to be made in the$2 1928 Legal Tender series is a 1928C mule star note.

It is possible no examples were printed; however, there is nothing to preclude it.

Any change in our understanding of the production of scarce varieties such as these 1928C mules

and 1928D BA non-mules is newsworthy. Specimens gradually have leaked into the market over the

decades, most being in low grades. There were no collectors who were even aware of their existence let

alone saving them back when they were current. At present, no true uncirculated examples have been found

of either variety.

Sources of Data

Huntoon, Peter, Sep-Oct 1992, The $2 Legal Tender Series of 1928C and 1928D mules: Paper Money, v. 31, p. 156-161, 169.

Huntoon, Peter, Jan-Feb 1997, $2 legal tender Series of 1928C mules and Series of 1928D BA block non-mules: Paper Money, v.

36, p.7-12.

Huntoon, Peter, May-Jun 2001, Profile of two rarities, $2 legal tender Series of 1928C mule & Series of 1928D BA block non-

mule: Paper Money, v. 40, p. 218-228.

Huntoon, Peter, Jul-Aug 2012, Origin of marco plate numbers laid to Secret Service: Paper Money, v. 51, p. 294, 296, 316.

Huntoon, Peter, Mar-Apr 2023, Legal tender Series of 1928 non-star serial number ranges: Paper Money, v. 62, p. 100-110

Table 1. Reported serial number ranges for the $2 LT Series of 1928 varieties.

Series Treas.-Sec'ry First or Low Delivered Last or High Delivered First or Low Last or High

1928 Tate-Mellon A00000001A Apr 24, 1929 A96520744A 1933 *00000001A *00688584A

1928A Woods-Mellon A51108220A 1930 B08965670A 1934 *00732343A *01055383A

1928B Woods-Mills A86398443A 1933 B09004381A 1934 *00942054A *01053286A

1928C Julian-Morganthau B09008001A Jun 15, 1934 C25426677A 1941 *01062930A *02039694A

1928C mule Julian-Morganthau B97675354A 1939 C03473448A 1940 none reported

1928D mule Julian-Morganthau B86933784A 1939 D08430054A 1944 *01875119A *02619482A

1928D Julian-Morganthau B97269954A 1939 D35923578A 1946 *01972969A *03215773A

1928E Julian-Vinson D29712001A Feb 25, 1946 D39755123A 1947 *03212775A *03227372A

1928F Julian-Snyder D36192001A Sep 25, 1946 D82673798A 1950 *03236520A *03644508A

1928G Clark-Snyder D78552001A Jan 16, 1950 E30760000A May 6, 1953 *03648001A *04152000A

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2023 * Whole No. 347

345

Union Occupation and the Fate of Baugh’s Cotton Mill in Alabama

by Bill Gunther and Charles Derby

In the months leading to the Civil War, most Northerners, including President Abraham Lincoln, believed that

many white Southerners were against secession. On this basis, Lincoln thought that a “conciliatory” approach to any