Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

Benjamin Franklin's Image on U.S. Currency--Rick Melamed

Unissued 1899 Treasury Note--Peter Huntoon

New High $2 Series 1928C Mule Discovery--Peter Huntoon

Money Used in Japanese-American Internment Camps--Steve Feller, et. al.

In God We Trust on U. S. Currency--Peter Huntoon

The Kirtland Safety Society--Douglas Nyholm & Dave Hur

New Fractional Discovery--Rick Melamed

official journal of

The Society of Paper Money Collectors

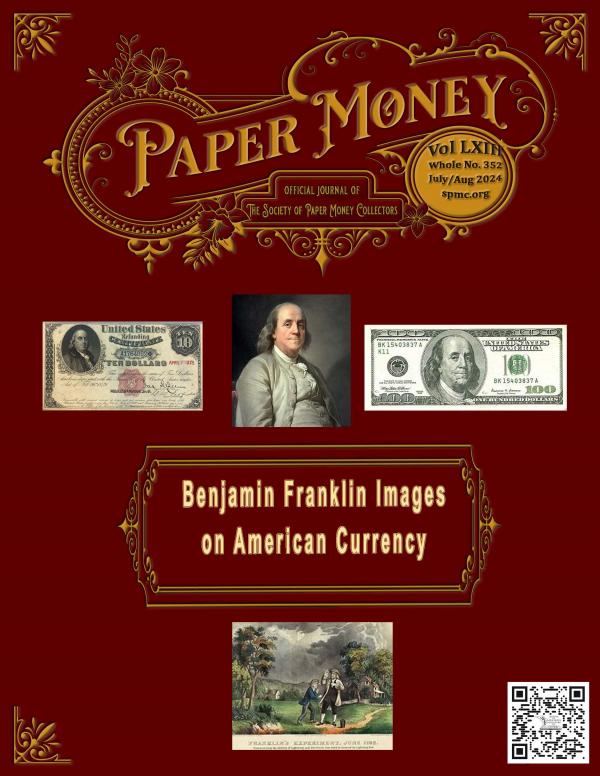

Benjamin Franklin Images

on American Currency

America’s Oldest and Most Accomplished Rare Coin Auctioneer

1550 Scenic Ave., Suite 150, Costa Mesa, CA 92626 • 949.253.0916

470 Park Ave., New York, NY 10022 • 212.582.2580 • NYC@stacksbowers.com

84 State St. (at 22 Merchants Row), Boston, MA 02109 • 617.843.8343 • Boston@StacksBowers.com

1735 Market St. (18th & JFK Blvd.), Philadelphia, PA 19103 • 267.609.1804 • Philly@StacksBowers.com

Info@StacksBowers.com • StacksBowers.com

California • New York • Boston • Philadelphia • New Hampshire • Oklahoma • Virginia

Hong Kong • Paris • Vancouver

SBG PM AugGlobal2024 HLs V2 240701

LEGENDARY COLLECTIONS | LEGENDARY RESULTS | A LEGENDARY AUCTION FIRM

Contact Our Experts for More Information Today!

West Coast: 800.458.4646 • East Coast: 800.566.2580

Info@StacksBowers.com

August Global Showcase Auction Highlights from

STACK’S BOWERS GALLERIES

An Event Auctioneer Partner of the ANA World’s Fair of Money®

Auction: August 12-16 & 19-22, 2024 • Costa Mesa, CA

Expo Lot Viewing: August 4-9, 2024 • Rosemont, IL

Highlights from The Porter Collection

Peter A. Treglia

Director of Currency

PTreglia@StacksBowers.com

Tel: (949) 748-4828

Michael Moczalla

Currency Specialist

MMoczalla@StacksBowers.com

Tel: (949) 503-6244

Fort Benton, Montana Territory. $5 1875.

Fr. 404. The First NB. Charter #2476.

PMG About Uncirculated 53.

Salem, New Jersey. $100 Original.

Fr. 454a. The Salem National Banking Company.

Charter #1326. PMG Choice Very Fine 35 Net.

Guthrie, Territory of Oklahoma.

$10 1882 Brown Back. Fr. 485.

The Capitol NB. Charter #4705.

PMG Choice Very Fine 35. Serial Number 1.

Fr. 151. 1869 $50 Legal Tender Note.

PMG Choice Very Fine 35.

Fr. 203. 1863 $50 Interest Bearing Note.

PMG Very Fine 25.

Highlights from The Eric Agnew Collection of California National Banknotes

Hanford, California. $50 1882 Date Back.

Fr. 563. First NB. Charter #5863.

PMG Very Fine 25.

Monterey, California. $10 1902 Red Seal.

Fr. 613. First NB. Charter #7058.

PMG Very Fine 30. Serial Number 1.

San Francisco, California. $20 1870. Fr. 1152.

First National Gold Bank. Charter #1741.

PMG Choice Fine 15.

Fr. 776. 1918 $2 Federal Reserve Bank Note. Dallas.

PMG Choice Uncirculated 63 EPQ. Serial Number 1.

237 Benjamin Franklin's Image on U.S. Currency--Rick Melamed

247 Unissued Series 1899 Treasury Note--Peter Huntoon

253 New High $2 Series 1928C Mule Discovery--Peter Huntoon

293 Money Used in Japanese-American Internment Camps-Part I--Steve Feller, et. al.

269 In God We Trust on U.S. Currency--Peter Huntoon

279 The Kirtland Safety Society--Douglas Nyholm & Dave Hur

289 New Fractional Currency Discovery--Rick Melamed

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

232

Columns

Advertisers

SPMC Hall of Fame

The SPMC Hall of Fame recognizes and honors those individuals who

have made a lasting contribution to the society over the span of many years.

Charles Affleck

Walter Allan

Mark Anderson

Doug Ball

Hank Bieciuk

Joseph Boling

F.C.C. Boyd

Michael Crabb

Forrest Daniel

Martin Delger

William Donlon

Roger Durand

C. John Ferreri

Milt Friedberg

Robert Friedberg

Len Glazer

Nathan Gold

Nathan Goldstein

James Haxby

John Herzog

Gene Hessler

John Hickman

William Higgins

Ruth Hill

Peter Huntoon

Brent Hughes

Glenn Jackson

Don Kelly

Lyn Knight

Chet Krause

Allen Mincho

Clifford Mishler

Barbara Mueller

Judith Murphy

Dean Oakes

Chuck O'Donnell

Roy Pennell

Albert Pick

Fred Reed

Matt Rothert

John Rowe III

From Your President

Editor Sez

New Members

Uncoupled

Chump Change

Small Notes

Obsolete Corner

Quartermaster

Cherry Pickers Corner

Robert Vandevender 234

Benny Bolin 235

Frank Clark 236

Joe Boling & Fred Schwan 291

Loren Gatch 296

Jamie Yakes 297

Robert Gill 299

Michael McNeil 301

Robert Calderman 303

Stacks Bowers Galleries IFC

Pierre Fricke 232

FCCB 235

Bob Laub 238

Whatnot 246

Lyn Knight 254

Greysheet 268

Bill Litt 268

Fred Bart 283

World Banknote Auctions 288

Paper Money of U.S. 298

PCGS-C 310

PCDA IBC

Heritage Auctions OBC

Fred Schwan

Neil Shafer

Herb& Martha Schingoethe

Austin Sheheen, Jr.

Hugh Shull

Glenn Smedley

Raphael Thian

Daniel Valentine

Louis Van Belkum

George Wait

D.C. Wismer

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

233

Officers & Appointees

ELECTED OFFICERS

PRESIDENT Robert Vandevender II

rvpaperman@aol.com

VICE-PRES/SEC'Y Robert Calderman

gacoins@earthlink.net

TREASURER Robert Moon

robertmoon@aol.com

BOARD OF GOVERNORS

APPOINTEES

PUBLISHER-EDITOR

Benny Bolin smcbb@sbcglobal.net

ADVERTISING MANAGER

Wendell Wolka purduenut@aol.com

Megan Reginnitter mreginnitter@iowafirm.com

LIBRARIAN

Jeff Brueggeman

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

Frank Clark frank_clark@yahoo.com

IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT

Shawn Hewitt

WISMER BOOk PROJECT COORDINATOR

Pierre Fricke

From Your President

Robert Vandevender IIFrom Your President

Shawn Hewitt

Paper Money * July/August 2020

6

jeff@actioncurrency.com

LEGAL COUNSEL

Robert Calderman gacoins@earthlink.com

Matt Drais stockpicker12@aol.com

Mark Drengson markd@step1software.com

Pierre Fricke pierrefricke@buyvingagecurrency.com

Loren Gatch

Shawnn Hewitt

Derek Higgins

lgatch@uco.edu

shawn@north-trek.com

derekhiggins219@gmail.com

Raiden Honaker raidenhonaker8@gmail.com

William Litt billitt@aol.com

Cody Regennitter cody.reginnitter@gmail.com

Andy Timmerman andrew.timmerman@aol.com

Wendell Wolka purduenut@aol.com

For many years, Nancy and I have been fans of Major League Baseball.

While in Florida, we often attended the Miami Marlins games and even had

season tickets one year when they were still the Florida Marlins. Since my

job has relocated us to California for a period of time, we have become fans

of the LA Angels, especially when Shohei Ohtani was playing with them

before his departure for the Dodgers. During our last visit to Angels

Stadium a couple of weeks ago, I overheard someone attempting to buy

refreshments using cash. They were quickly informed that no vendors at

Angels Stadium accept cash anymore and a credit card must be used for any

purchases at the Stadium. More and more, we seem to be moving toward a

cashless society. I suppose there is a lawyer out there somewhere who can

explain to me how they get away with not accepting legal tender as is printed

on our currency. It will be interesting to see how, in the future, it affects the

currency collecting hobby, since a large part of the fun was always searching

for treasures in one’s change from a transaction.

I'm writing this as we prepare to staff our SPMC table once again at the

Long Beach Expo. I am not sure how many of our members will be in

attendance although I did learn that our Vice President, Robert Calderman,

will also be joining me at the show with a retail table of his own.

Our next big event will be the ANA World’s Fair of Money in Chicago.

The SPMC will have a table at that show, and I expect many of our members

to be there with us. We are also planning to participate in the youth treasure

hunt again at this show to help educate the younger generation about our

hobby.

As some of you may know, according to our bylaws, the current Past

President of the SPMC continues to serve on our Executive Board as a

voting member for the length of time they served as President. I am pleased

to announce that Past President, Shawn Hewitt, has been reappointed and

confirmed as a member of our Board of Governors to fulfill the term of Jerry

Fochtman who passed away back in February. This ensures that Shawn will

remain a voting member of our leadership past next June when his existing

term expires. Shawn continues to be a great asset to our organization, and I

look forward to seeing his continued contribution to the SPMC.

I trust everyone is having a nice Summer and I look forward to seeing

many of you at upcoming shows.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

234

Terms and Conditions

The Society of Paper Money Collectors (SPMC) P.O. Box 7055,

Gainesville, GA 30504, publishes PAPER MONEY (USPS 00‐

3162) every other month beginning in January. Periodical

postage is paid at Hanover, PA. Postmaster send address

changes to Secretary Robert Calderman, Box 7055, Gainesville,

GA 30504. ©Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc. 2020. All

rights reserved. Reproduction of any article in whole or part

without written approval is prohibited. Individual copies of this

issue of PAPER MONEY are available from the secretary for $8

postpaid. Send changes of address, inquiries concerning non ‐

delivery and requests for additional copies of this issue to

the secretary.

MANUSCRIPTS

Manuscripts not under consideration elsewhere and

publications for review should be sent to the editor. Accepted

manuscripts will be published as soon as possible, however

publication in a specific issue cannot be guaranteed. Opinions

expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect those of the

SPMC. Manuscripts should be submitted in WORD format via

email (smcbb@sbcglobal.net) or by sending memory stick/disk

to the editor. Scans should be grayscale or color JPEGs at

300 dpi. Color illustrations may be changed to grayscale at the

discretion of the editor. Do not send items of value.

Manuscripts are submitted with copyright release of the author

to the editor for duplication and printing as needed.

ADVERTISING

All advertising on space available basis. Copy/correspondence

should be sent to editor.

All advertising is pay in advance. Ads are on a “good faith”

basis. Terms are “Until Forbid.”

Ads are Run of Press (ROP) unless accepted on a premium

contract basis. Limited premium space/rates available.

To keep rates to a minimum, all advertising must be prepaid

according to the schedule below. In exceptional cases where

special artwork or additional production is required, the

advertiser will be notified and billed accordingly. Rates are

not commissionable; proofs are not supplied. SPMC does not

endorse any company, dealer, or auction house. Advertising

Deadline: Subject to space availability, copy must be received

by the editor no later than the first day of the month

preceding the cover date of the issue (i.e. Feb. 1 for the

March/April issue). Camera‐ready art or electronic ads in pdf

format are required.

ADVERTISING RATES

Editor Sez

Benny Bolin

Required file submission format is composite PDF v1.3

(Acrobat 4.0 compatible). If possible, submitted files should

conform to ISO 15930‐1: 2001 PDF/X‐1a file format standard.

Non‐ standard, application, or native file formats are not

acceptable. Page size: must conform to specified publication

trim size. Page bleed: must extend minimum 1/8” beyond

trim for page head, foot, and front. Safety margin: type and

other non‐bleed content must clear trim by minimum 1/2”.

Advertising c o p y shall be restricted to paper currency, allied

numismatic material, publications, and related accessories.

The SPMC does not guarantee advertisements, but accepts

copy in good faith, reserving the right to reject objectionable

or inappropriate material or edit copy. The SPMC

assumes no financial responsibility for typographical

errors in ads but agrees to reprint that portion of an ad in

which a typographical error occurs.

Benny

Space

Full color covers

1 Time

$1500

3 Times

$2600

6 Times

$4900

B&W covers 500 1400 2500

Full page color 500 1500 3000

Full page B&W 360 1000 1800

Half‐page B&W 180 500 900

Quarter‐page B&W 90 250 450

Eighth‐page B&W 45 125 225

Happy summer to all and to all a cool and fun one. I hope you all

are having a good time that is filled with many new and exciting places,

activities and new purchases. I encourage you all to go to a show or too.

They seem to be back in force and the market is great.

For me--it is a time of waiting and summer farm duties in the midst of

a near diastrous computer failure.

Watching and waiting for the birth of my first grandchild. That is a

occurrence that I hope to be able to report on and show pictures of in

the next issue. Little Olivia Jo is being very mobile and seems to be

developing a sassy, rambunctious attitude in-vitro!

Living on a farm like I have my entire life has its' share of summer

duties when you have a full-time job during August to June. My main

duty is moving the pasture. We have 35 acres and all the rain this year

casued me to get a late start but it hastened the weed growth which

means I have to go slower. Oh well, more time to ponder paper.

I have had computers since the day of the TI-99 4A. I had a big stock

of cassette tapes and player (the main storage device) and could really

make that baby since. Image a RAM of 64K! All to say, they have now

passed me by. I had this issue almost in the books and suddenly, when I

turned it off, it said Microsoft need to update so I gave permission to

update and turn off. Next day pushed the power button--NOTHING! I

tried all the tricks to get it working and nothing worked. I had not

backed up all my info for the past month, so I thougt I was toast.

Imagine my surprise when I took it to Best Buy and they plugged it in

and it was fine. Took it home and NOTHING! Back to BB and it was

still fine. Took it home and plugged it in to my wifes system and woola,

it was fine. All these years of using computers and this was the first

time I found out that a monitor can go bad and disrupt everything.

Whew--it works!

Enough of my rambling and hopefully you will have a great summer.

Till next time! Stay safe and enjoy summer!

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

235

The Society of Paper Money

Collectors was organized in 1961 and

incorporated in 1964 as a non-profit

organization under the laws of the

District of Columbia. It is

affiliated with the ANA. The

Annual Meeting of the SPMC is

held in June at the International

Paper Money Show. Information

about the SPMC, including the

by-laws and activities can be

found at our website--

www.spmc.org. The SPMC does

not does not endorse any dealer,

company or auction house.

MEMBERSHIP—REGULAR and

LIFE. Applicants must be at least 18

years of age and of good moral

character. Members of the ANA or

other recognized numismatic

societies are eligible for membership.

Other applicants should be sponsored

by an SPMC member or provide

suitable references.

MEMBERSHIP—JUNIOR.

Applicants for Junior membership

must be from 12 to 17 years of age

and of good moral character. A parent

or guardian must sign their

application. Junior membership

numbers will be preceded by the letter

“j” which will be removed upon

notification to the secretary that the

member has reached 18 years of age.

Junior members are not eligible to

hold office or vote.

DUES—Annual dues are $39. Dues

for members in Canada and Mexico

are $45. Dues for members in all

other countries are $60. Life

membership—payable in installments

within one year is $800 for U.S.; $900

for Canada and Mexico and $1000

for all other countries. The Society

no longer issues annual membership

cards but paid up members may

request one from the membership

director with an SASE.

Memberships for all members who

joined the Society prior to January

2010 are on a calendar year basis

with renewals due each December.

Memberships for those who joined

since January 2010 are on an annual

basis beginning and ending the

month joined. All renewals are due

before the expiration date, which can

be found on the label of Paper

Money. Renewals may be done via

the Society website www.spmc.org

or by check/money order sent to the

secretary.

WELCOME TO OUR

NEW MEMBERS!

BY FRANK CLARK

SPMC MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

NEW MEMBERS5/05/2024 NEW MEMBERS 6/05/2024

Dues Remittal Process

Send dues directly to

Robert Moon

SPMC Treasurer

104 Chipping Ct

Greenwood, SC 29649

Refer to your mailing label for when

your dues are due.

You may also pay your dues online at

www.spmc.org.

REINSTATEMENTS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

None

15698 Christoff Polagni, Website

15699 Darlene Wright, Website

15700 Robert Nowak, Website

15701 Uilson Boberto Ponce, Website

15702 Brent Enyart, Facebook

15703 Paul Dixon, Frank Clark

15704 Leonard Schulfer, Bank Note Reporter

15705 Robert Spiller, Website

15706 Kevin McCandless, Robert Calderman

15707 Joshua Grim, Website

15708 Paul Antonucci, Website

15709 Jim Haxby, James Haxby

15710 Gayle White, Derek Higgins

15711 Savannah Kelly, Frank Clark

15712 Peter Brouker, Tom Denly

15713 Les Cannaday, Robert Calderman

REINSTATEMENTS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

None

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

236

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN’S IMAGE ON

AMERICAN CURRENCY

by Rick Melamed

One of the most notable founding fathers of the United States

was the legendary Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790). He was an

accomplished writer, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer,

publisher, and more; he was a leading intellectual of the day. In

France, where he spent 10+ years as an ambassador, Franklin was

feted and adored by French nobility (including King Louis XVI and

his wife Marie Antoinette) as he actively campaigned for financial

and military aid to fight the British during the Revolutionary War.

His efforts led to much needed funding and foreign troops that were

critical to America’s victory in the Revolutionary War.

Franklin’s most noteworthy commercial success was the

printing of the Pennsylvania Gazette, which he began publishing in 1729. It was acknowledged as one of the

best colonial newspapers. Franklin had a sharp business acumen. He was one of the first American franchisers.

He would supply various printers throughout the colonies, the equipment, and the expertise to create and

publish newspapers and pamphlets. In return, Franklin would get 1/3rd

of the profits over a 6-year period. In

1732, Franklin first published the Poor Richard’s Almanack (sic). The Almanac contained a

calendar, weather, poems, sayings and astronomical and astrological information. It was very popular, selling up

to 10,000 copies every year. He would continue to publish the almanac for 25 consecutive years, speaking to his

practical values of thrift, hard work, education, community spirit, self-governing institutions, and opposition to

religious and political authoritarianism.

Franklin was also a noteworthy scientist and inventor. He was well versed in physics where he pioneered

the study of electricity. Some of his inventions included the lightening rod, bifocals, swim fins, flexible urinary

catheter, the Franklin stove and more. He founded many civic organizations including the Library Company,

Philadelphia’s first fire department, and the University of Pennsylvania. Franklin also became the first

postmaster General of the U.S. Franklin’s image is widely found on postage stamps, coins, commemoratives

and currency. In this article we will explore the myriad of images of Franklin on American issued currency.

In total we used 28 different images - attesting to our reverence of Franklin. Where we can, we will showcase

images that can be attributed to specific artists and/or engravers.

This portrait of Ben Franklin was painted by Scottish artist, David Martin

in 1767. Martin painted Benjamin Franklin during one of Franklin’s trips to

Europe. It is a wonderful rendering showing a pensive Franklin, deep in

study. The only unusual thing is his hair; it is sporting a wig, something

Franklin rarely wore. This image has been used scores of times on Obsolete

currency, and only once on Federally issued currency. David Martin (1737 –

1797) was born in Fife, Scotland. He studied in Italy and England, before

gaining a reputation as a portrait painter. This portrait resides in the White

House, but there are at least 7 other copies including a 2nd one by Martin that is

at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

237

Shown above are four examples of Martin’s portrait of Franklin. Top Left: $50 1847 Interest Bearing

Treasury note (the only Treasury issued note using the Martin image). Top Right: $100 The President Directors

& Co. Bank of Augusta, GA. remainder note. Bottom Left: $1 remainder Blackstone Canal Bank of

Providence, RI; Bottom right: $20 Towanda Bank, PA. Note how top right image is repositioned, facing right.

Left: During his time as a diplomat in France

(1776–85), Madame Brillon de Jouy

(accomplished French musician and composer)

commissioned Franklin’s portrait. In a letter,

de Jouy praised Franklin for his sound moral

teaching and lively imagination but found his

“droll roguishness” most endearing. The

artist, Joseph Siffred Duplessis (1725 -1802)

was born in Carpentras, near Avignon,

France. He was a well-respected portraitist

who won many prestigious artistic awards.

Duplessis painted this recognizable portrait of

Franklin, found on scores of notes from 19th

century Obsoletes. Painted c.1785, this portrait now

hangs in the Smithsonian National Gallery. Note the collarless jacket and vest. Above Right: This engraving

was created by Charles Burt (1823-1892), a Scottish born American and principal engraver at the U.S. Treasury.

While the Duplessis portrait on the left was painted during Franklin’s lifetime, the Burt engraving, which

borrows heavily from Duplessis, was done well after Franklin’s death. Note how the fur lined coat collar of the

engraving differs from the Duplessis painting, in which Franklin is wearing a collarless jacket and vest.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

238

Shown below are 2 examples of Obsolete notes with the Duplessis portrait with Franklin wearing a

collarless jacket. Below Left: A $5 remainder note from Franklin Bank in Baltimore. Below Right: A $50

remainder note from The Bank of Chambersburg, PA.

The first appearance of the

Charles Burt engraving of Franklin on a

Treasury issued note (with the fur

collar) appears on the Franklin 1874

$50 Legal Tender Note (top left).

Franklin is found on the 1879 $10

Refunding Certificate (bottom left).

Franklin also appears on the 1893

American Bank Note Columbian

Exhibition ticket (top right). It is

interesting to see Franklin facing to

the left; usually Burt images have

Franklin facing right.

Shown below are Charles Burt engraved portraits on 4 different small sized $100 notes: 1928 green

seal Federal Reserve Note; 1929 brown seal Federal Reserve Bank Note; 1928 gold seal Gold Certificate;

and 1966 red seal U.S. Note.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

239

Banknote designer Brian Thompson of the

BEP created this portrait of Ben Franklin for the

modern $100 note. Thompson, who also designed

the modern $20 note, took 17 years to create the

design. Borrowing from the Duplessis portrait,

Thompson elevates this portrait, as Franklin’s

piercing gaze makes him come alive.

Below: Franklin and Electricity, found on the 1882 $10 National

Bank Note, was engraved by Alfred Jones and James Simillie for the

American Bank Note Co. Jones (1819-1900) was a noted British

artist who illustrated many notable books, was published in art

magazines, and was associated with the Carlton Studio, one of the largest commercial art studios in

London at the turn of the 20th century. James David Smillie (1833 –1909) was a noted American artist,

cofounder of the American Watercolor Society and New York Etching Club. The image of Franklin

holding a kite string with a key during a lightning storm is representative of one of Franklin’s great

achievements, discovering electricity.

Left: This engraving of Franklin flying a

kite with a young boy is considerably

different than the rendition used in the

production of the 1882 National Bank

Note. This rare, likely unique, 1863

proof of Franklin and Electricity was

never used in production While not

definitive, we assume Alfred Jones and

James Simillie were the engravers.

Interesting to point out that the bronzing

and 3 pie shape cancellations are similar

to what was used in Fractional Currency

Experimentals.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

240

To the left is a dour

engraving of a young, trim

and upright Franklin

working at a desk setting

type at his chosen

profession as a printer.

Top Left: 1860’s $5

remainder note from the

Franklin Bank of

Greenville, Illinois. Bottom

Left: Franklin is found on

an 1860’s $20 remainder

note from The Bank of

North Carolina in Raleigh.

Both are engraved by an unknown artist for

the American Bank Note Company.

Above Left: An enchanting image of a young boy resting against a sitting Ben Franklin who is

genuflecting to the bust of George Washington. The painting is entitled Franklin, Child & Washington by

noted American artist, Francis W. Edmonds (1806-63). It was engraved by Alfred Jones (1819-1906). Top

Right: 1860’s $2 remainder from the Bank of Amsterdam, NY. Bottom Right: 1860 $10 remainder note

from the Citizens’ Bank of Louisiana at Shreveport.

This $10 Franklin

Silk Company note

depicts a well-dressed

Franklin with a far-off

gaze holding a pen and

writing tablet while

sitting at a desk. Bolts

of lightning are seen to

his right.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

241

Philadelphia printers, C. Toppan & Co., created this engraving of a Franklin bust on a $5 Franklin

Bank of Baltimore remainder note. The marble bust was created by Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1821), a

French neoclassical sculptor. Born at the Place of Versailles, Houdon is famous for his portrait busts and

statues of philosophers, inventors and political figures. The archives of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

in New York offers a very good character description of Ben Franklin: “Houdon captures those aspects of

Franklin's somewhat sly persona, which so fascinated French society during his nine years in Paris

(1776–85) representing the newly independent United States. His natural unpowdered hair, simple Quaker

suits, and benign wit all stood in sharp contrast to the norms of diplomatic circles in which Franklin

moved. Franklin's celebrity attracted fashionable hostesses and crowds in the street alike and his image

was widely disseminated by the leading artists of the time.”

Above is a pair of portraits on $20 Franklin Bank notes (Jersey City note from 1827 and Boston

note from 1836) with Franklin holding his spectacles. The artist and printer are unknown. One portrait

Franklin is holding his spectacles in his left hand and the other portrait they are in his right hand.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

242

Above is an undated merchant note from Franklin Mining Company in Michigan. Engraved and

printed by the American Banknote Co. This is a wonderful deptiction of Franklin at his desk.

FRANKLIN PROFILES

Top Left: 1914 red seal Federal Reserve note engraved by Marcus Baldwin (1853-1925) during his

tenure as a BEP engraver. Baldwin also had stints at the American and National Banknote Cos. Top

Right: A pair of Franklin profiles face each other on this 50¢ remainder note from the Franklin Institute of

Philadelphia (same image used on U.S. stamps). Bottom Left: Franklin and Washington facing each other

on a $100 Union Bank remainder note from Philadelphia.

Bottom Right: Rudimentary profile of Franklin on an 1819 $100 Obsolete from the Franklin Bank of

Baltimore, MD.

A 1¢ and 30¢ encased postage depicts

a right and left facing Franklin. Since

encased postage was used as circulating

money just before being replaced by

Fractional currency in 1862, they merit

inclusion in this article.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

243

Crude Franklin profile from an

early Post note with no amount filled

in. From the Franklin Bank of New

York City. The bank was in existence

from 1818-1830.

Undated $10 proof from

Franklin Bank of Baltimore. It’s

quite an interesting Franklin profile

wearing a cap.

$5 note from the State Bank

of Trenton, NJ dated May 10,

1822

MISCELLANEOUS FRANKLIN IMAGES

The following Franklin engraved images are of a lesser quality. They are found on merchant notes

and College currency where artistic expertise was not so precise.

Top Left: 1883 50¢ merchant note from the Walker Iron and Coal Company from Rising Fawn, GA.

Top Right: 187x $500 college currency note from the Indianapolis Business College.

Bottom Left: (ca. 1868-70) Van Allen's Quarter-Dime Soap $1 "Family Lease" Advertising Note.

The reverse has a recipe to make 60 lbs. of soap. Bottom Right: Undated 50¢ merchant note to Franklin

Coffee House in New York City.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

244

Above is another rather rudimentary image of Franklin on a $1,000 college currency note from

Baylies Mercantile College of Keokuk, Iowa.

Franklin’s contribution to Continental Currency is also notable.

It is estimated that he printed over 2,500,000 notes for the

Colonies. His innovations included the development of the

multicolored pattern on currency. He is supposedly behind the use

of embedding mica and nature prints on Continental notes as well.

Shown to the right is an example of a Franklin printed note.

There are likely other Ben Franklin images that have been

missed – but the above is comprehensive. Thanks to Wendell Wolka

and Dustin Johnston of Heritage for their input. Also, to

Stack’s/Bowers and Heritage for most of the images contained in this article. Thanks to Katrina London,

Manager of Collections and Curatorial Projects at Kykuit – Home of John D. Rockefeller. Finally, thanks

to my son, Dr. David Melamed, for his excellent editing of this article.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

245

Shop Live 24/7

Scan for $10 off your first purchase

whatnot.com

Unissued Series of 1899

Treasury Notes

Objectives

This article has two objectives: to explain how the unissued Series of 1899 Treasury notes came

about and to pinpoint when the Treasury Department began to move toward ado[ting common designs for

the different classes of U.S. currency. The first attempt to standardize designs involved the unissued Series

of 1899 Treasury notes.

This situation merges the collecting of some large size notes with four fascinating souvenir cards

that round out the story. Too many large-size type collectors turn up their noses at souvenir cards, a tendency

that I feel robs them of probing some interesting history.

Surprise Discovery of Plate Proofs for $1 Backs

This tale began to unfold for me years ago as we were sorting the BEP proofs that were turned over

to the National Numismatic Collection in the Smithsonian Institution. One day I came upon eight 4-subject

$1 proofs for the backs of the Series of 1899 that looked odd. Sure enough, they bore the header Treasury

note instead of silver certificate. That was totally unexpected and clearly an unissued design.

The Paper

Column

Peter Huntoon

Figure 1. Unissued Series of 1899 $1 Treasury note, a Series of 1899 silver certificate look-a-like, that was

developed to replace the existing Series of 1891 Treasury notes in order that all the current $1s would have

uniformity so they could be handled easily.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

247

The plate proofs carried certification dates from August 5 through September 23, 1899. We never

found 1899 Treasury note backs for other denominations or any faces at all. All of this was strange.

Souvenir Cards

I vaguely recalled something about this unissued series going by so in due course I looked in

Hessler’s 1979 Essay-Proof-Specimen book and found that he illustrated proofs for both faces and backs

of $1 and $2 1899 Treasury notes, but without any information about them (Hessler, 1979, p. 134-135).

Another recollection was that some BEP souvenir cards illustrating unissued Treasury notes also

had gone by so I probably had them. With a little digging I found a great series of four cards from 2002

labeled “United States currency redeemable in coin” (BEP, 2002a,b,c,d). They were Series of 1899 and

their images are illustrated here.

The information that accompanied the souvenir cards explained why we didn’t find production

plate proofs for any other than the $1 backs. The master die for the $1 back was the only one of the four

that had been hardened so it was the only one from which they could make a roll to transfer the image to

plates.

The information accompanying the cards revealed the following about the four master dies.

$1 back begun January 1899/

$1 face began March 1899, work ceased on it during September.

$2 back begun September 1899, finished November, never hardened.

$2 face begun September 1899, finished October, never hardened.

The process that was used in 1899 to create the four Treasury note dies was that they started with

transfer rolls made from the hardened master dies for the Series of 1899 silver certificates. The images from

each were laid into its own new master. A team of engravers then altered the images on the new masters to

Figure 2. The only current $1 and $2 notes in 1899 were silver certificates and Treasury notes. Consequently,

in order to move toward uniformity, they were a logical place to start.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

248

the desired Treasury note forms before the new dies were hardened.

None of the eight $1 back plates that were made were sent to press. However, the existence of the

proofs lifted from them reveals that the master was hardened, a role was made from it; and the eight

production plates were laid-in from the roll.

So how could the BEP employees in 1990 make printing plates to print the souvenir cards if three

of the four masters hadn’t been hardened? Fabrication of a roll requires that the source die be hard.

What they did was use modern electrolytic plate-making technology to create 1-subject printing

plates from each of the masters. Specifically, they fabricated a flat electrolytic alto from each of the masters

by electroplating nickel onto their surfaces. Then they separated the altos from the masters, which carried

a mirror image of the engravings that would serve as molds. They then electroplated nickel onto the altos,

separated the resulting flat forms from them and presto they had perfect replicas of the masters. The replicas

served as the printing plates for the souvenir cards. Notice that this process works regardless of whether the

master dies were hardened or not. You can see that the Bureau employees go to considerable effort to create

the souvenir cards.

Origin and Dilemma of Treasury Notes

Now we get to the heart of the matter. What are these Series of 1899 Treasury notes about and why

weren’t any issued?

U.S. Treasury notes probably are the most interesting and enigmatic of the paper money issues of

the United States. Let’s take a brief look.

Collectors of large size notes know the Treasury notes as the Series of 1890 and 1891. Those notes

were fathered by one of the most contentious political issues of the last half of the 19th century, the debate

over whether unlimited quantities of silver should be monetized.

The debate pitted populists in both parties against the hard money factions in their midst. The

populist movement was particularly strong in the west and south where adherents favored the unlimited

monetization of silver in order to inflate the money supply. By making money plentiful, they believed it

would break what they perceived as a stranglehold that Eastern bankers had on the nation’s gold coin supply.

The perception was that by controlling the gold supply, the bankers maintained high interest rates that stifled

economic growth in the rural areas of the country, Of course, the hard money faction preferred to tie the

money supply to what they perceived was a limited quantity of gold.

The populists gravitated to the Democratic party and the hard money faction to the Republican

party. The populist movement had gained sufficient strength by 1890 that they won passage of the Sherman

Silver Purchase Act of July 14, 1890. The act was an ill-conceived compromise piece of legislation that

required the Treasury to purchase up to 4.5 million ounces of silver per month and coin it. The act was

passed without the support of then Republican President Benjamin Harrison.

Figure 3. Details illustrating the differences between the Treasury note and silver certificate backs.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

249

It resulted in an uncontrolled drain on the

Treasury’s stock of gold. Here is what happened.

The act contained a serious flaw that was

included to demonstrate the commitment of the

United States to a bimetallic monetary standard that at

the time was a 16:1 gold/silver ratio based on $20.67

per ounce gold and $1.2929 per ounce silver. It

stipulated that the Treasury pay for the silver with

Treasury notes, but allowed those notes to be

redeemed in gold or silver coin.

Furthermore, to maintain the now inflated

money supply, the act required that when redeemed

for coin, the Treasury notes had to be reissued in order

that their outstanding circulation equaled the cost of

the silver bullion and silver dollars held by the

Treasury that they had purchased.

Unfortunately, the price of silver steadily

dropped as a result of huge production of silver from

the Comstock Lode in Nevada and mines elsewhere in

the west.

The dilemma the Treasury faced was that

speculators were engaged in a merry-go-round of

buying silver on the metals market where the price of

silver was decreasing, selling it to the Treasury,

receiving Treasury notes, redeeming the notes for gold

coin, selling the gold coin for ever increasing

quantities of silver in the market, pocketing the

difference and repeating the cycle. Most of the gold

was exported whereas net silver imports increased

during 1890 through 1893 (Carlisle, 1894).

In due course, the Treasury had to dip into its $100,000,000 gold reserve fund established by the

Act of July 12, 1882 to feed this frenzy. The Treasury had to sell gold bonds, mostly overseas, to restock

the fund, only to repeat that cycle as well. This quickly ran up the national debt, which itself was payable

in gold. The situation was unsustainable.

Democratic President Grover Cleveland, upon taking office in 1893 at the beginning of his second

detached term, inherited the mess along with the blossoming of the Panic of 1893 and economic depression

that ensued. He perceived the act to be a primary cause of the panic because it eroded public confidence in

the money supply. Therefore, he gave utmost priority to its repeal. He succeeded in getting the silver

purchase provision repealed on November 1,1893. However, repeal of the reissue provision governing the

Treasury notes had to await passage of the Gold Standard Act of March 14, 1900 seven years later during

Republican President McKinley’s term.

William McKinley took office March 4, 1897 and served until his assassination in 1901, which

occurred during the first year of his second term. He was a moderate on the silver/gold issue but leaned

toward the hard money position although in economics his passion was for tariff protection to insulate

American industry. As the campaign unfolded against silverite Williams Jennings Bryan, McKinley’s tariff

platform resonated well in the populous east so he downplayed the silver debate, thus winning a razor thin

victory.

His term was notable for victory in the Spanish–American War of 1898 that brought Puerto Rico,

Cuba, Guam and the Philippines in as colonial possessions as well as the annexation of Hawaii. Ironically,

McKinley argued against American Imperialism; instead, favoring isolationism.

Figure 4. A major priority for Democratic President

Grover Cleveland was repeal of the Sherman Silver

Purchase Act. He managed to win repeal of the

purchase requirement in 1893 but not the

dangerous Treasury note reissue provision.

Wikipedia photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

250

By rejecting the inflationary monetary

policy of free silver, keeping the nation on the gold

standard; and raising protective tariffs, his term saw

the nation recover from the lasting depression that

gripped the nation following the Panic of 1893. Much

credit for this success goes to Lymen J. Gage, an

accomplished banker and staunch Gold Democrat,

whom McKinley appointed as his Secretary of the

Treasury. Gage, formerly president of The First

National Bank of Chicago, served as Secretary from

McKinley’s inauguration until January 31, 1902

during Theodore Roosevelt’s administration. A

priority for Gage and the Republicans in Congress

was to place the nation on the Gold Standard.

However, more immediate at the outset of

McKinley’s term was the lingering problem of the

reissue provision for the Treasury notes. Secretary

Gage also was saddled with the fiasco attending the

failure of the Series of 1896 Educational silver

certificates inherited from John Carlisle,

Cleveland’s second Secretary of the Treasury

The Educational notes had foundered over

a design flaw; specifically, the lack of readily

visible counters on the corners of their faces. That

made sorting the notes difficult and had drawn

howls from the banking and merchant

communities.

At the time Gage took office, the engravers

at the BEP were preparing revised master dies for

the series. Gage had little patience with the series

so he cut the Treasury’s loses by killing the series

on May 3, 1897 (BEP, 1990) and ordering a new

series of $1, $2 and $5 to replace it. Bringing the

replacement Series of 1899 silver certificates to

fruition took two years, thus yielding that series

date for them.

Gage’s authority to do so resided in the

legislation that authorized currency. Those acts

specified the denominations but vested the

Secretary of the Treasury with responsibility for

their designs. The latter included not only the

engravings but also the series designations. The

Secretary could change either at will.

Figure 5. A priority for Congressional Republicans

during William McKinley presidency was passage of

the Gold Standard Act, which occurred in 1900. It

contained a provision that did away with the

lingering Treasury note reissue provision in the

Sherman Silver Purchase Act, thus ending the

issuance of Treasury notes. Wikipedia photo.

Figure 6. Republican McKinley’s Secretary of the

Treasury Lymen J. Gage, a Gold Democrat, authorized

the Series of 1899 $1 and $2 Treasury notes as a first

step in adopting uniform currency designs for the

various classes of currency. His major role was his

service as the administration’s point man for passage

of the Gold Standard Act key, which ironically did

away with Treasury notes. Wikipedia photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

251

Adoption of Uniform Designs

Historically it was a bit peculiar that there were so many different classes of Congressionally

authorized currency and that each class had entirely different designs. Handlers simply had to get used to

sorting them. Apparently, Gage already was sensitive to the sorting issue as a former banker. Now he had

just come away from the Series of 1896 silver certificates debacle over a similar sorting issue.

There were only two class of current $1s and $2s going into the late 1890s; specifically, silver

certificates and Treasury notes. An obvious first step toward uniformity would be to simultaneously replace

the $1 and $2 Series of 1891 Treasury notes with Series of 1899 silver certificate look-a-likes. Consequently,

Gage seized on the opportunity and authorized the replacement of the Series of 1891 Treasury notes with a

Series of 1899 Treasury notes.

1899 Treasury Notes Not Needed

Gage worked with Congress on passage of the Gold Standard Act, which was signed into law by

McKinley on March 14, 1900. Gage’s Treasury people certainly provided language for that act so its terms

were known to them well before it passed.

A provision was included in the Gold Standard Act to solve the Treasury note reissue dilemma.

Section 5 required the Treasury to redeem the Treasury notes and reissue them as silver certificates. The

silver certificates were redeemable only in silver. Thus, the Treasury’s gold would be shielded.

Gage’s Treasury knew that Section 5 was coming and that it would terminate the issuance of

Treasury notes. Being secure that the Gold Standard Act would pass, Gage had the BEP terminate work on

his Series of 1899 Treasury notes as unnecessary during the fall of 1899. That call was correct because

passage of the Gold Standard Act saw to it that Treasury notes ceased to be current thereafter.

Paving the Way

Even though the Series of 1899 Treasury notes never came into being, the idea of using uniform

designs for given denominations was now seeded in the Treasury Department and rattled around for the rest

of the large-note era. The administration of Treasury Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon, who served

from May 1921 through January 1929, took another swipe at implementation in the form of the look-a-like

low denomination Series of 1923 silver certificates and legal tender notes. However, Mellon’s Treasury

prioritized reducing the size of the currency so adopting uniform designs for the larger denomination large-

size notes was shunted aside as unnecessary and wasteful. Uniformity awaited adoption of the small-size

notes beginning at the end of Mellon’s tenure in 1928.

Heck of a story to pull together between collecting some Series of 1890 and 1891 Treasury notes,

the four Series of 1899 Treasury note souvenir cards, and some Series of 1899 silver certificates, eh?

If you want the full story of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act and the Treasury notes of 1890 and

1891, read Huntoon (2022). You can get the article via the Society of Paper Money Collectors website.

Sources

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 1863-1928, Certified proofs lifted from large-size U.S. currency printing plates: National

Numismatic Collection, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 1990, Series of 1897 $5 silver certificate unfinished master face die souvenir card: 1890’s an

American Renaissance series, FUN 1990, Tampa, FL

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 2002a, Souvenir card, Series 1899 Treasury note $1 face, Florida United Numismatists, Orland,

FL, January 2002.

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 2002b, Souvenir card, Series 1899 Treasury note $1 back, Texas Numismatic Association, Fort

Worth, TX, May 2002.

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 2002c, Souvenir card, Series 1899 Treasury note $2 face, American Numismatic Association,

New York, NY, July-August 2002.

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 2002d, Souvenir card, Series 1899 Treasury note $2 back: Long Beach Coin & Collectables

Show, Long Beach, CA, September 2002.

Carlisle, John G., 1894, Gold and silver in the Treasury of the United States, and circulation of silver & silver certificates (chart

with month-end totals including insets for imports and exports of gold and silver, June 1878 through May 1894); in, Annual

Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the state of the finances: Government Printing Office, 992 p.

Hesler, Gene, 1979, U.S. essay, proof and specimen notes: BNR Press, Port Clinton, OH, `262 p.

Huntoon, Peter, May-Jun, 2022, The origin and demise of the Treasury notes of 1890 & 1891: Paper Money, v. 61, p. 86-106.

United States Statutes, July 12, 1882,An Act to enable national banking associations to extend their corporate existence, and for

other purposes: Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

252

United States Statutes, July 14, 1890, Sherman Silver Purchase Act: An Act directing the purchase of silver bullion and the issue

of Treasury notes thereon, and for other purposes: Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

United States Statutes, November 1, 1893, An Act to repeal a part of an act approved July fourteenth, eighteen hundred and ninety,

entitled “An act directing the purchase of silver bullion and the issue of notes thereon, and for other purposes”:

Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

United States Statutes, March 14, 1900, Gold Standard Act; An Act to define and fix the standard of value, to maintain the parity

of all forms of money issued or coined by the United States, to refund the public debt, and for other purposes:

Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

New High $2 Series of 1928C Mule Serial Number Discovery

Peter Huntoon

Small size U.S. variety collectors Derek Higgins and Larry Thomas compete with each other to

find $2 Series of 1928 notes that extend the reported serial number ranges for all the varieties in that popular

series.

Derek, within the last year, has outdone himself by extending the range for the very scarce 1928C

mule variety by buying or spotting three successive highs; specifically, C03473448A, C03716665A and

now C04103686A over the previous high of C02892104A reported back in 2020. He found the latest—

C04102686A J176/289—on the ExecutiveCoin.com website in February 2024.

Larry brought in a new low 1928A Woods-Mellon, new high 1928C Julian-Morgenthau star, and

new high 1928E Julian-Vinson during the same period.

These two have contributed more on the $2 1928 notes in the last couple of years than has come in

during the previous three decades. Send your reports to peterhuntoon@outlook.com

The serial number on this Series of 1928C mule printed in early 1940 is now

the highest reported for this scarce e variety. Executive Coin Co. photo.

Table 1. Reported serial number ranges for the $2 LT Series of 1928 varieties.

Series Treas.-Sec'ry First or Low Delivered Last or High Delivered First or Low Last or High

1928 Tate-Mellon A00000001A Apr 24, 1929 A96520744A 1933 *00000001A *00688584A

1928A Woods-Mellon A50969839A 1930 B08965670A 1934 *00732343A *01055383A

1928B Woods-Mills A86398443A 1933 B09004381A 1934 *00942054A *01053286A

1928C Julian-Morganthau B09008001A Jun 15, 1934 C25426677A 1941 *01062930A *02049788A

1928C mule Julian-Morganthau B97675354A 1939 C04103686A 1940 none reported

1928D mule Julian-Morganthau B86933784A 1939 D08430054A 1944 *01875119A *02619482A

1928D Julian-Morganthau B97269954A 1939 D35923578A 1946 *01972969A *03215773A

1928E Julian-Vinson D29712001A Feb 25, 1946 D40156288A 1947 *03212775A *03227372A

1928F Julian-Snyder D36192001A Sep 25, 1946 D82673798A 1950 *03236520A *03644508A

1928G Clark-Snyder D78552001A Jan 16, 1950 E30760000A May 6, 1953 *03648001A *04152000A

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

253

Lyn Knight Currency Auct ions

If you are buying notes...

You’ll find a spectacular selection of rare and unusual currency offered for

sale in each and every auction presented by Lyn Knight Currency

Auctions. Our auctions are conducted throughout the year on a quarterly

basis and each auction is supported by a beautiful “grand format” catalog,

featuring lavish descriptions and high quality photography of the lots.

Annual Catalog Subscription (4 catalogs) $50

Call today to order your subscription!

800-243-5211

If you are selling notes...

Lyn Knight Currency Auctions has handled virtually every great United

States currency rarity. We can sell all of your notes! Colonial Currency...

Obsolete Currency... Fractional Currency... Encased Postage... Confederate

Currency... United States Large and Small Size Currency... National Bank

Notes... Error Notes... Military Payment Certificates (MPC)... as well as

Canadian Bank Notes and scarce Foreign Bank Notes. We offer:

Great Commission Rates

Cash Advances

Expert Cataloging

Beautiful Catalogs

Call or send your notes today!

If your collection warrants, we will be happy to travel to your

location and review your notes.

800-243-5211

Mail notes to:

Lyn Knight Currency Auctions

P.O. Box 7364, Overland Park, KS 66207-0364

We strongly recommend that you send your material via USPS Registered Mail insured for its

full value. Prior to mailing material, please make a complete listing, including photocopies of

the note(s), for your records. We will acknowledge receipt of your material upon its arrival.

If you have a question about currency, call Lyn Knight.

He looks forward to assisting you.

800-243-5211 - 913-338-3779 - Fax 913-338-4754

Email: lyn@lynknight.com - support@lynknight.c om

Whether you’re buying or selling, visit our website: www.lynknight.com

Fr. 379a $1,000 1890 T.N.

Grand Watermelon

Sold for

$1,092,500

Fr. 183c $500 1863 L.T.

Sold for

$621,000

Fr. 328 $50 1880 S.C.

Sold for

$287,500

Lyn Knight

Currency Auctions

Deal with the

Leading Auction

Company in United

States Currency

Money Used in the Japanese-American Internment Camps of World War II

By Katherine Ameku1, Momo McCloskey Feller2, Ray Feller2,3, and Steve Feller1

Part I (Part II and references in Sep/Oct Issue)

Why the Camps Came to Be

Anti-Japanese racism existed in the United States from the start of Japanese immigration in the late 1800s.

Japanese immigrants were not allowed to become citizens, although their children were protected by the 14th

Amendment and were born as US citizens (Kashima, 2003). However, even these US citizens--over 100,000 Japanese

Americans--were subject to imprisonment in Japanese American camps during World War II.

The Empire of Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on December 7, 1941. War was declared the next day.

Only two months later, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued the now-infamous Executive

Order 9066 (US National Archives, see Figure 1). This required the forced evacuation of anyone of Japanese

ancestry--including United States citizens-- from a “Western exclusion zone.” Figure 2 shows the military order

that put the relocation into action based on Executive Order 9066. Men, women, children, and the elderly were sent

first to short-term “assembly centers” (located in temporary settings like fairgrounds and racetracks) and then to

relocation camps in the interior (read: middle of nowhere) of the United States. Those people who had aroused more

specific suspicion were sometimes placed in a third type of camp, run by the Justice Department or US Army

(US National Park Service).

1Coe College, Cedar Rapids, IA. 2 Jamaica Plain, MA. 3 MIT, Cambridge, MA

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

255

Figure 1: President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 (National Archives).

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

256

Figure 2: Instructions for implementing Executive Order 9066 (National Archives).

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

257

Figure 3: Map of Japanese-American centers of internment during World War II (image from the National Park Service)

Numismatic Items from the Camps

Little has been written on the numismatic remainders of the assembly centers or from the ten relocation centers

established inland for the evacuees. The present research has uncovered numerous numismatic items from these

camps. We have utilized camp newspapers, memoirs, yearbooks from camp high schools, scrapbooks, film footage,

and official reports. We have also had the opportunity to visit some of the camp sites in person. From these sources,

we have begun to piece together the numismatic story of the Japanese American internment camps.

The internees were able to use US paper currency and coins. They also had bank accounts both back home and

in the camps. There were also other forms of money and other related ephemera in assembly centers and relocation

camps. These included paper scrip, event tickets, clothing and other commodity coupons, tokens, lottery tickets, and

co-op receipts.

Coupon Books

Within weeks of camps opening, numismatic items were being mentioned in the camp newspapers. The most

common were coupon books. Shown below is a newspaper from the Santa Anita (CA) Assembly Center with

headlines about coupon books. Many newspapers in the camps had similar reports. These references make clear that

the coupon books were an essential part of the camp economy. A coupon book is shown from the WCCA with one

attached coupon. To redeem coupons for goods, prisoners would have to present the coupon booklet with the coupon

attached. Goods were not exchanged if the coupon was loose. This prevented bartering for goods in the camps and is

the same model as many POW camps in the United States (see Seeley and Frank, 2019).

Although the references to coupon books are frequent, surviving examples are quite limited. This is likely

because the internees were encouraged to use their coupons before leaving. As one article from the Fresno Grapevine

reported on June 6, 1942: “‘Coupon books are not re-imburseable [sic] in cash at the time evacuees are transferred to

other relocation center [sic],’ states E.P. Pulliam. He also suggests that everyone expend their coupon books at the

center store since the same are not negotiable at the War Relocation Centers.” (See Figure 5) Given that the inmates

had to purchase coupon books in Fresno, likely the incentive was even higher to use them up.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

258

Figure 4: The Santa Anita Pacemaker of July 4, 1942.

The play on words indicates the racetrack origin of this assembly center (Densho).

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

259

Figure 5: Fresno Grapevine, June 6, 1942, encouraging internees to use their coupons (Densho).

Figure 6: Coupons being issued at a Japanese Assembly Center (Densho).

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

260

Figure 7: WCCA Center Store chit from a booklet. It was issued in the name of K. Takemoto (Densho).

Cooperatives

Associated Cooperatives of Oakland offered to help the relocation centers in establishing cooperatives. All but

one accepted and established a co-op system (Thompson, 2011). These allowed the prisoners to have more control

over their internal economy and what products were coming into the camps. The co-ops were not limited to stores.

They also included soda fountains, beauty salons, barber shops, shoe repair, photography studios, movie showings a

flower shop, check cashing, and other services (Unrau, 1996). They also produced their own newspapers to keep their

members up to date. The co-ops were very successful--in fact, a year after it opened, the Manzanar co-op was the

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

261

second largest consumer co-op in the country (Thompson, 2011). Patrons had to use the same ration books as those

outside the camps, and examples of ration books issued to internees can be found.

Additionally, there are examples of special coupons for the Co-ops, as well as an incentivized receipt system.

Upon arrival at the camp, many internees did not have much more than what was on their back so the need for supplies

was prevalent. Co-op members paid dues that would go to the purchase of the wares at the co-op stores. When Co-

op members purchased supplies at these stores, they received a dividend. These were profit refunds based on the

sales as evidenced by the issued (and saved) receipts (see Figures 11 & 12).

Although Co-ops were introduced by the WRA, they were run by several committees composed of fellow

prisoners who were elected by cooperative members. These places of business accounted for millions of dollars in

sales. For example, the Tule Lake Cooperator issue from October 30, 1943, reported that the previous three months’

total sales and services amounted to $371,351.02.

Figure 8: Co-op voucher from the Jerome Co-op, 1944 (World War II Japanese American Internment Museum, McGehee, AR)

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

262

Figure 9: Rohwer Camp usage of Co-op coupons (World War II Japanese American Internment Museum, McGehee, AR)

.

Co-op documents and vouchers:

Figure 10: Possibly a membership card for the Manzanar Co-op (image from Densho)

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

263

Figure 11: Patronage receipt from the Manzanar Relocation Camp Co-op (image from the Manzanar National Historic Site)`

Figure 12: Patronage refund receipt from the Manzanar Co-op (image from Densho)

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

264

Figure 13: Canteen in Manzanar; image by Ansel Adams (image from Densho)

Figure 14: Inside an Arkansas Japanese-American Internment Camp Store

(World War II Japanese American Internment Museum, McGehee, AR)

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

265

Figure 15: Outside an Arkansas Japanese-American Camp canteen

(World War II Japanese American Internment Museum, McGehee, AR)

Other Numismatic Items

Other examples of numismatic items in the camps include tickets for recreational activities, such as baseball

tickets, movie tickets, and tickets to events like a birthday ball. Examples are shown below.

Figure 16: Movie ticket for use at Minidoka War Relocation Camp (Steve Feller Collection).

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

266

Figure 17: Poston Movie Ticket (Image from a scrapbook, courtesy of Densho)

Figure 18: Ticket to a Birthday Ball in Jerome (World War II Japanese American Internment Museum, McGehee, AR)

Figure 19: Ticket to baseball games between the US Army at Camp Shelby (Mississippi)

and Japanese American internees from Jerome, AR. The Jerome team won 2 out of 3 games

played in 1943. (California State University, Dominguez Hills, Archives and Special Collections).

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

267

Figure 20: Raffle ticket for Poston III Camp (Image from Densho)

SPMC.org * Paper Money * July/Aug 2024 * Whole No. 352

268

In God We Trust

on U.S. Currency

AN ACT To provide that all United States currency shall bear the inscription

“In God We Trust”

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress

assembled, That at such time as new dies for the printing of currency are adopted in connection with

the current program of the Treasury Department to increase the capacity of presses utilized by the

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the dies shall bear, at such place or places thereon as the Secretary

of the Treasury may determine to be appropriate, the inscription "In God We Trust", and thereafter

this inscription shall appear on all United States currency and coins.

Approved July 11, 1955,

Subsequently, “In God We Trust” was established as the national motto by a Joint Resolution of

Congress signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on July 30, 1956.

Release to the public of $1 silver certificates with the motto on their backs took place on

The Paper

Column

Peter Huntoon

Figure 1. The first small size notes to utilize the national motto were $1

Series of 1957 silver certificates printed on new high-speed 32-subject

rotary presses bearing Anderson-Priest treasury signatures. These were

first released to the public on October 1, 1957.

269

October 1, 1957. The notes were $1 Series of 1957, the first U.S. currency printed on 32-subject

rotary presses. This is the history of how this came about.

National Motto on Coins and Paper Money

This section is reproduced verbatim from the U.S. Treasury web site.

The motto IN GOD WE TRUST was placed on United States coins largely because of the

increased religious sentiment existing during the Civil War. Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P.

Chase received many appeals from devout persons throughout the country, urging that the United

States recognize the Deity on United States coins. From Treasury Department records, it appears

that the first such appeal came in a letter dated November 13, 1861. It was written to Secretary

Chase by Rev. M.R. Watkinson, Minister of the Gospel from Ridleyville (present day Prospect

Park), Pennsylvania, and read:

Dear Sir: You are about to submit your annual report to the Congress respecting the affairs

of the national finances.

One fact touching our currency has hitherto been seriously overlooked. I mean the

recognition of the Almighty God in some form on our coins.

You are probably a Christian. What if our Republic were not shattered beyond

reconstruction? Would not the antiquaries of succeeding centuries rightly reason from our past

that we were a heathen nation? What I propose is that instead of the goddess of liberty we shall

have next inside the 13 stars a ring inscribed with the words PERPETUAL UNION; within the

ring the allseeing eye, crowned with a halo; beneath this eye the American flag, bearing in its

field stars equal to the number of the States united; in the folds of the bars the words GOD,

LIBERTY, LAW.

This would make a beautiful coin, to which no possible citizen could object. This would

relieve us from the ignominy of heathenism. This would place us openly under the Divine

protection we have personally claimed. From my hearth I have felt our national shame in

disowning God as not the least of our present national disasters.

To you first I address a subject that must be agitated.

As a result, Secretary Chase instructed James Pollock, Director of the Mint at Philadelphia,

to prepare a motto, in a letter dated November 20, 1861:

It was found that the Act of Congress dated January 18, 1837, prescribed the mottoes and

devices that should be placed upon the coins of the United States. This meant that the mint could

make no changes without the enactment of additional legislation by the Congress. In December

1863, the Director of the Mint submitted designs for new one-cent coin, two-cent coin, and three-

cent coin to Secretary Chase for approval. He proposed that upon the designs either OUR

COUNTRY; OUR GOD or GOD, OUR TRUST should appear as a motto on the coins.

In a letter to the Mint Director on December 9, 1863, Secretary Chase stated:

I approve your mottoes, only suggesting that on that with the Washington obverse the motto

should begin with the word OUR, so as to read OUR GOD AND OUR COUNTRY. And on that

with the shield, it should be changed so as to read: IN GOD WE TRUST.

The Congress passed the Act of April 22, 1864. This legislation changed the composition

of the one-cent coin and authorized the minting of the two-cent coin. The Mint Director was

directed to develop the designs for these coins for final approval of the Secretary. IN GOD WE

TRUST first appeared on the 1864 two-cent coin.

Another Act of Congress passed on March 3, 1865. It allowed the Mint Director, with the

Secretary’s approval, to place the motto on all gold and silver coins that “shall admit the inscription

thereon.” Under the Act, the motto was placed on the gold double-eagle coin, the gold eagle coin,

and the gold half-eagle coin. It was also placed on the silver dollar coin, the half-dollar coin and

270

the quarter-dollar coin, and on the nickel three-cent coin beginning in 1866. Later, Congress passed

the Coinage Act of February 12, 1873. It also said that the Secretary “may cause the motto IN

GOD WE TRUST to be inscribed on such coins as shall admit of such motto.”

The use of IN GOD WE TRUST has not been uninterrupted. The motto disappeared from

the five-cent coin in 1883, and did not reappear until production of the Jefferson nickel began in

1938. Since 1938, all United States coins bear the inscription. Later, the motto was found missing

from the new design of the double-eagle gold coin and the eagle gold coin shortly after they

appeared in 1907. In response to a general demand, Congress ordered it restored, and the Act of

May 18, 1908, made it mandatory on all coins upon which it had previously appeared. IN GOD

WE TRUST was not mandatory on the one-cent coin and five-cent coin. It could be placed on

them by the Secretary or the Mint Director with the Secretary’s approval.

The motto has been in continuous use on one-cent coins since 1909, and on the ten-cent

coin since 1916. It also has appeared on all gold and silver dollar, half-dollar and quarter-dollar

coins struck since July 1, 1908.

President Eisenhower approved a Joint Resolution of the 84th Congress on July 30, 1956

declaring IN GOD WE TRUST as the national motto of the United States. IN GOD WE TRUST

was first used on paper money in 1957, when it appeared on the one-dollar silver certificate. The

first paper currency bearing the motto entered circulation on October 1, 1957. The Bureau of

Engraving and Printing (BEP) was converting to the dry intaglio printing process. During this

conversion, it gradually included IN GOD WE TRUST in the back design of all classes and

denominations of currency.

As a part of a comprehensive modernization program the BEP successfully developed and

installed new high-speed rotary intaglio printing presses in 1957. These allowed BEP to print

currency by the dry intaglio process, 32 notes to the sheet. One-dollar silver certificates were the

first denomination printed on the new high-speed presses. They included IN GOD WE TRUST as

part of the reverse design as BEP adopted new dies according to the law. The motto also appeared

on one-dollar silver certificates of the 1957-A and 1957-B series.

BEP prints United States paper currency by an intaglio process from engraved plates. It

was necessary, therefore, to engrave the motto into the printing plates as a part of the basic

engraved design to give it the prominence it deserved.

One-dollar silver certificates series 1935, 1935-A, 1935-B, 1935-C, 1935-D, 1935-E, 1935-

F, 1935-G, and 1935-H were all printed on the older flat-bed presses by the wet intaglio process.

P.L. 84-140 recognized that an enormous expense would be associated with immediately replacing

the costly printing plates. The law allowed BEP to gradually convert to the inclusion of IN GOD

Figure 2. The first use of “In God

We Trust” on coins was in 1864 on

the 2 cent pieces.

271

WE TRUST on the currency. Accordingly, the motto is not found on series 1935-E and 1935-F

one-dollar notes. By September 1961, IN GOD WE TRUST had been added to the back design of

the Series 1935-G notes. Some early printings of this series do not bear the motto. IN GOD WE

TRUST appears on all series 1935-H one-dollar silver certificates.

Below is a listing by denomination of the first production and delivery dates for currency

bearing IN GOD WE TRUST:

Production Delivery

$1 FRN Feb 12, 1964 Mar 11, 1964

$5 LT Jan 23, 1964 Mar 2, 1964

$5 FRN Jul 31, 1964 Sep 16, 1964

$10 FRN Feb 24, 1964 Apr 24, 1964

$20 FRN Oct 7, 1964 Oct 7, 1964

$50 FRN Aug 24, 1966 Sep 28, 1966

$100 FRN Aug 18, 1966 Sep 27, 1966

Origin of the Motto on Paper Money

The impetus for getting the motto on U.S.

paper money resulted from a campaign orchestrated

by Matthew H. Rothert, a Christian Scientist, coin

collector, and founder of the Camden Furniture

Company of Camden, Arkansas. Rothert eventually

became president of the American Numismatic

Association from 1965 to 1967,

The following is abstracted from the “In God

We Trust” web site, that illustrated key documents

from Rothert’s crusade.

Rothert floated the idea while president of the

Arkansas Numismatic Society at a quarterly meeting

in Mountain Home, Arkansas, on November 1, 1953.

He then wrote Secretary of the Treasury George

Humphrey on November 25, 1953 suggesting the

idea, followed by a letter to President Eisenhower

five days later. Rothert received a reply from Edward

F. Bartelt, Financial Assistant Secretary, dated

February 3, 1954, in which Bartelt stated:

As you know, provision was made by law in 1865 for placing this motto [In God We Trust] on

coins. Another act providing for the inscription became law in 1908. During debate on the 1908

measure, the suggestion was made that the motto be placed on currency, but no action was taken

on this point. From the record of this legislation, which has been reached that a clear precedent

was set for Congressional action in such a matter, and that Secretary of the Treasury should not

undertake to act individually.