Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

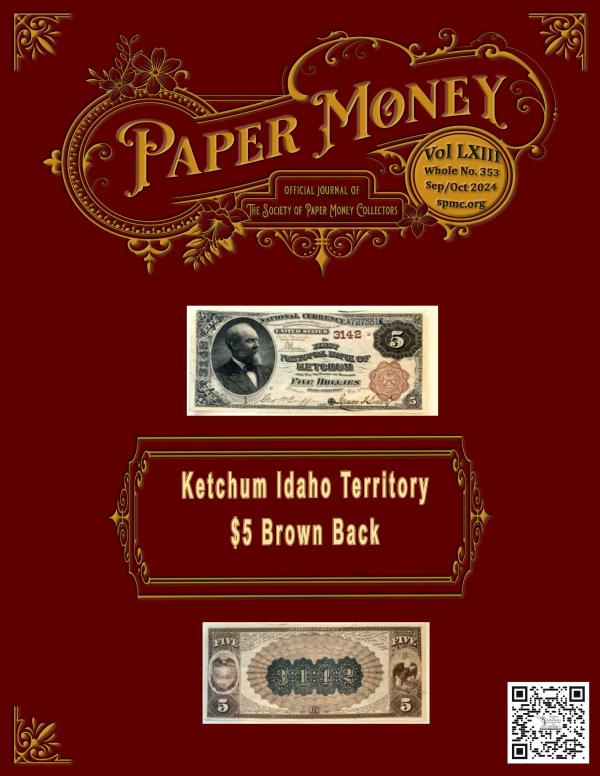

#1 5$ Brown Back-Ketchum, Idaho Territory--Peter Huntoon

John Douglas-New Orleans Engraver--Mark Coughlan

National Bank Note Circulation Decline--Peter Huntoon

Miss Blackey-The Most Beautiful Woman in Virginia--Tony Chibbaro

CIA Counterfeit Cuban Banknotes of 1961--Roberto Menchaca

Hastings Nebraska National Bank Robbery

WWII Japanese-American Internment Camp Money-Pt. 2--Steve Feller, et al

The Tishomingo Hotel--James Ehrhardt

"Eighteen Ninety-Four"--Bob Laub

Hand-Signed History-A Book Review--Michael McNeil

official journal of

The Society of Paper Money Collectors

Ketchum Idaho Territory

$5 Brown Back

LEGENDARY COLLECTIONS | LEGENDARY RESULTS | A LEGENDARY AUCTION FIRM

Exceptional Prices Realized from

Stack’s Bowers Galleries

Consign Your U.S. Currency to Our November 2024 Showcase Auction

The Official Auctioneer of the Whitman Coin & Collectibles Expo

Auction: November 18-22, 2024 • Consignment Deadline: September 23, 2024

CC-34. Continental Currency. May 9, 1776. $4.

PCGS Banknote Superb Gem Uncirculated 68 PPQ.

Realized: $18,000

T-45. Confederate Currency. 1862 $1.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Realized: $14,400

Fr. 1700. 1933 $10 Silver Certificate.

PCGS Banknote Superb Gem Uncirculated 67 PPQ.

Low Serial Number.

Realized: $99,000

Fr. 2210-Hlgs. 1928 Light Green Seal

$1000 Federal Reserve Note. St. Louis.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Realized: $43,200

Fr. 2402H. 1928 $20 Gold Certificate Star Note.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Realized: $38,400

Fr. 2405. 1928 $100 Gold Certificate.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 66 EPQ.

Realized: $192,000

Fr. 2407. 1928 $500 Gold Certificate.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Realized: $216,000

Fr. 2221-K. 1934 $5000 Federal Reserve Note.

Dallas. PCGS Banknote Choice Very Fine 35.

Realized: $174,000

Fr. 2301mH. 1934 $5 Hawaii Emergency

Star Mule Note. San Francisco.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 66 EPQ.

Realized: $52,800

Fr. 2200-Jdgs. 1928 Dark Green Seal

$500 Federal Reserve Note. Kansas City.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Realized: $43,200

Fr. 2201-A. 1934 Dark Green Seal

$500 Federal Reserve Note. Boston.

PCGS Banknote Superb Gem Uncirculated 68 PPQ.

Realized: $48,000

Fr. 2. 1861 $5 Demand Note.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Realized: $408,000

Contact Our Experts for More Information Today!

Peter Treglia: 949.748.4828 • Michael Moczalla: 949.503.6244 • Consign@StacksBowers.com

America’s Oldest and Most Accomplished Rare Coin Auctioneer

1550 Scenic Ave., Ste. 150, Costa Mesa, CA 92626 • 949.253.0916 • Info@StacksBowers.com

470 Park Ave., New York, NY 10022 • 212.582.2580 • NYC@stacksbowers.com

84 State St. (at 22 Merchants Row), Boston, MA 02109 • 617.843.8343 • Boston@StacksBowers.com

1735 Market St. (18th & JFK Blvd.), Philadelphia, PA 19103 • 267.609.1804 • Philly@StacksBowers.com

Info@StacksBowers.com • StacksBowers.com

California • New York • Boston • New Hampshire • Oklahoma • Philadelphia

Sacramento • Virginia • Hong Kong • Copenhagen • Paris • Vancouver

SBG PM Nov2024 Consign 240901

317 #1 5$ Brown Back-Ketchum, Idaho Territory--Peter Huntoon

324 John Doughlas-New Orleans Engraver--Mark Coughlan

332 National Bank Note Circulation Decline--Peter Huntoon

342 Miss Blackey-The Most Beautiful Woman in Virginia--Tony CHibbaro

344 CIA Counterfeit Cuban Banknotes of 1961--Roberto Menchaca

349 Hastings Nebraska National Bank Robbery

352 WWII Japanese-American Internment Camp Money-Pt. 2--Steve Feller, et al

359 The Tishomingo Hotel--James Ehrhardt

369 "Eighteen Ninety-Four"--Bob Laub

376 Hand-Signed History-A Book Review--Michael McNeil

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

312

Columns

Advertisers

SPMC Hall of Fame

The SPMC Hall of Fame recognizes and honors those individuals who

have made a lasting contribution to the society over the span of many years.

Charles Affleck

Walter Allan

Mark Anderson

Doug Ball

Hank Bieciuk

Joseph Boling

F.C.C. Boyd

Michael Crabb

Forrest Daniel

Martin Delger

William Donlon

Roger Durand

C. John Ferreri

Milt Friedberg

Robert Friedberg

Len Glazer

Nathan Gold

Nathan Goldstein

James Haxby

John Herzog

Gene Hessler

John Hickman

William Higgins

Ruth Hill

Peter Huntoon

Brent Hughes

Glenn Jackson

Don Kelly

Lyn Knight

Chet Krause

Allen Mincho

Clifford Mishler

Barbara Mueller

Judith Murphy

Dean Oakes

Chuck O'Donnell

Roy Pennell

Albert Pick

Fred Reed

Matt Rothert

John Rowe III

From Your President

Editor Sez

New Members

Uncoupled

Cherry Picker Corner

Obsolete Corner

Quartermaster

Small Notes

Chump Change

Robert Vandevender 314

Benny Bolin 315

Frank Clark 316

Joe Boling & Fred Schwan 362

Robert Calderman 366

Robert Gill 371

Michael McNeil 373

Jamie Yakes 378

Loren Gatch 379

Stacks Bowers Galleries IFC

Pierre Fricke 312

Bob Laub 322

Lyn Knight 323

PCGS-C 331

Higgins Museum 340

World BankNote Auctions 341

Fred Bart 346

FCCB 346

Whatnot 351

PM of the U.S. 358

Greysheet 361

Bill Litt 361

PCDA IBC

Heritage Auctions OBC

Fred Schwan

Neil Shafer

Herb& Martha Schingoethe

Austin Sheheen, Jr.

Hugh Shull

Glenn Smedley

Raphael Thian

Daniel Valentine

Louis Van Belkum

George Wait

D.C. Wismer

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

313

Officers & Appointees

ELECTED OFFICERS

PRESIDENT Robert Vandevender II

rvpaperman@aol.com

VICE-PRES/SEC'Y Robert Calderman

gacoins@earthlink.net

TREASURER Robert Moon

robertmoon@aol.com

BOARD OF GOVERNORS

APPOINTEES

PUBLISHER-EDITOR

Benny Bolin smcbb@sbcglobal.net

ADVERTISING MANAGER

Wendell Wolka purduenut@aol.com

Megan Reginnitter mreginnitter@iowafirm.com

LIBRARIAN

Jeff Brueggeman

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

Frank Clark frank_clark@yahoo.com

IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT

Shawn Hewitt

WISMER BOOk PROJECT COORDINATOR

Pierre Fricke

From Your President

Robert Vandevender IIFrom Your President

Shawn Hewitt

Paper Money * July/August 2020

6

jeff@actioncurrency.com

LEGAL COUNSEL

Robert Calderman gacoins@earthlink.com

Matt Drais stockpicker12@aol.com

Mark Drengson markd@step1software.com

Jerry Fochtman jerry@fochtman.us

Pierre Fricke pierrefricke@buyvingagecurrency.com

Loren Gatch lgatch@uco.edu

Derek Higgins derekhiggins219@gmail.com

Raiden Honaker raidenhonaker8@gmail.com

William Litt billitt@aol.com

Cody Regennitter cody.regennitter@gmail.com

Andy Timmerm

Wendell Wolka purduenut@aol.com

an andrew.timmerman@aol.com

During our last Long Beach Expo show in June, I learned something new. Don

Kagin stopped by our SPMC table and we had a very nice discussion. Don

mentioned that he was preparing to write a new article or book about Canadian

Card Money. I have never heard of it before and was intrigued. From what I

understand, due to an actual shortage of real currency in “New France,” playing

cards that were available were cut up and marked with an official stamp on them

and they were used to pay the troops. Evidently there were several series of the

money issued but only a few examples survive from the last issue. I am looking

forward to Don’s article to come out to learn more and do hope he chooses Paper

Money Magazine for publication.

My friend Alan Bailey responded to my last President’s column with an email

titled “some lawyer out there” to explain why it is ok for businesses to not accept

legal tender cash for transactions. I asked him to write an article for Paper

Money Magazine and he is working on getting permission from his employer to

write that article. I hope he is able to write it, and I am looking forward to

reading about it in a future issue of PM.

The ANA show in Chicago went very well and I, once again, purchased a

bronze bar for my “railroad track” ANA medal. I have seen many tracks that are

a couple of feet long but mine is not so impressive. My first ANA show was in

1991, so my tracks aren’t that long. Several of our members were in attendance.

On Thursday evening, August 8th, several of us walked down to the Capital

Grille for a nice dinner. Those in attendance were Vice President Calderman,

Member Lauren Calderman, Past President Shawn Hewitt, Member Nancy

Purington, Member Billy Baeder and me. We all seemed to have a good time

right up until the impressive check arrived for payment!

Once again, we participated in the ANA’s Treasure Trivia Game (scavenger

hunt) for children. We used the same question we used at FUN last time where

we asked on what currency does the portrait of Abraham Lincoln appear, with

three correct choices and an all of the above answer. After each child answered

the question, we rewarded them with the choice of either a note from Nepal

featuring a yak, or a note from Mongolia featuring horses. It was funny, but most

of the boys wanted the yak note, and the girls selected the horses. We will come

up with a new question for the upcoming FUN show next January.

We added six new members to our society this week including the new

President of the ANA, Thomas Uram. Mr. Uram is interested in increasing the

exposure of paper money within the ANA and asked me to see if I could locate a

member willing to write a nice article on a paper money subject for publication in

the Numismatist. If any of our members are interested, please send me an email.

At our last governors meeting we voted to give a $1,000 contribution check to

the Higgins Museum seminar and presented the check at the ANA show to

curator George Cuhaj.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

314

Terms and Conditions

The Society of Paper Money Collectors (SPMC) P.O. Box 7055,

Gainesville, GA 30504, publishes PAPER MONEY (USPS 00‐

3162) every other month beginning in January. Periodical

postage is paid at Hanover, PA. Postmaster send address

changes to Secretary Robert Calderman, Box 7055, Gainesville,

GA 30504. ©Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc. 2020. All

rights reserved. Reproduction of any article in whole or part

without written approval is prohibited. Individual copies of this

issue of PAPER MONEY are available from the secretary for $8

postpaid. Send changes of address, inquiries concerning non ‐

delivery and requests for additional copies of this issue to

the secretary.

MANUSCRIPTS

Manuscripts not under consideration elsewhere and

publications for review should be sent to the editor. Accepted

manuscripts will be published as soon as possible, however

publication in a specific issue cannot be guaranteed. Opinions

expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect those of the

SPMC. Manuscripts should be submitted in WORD format via

email (smcbb@sbcglobal.net) or by sending memory stick/disk

to the editor. Scans should be grayscale or color JPEGs at

300 dpi. Color illustrations may be changed to grayscale at the

discretion of the editor. Do not send items of value.

Manuscripts are submitted with copyright release of the author

to the editor for duplication and printing as needed.

ADVERTISING

All advertising on space available basis. Copy/correspondence

should be sent to editor.

All advertising is pay in advance. Ads are on a “good faith”

basis. Terms are “Until Forbid.”

Ads are Run of Press (ROP) unless accepted on a premium

contract basis. Limited premium space/rates available.

To keep rates to a minimum, all advertising must be prepaid

according to the schedule below. In exceptional cases where

special artwork or additional production is required, the

advertiser will be notified and billed accordingly. Rates are

not commissionable; proofs are not supplied. SPMC does not

endorse any company, dealer, or auction house. Advertising

Deadline: Subject to space availability, copy must be received

by the editor no later than the first day of the month

preceding the cover date of the issue (i.e. Feb. 1 for the

March/April issue). Camera‐ready art or electronic ads in pdf

format are required.

ADVERTISING RATES

Editor Sez

Benny Bolin

Required file submission format is composite PDF v1.3

(Acrobat 4.0 compatible). If possible, submitted files should

conform to ISO 15930‐1: 2001 PDF/X‐1a file format standard.

Non‐ standard, application, or native file formats are not

acceptable. Page size: must conform to specified publication

trim size. Page bleed: must extend minimum 1/8” beyond

trim for page head, foot, and front. Safety margin: type and

other non‐bleed content must clear trim by minimum 1/2”.

Advertising c o p y shall be restricted to paper currency, allied

numismatic material, publications, and related accessories.

The SPMC does not guarantee advertisements, but accepts

copy in good faith, reserving the right to reject objectionable

or inappropriate material or edit copy. The SPMC

assumes no financial responsibility for typographical

errors in ads but agrees to reprint that portion of an ad in

which a typographical error occurs.

Benny (aka goompa)

Space

Full color covers

1 Time

$1500

3 Times

$2600

6 Times

$4900

B&W covers 500 1400 2500

Full page color 500 1500 3000

Full page B&W 360 1000 1800

Half‐page B&W 180 500 900

Quarter‐page B&W 90 250 450

Eighth‐page B&W 45 125 225

Welcome to the family--OLIVIA JO BOLIN!!

August 2, 2024. 7# and 20 inches.

Here is grandpa (goompa) and Olivia.

Now, on to paper money stuff. Boy, is it HOT! Reminds me of a

summer we had in the 70's when it got to 110 here. I don't expect to

hear much complaining when it gets wintry and cold! I hope you

are staying safe and out of the heat. Remember--drink lots of fluid

(not the beer kind). The hobby seems to be hot also. I have attended

a few local shows and they have been busy and bustling. Reports

from the recent ANA show were also very encouraging and it

seems that we are doing fine as a hobby. How about doing a newly

imprinted "goompa" a favor? While you are sitting in the A/C

biding your time to winter, write me an article. I am running kind

of low on 3-5 page articles. It is really a charge getting to see your

name in print! Can't write you say? Send me facts and I will turn it

into an article and put your name on the byline.

Recently, Robert Calderman, Cody Regenniter and Wendell

Wolka all stood unopposed for re-election to the board. However,

we still have one spot open so if you are interested, direct your

inquiry to one of the officers.

I want to send a BIG shout-out to Jim Fitzgerald, the bourse

chairman of the Texas Numismatic Association show that was held

in late June in Conroe Texas. It was a great show and I was there

with two exhibits and Robert Calderman was there as a dealer.

Well, it seems there were a couple of empty tables, so Robert

inquired with Jim about the SPMC using one and he gave the club a

table for free! Thank you Jim!! We recruited two new members at

the show and made a lot of other promising contacts.

Speaking of shows--winter FUN is just around the corner. I know

it is hard to think of a winter show, but January will be here soon.

Make plans to attend. The SPMC will have their yearly meetings at

the show, including the awards breakfast and Tom Bain Raffle (mix

'em up)! Also, plan on placing an exhibit. The more exhibits we can

have there, the more exposure we can have for paper money. We

will soon be announcing our meeting times and activities as well as

starting our annual on-line article awards competition. Be looking

for that and vote, vote, vote (only once per member though)!

Due to my work (high school RN) and other commitments, I am

unable to attend many non-local shows. This is a bummer for me,

so I have been somewhat satisfying my paper money desires by

going to some of the social media groups (I only do facebook).

There is a national bank note group, the FCCB has a fractional

group, there is an obsolete currency group and I would imagine

others if you just investigate. These are fun and have some very

insightful information in them.

Till next time! Stay safe and enjoy summer!

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

315

The Society of Paper Money

Collectors was organized in 1961 and

incorporated in 1964 as a non-profit

organization under the laws of the

District of Columbia. It is

affiliated with the ANA. The

Annual Meeting of the SPMC is

held in June at the International

Paper Money Show. Information

about the SPMC, including the

by-laws and activities can be

found at our website--

www.spmc.org. The SPMC does

not does not endorse any dealer,

company or auction house.

MEMBERSHIP—REGULAR and

LIFE. Applicants must be at least 18

years of age and of good moral

character. Members of the ANA or

other recognized numismatic

societies are eligible for membership.

Other applicants should be sponsored

by an SPMC member or provide

suitable references.

MEMBERSHIP—JUNIOR.

Applicants for Junior membership

must be from 12 to 17 years of age

and of good moral character. A parent

or guardian must sign their

application. Junior membership

numbers will be preceded by the letter

“j” which will be removed upon

notification to the secretary that the

member has reached 18 years of age.

Junior members are not eligible to

hold office or vote.

DUES—Annual dues are $39. Dues

for members in Canada and Mexico

are $45. Dues for members in all

other countries are $60. Life

membership—payable in installments

within one year is $800 for U.S.; $900

for Canada and Mexico and $1000

for all other countries. The Society

no longer issues annual membership

cards but paid up members may

request one from the membership

director with an SASE.

Memberships for all members who

joined the Society prior to January

2010 are on a calendar year basis

with renewals due each December.

Memberships for those who joined

since January 2010 are on an annual

basis beginning and ending the

month joined. All renewals are due

before the expiration date, which can

be found on the label of Paper

Money. Renewals may be done via

the Society website www.spmc.org

or by check/money order sent to the

secretary.

WELCOME TO OUR

NEW MEMBERS!

BY FRANK CLARK

SPMC MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

NEW MEMBERS 7/05/2024

Dues Remittal Process

Send dues directly to

Robert Moon

SPMC Treasurer

403 Gatewood Dr.

Greenwood, SC 29646

Refer to your mailing label for when

your dues are due.

You may also pay your dues online at

www.spmc.org.

15726 Fred Barton III, Paper Money Forum

15727 Zachary Wilson-Fetrow, Frank Clark

15728 Douglas Adams, Website

15729 Caleb Audette, Susan Bremer

15730 Sam Holder, Website

15731 Gary Hannig, Robert Calderman

15732 Shimon Nussbaum, Frank Clark

15733 Brian Morrow, Robert Calderman

15734 Klaus Andreas Riegler, Website

15735 Mark Pogue, Robert Calderman

15736 Spencer Morgan, Website

15737 Ryan Guderian, Cody Regenniter

REINSTATEMENTS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

None

Note--new

addressNote--new

address

NEW MEMBERS 8/05/2024

15714 Fred Pasternak, Bob Kvederas

15715 Michael Guzzi, Website

15716 Scott Allinson, Website

15717 Michael Ettner, Rbt Vandevender

15718 Kelly Burgess, Robert Calderman

15719 Jose Roman, Website

15720 Teresa Prewitt, Gary Dobbins

15721 David Stevenson, Frank Clark

15722 Steven Tormollan, Rbt Calderman

15723 Christine Faecke, Frank Clark

15724 Neil Musante, Website

15725 Ralph Stenzel, Nationals

REINSTATEMENTS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

None

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

316

Uncirculated $5 #1 Brown Back

Ketchum, Idaho Territory

Bank owner and president Isaac Ives Lewis was one of those quintessential entrepreneurs of

western lore who through personal tenacity clawed his way from abject poverty to riches in the western

territories as they opened.

Everything pertaining to Lewis’ life presented here is from Lewis (1892) unless a particular fact is

explicitly credited to another source.

Isaac Lewis was born February 7, 1825 in Wallingsford Hill, Litchfield County, Connecticut. In

1831, his family, which at the time included his mother, sister, older brother Eli and an uncle, immigrated

to southwestern Illinois to join his father and three uncles who left a year earlier. Their route was via

Hartford, New York City, the Erie Canal to Buffalo, across Lake Erie to Sandusky, overland through Ohio,

Indiana and Illinois. Often, they provisioned themselves by hunting small game along the way.

Figure 1. Note acquired by Jess Lipka in 2024 from the first sheet of 1,469 5-5-5-5 Series of 1882 brown back

sheets sent to The First National Bank of Ketchum, Idaho Territory to support a circulation of $11,500 during

its life. It is the highest grade note of nine currently reported from the territory. Signers are Isaac Ives Lewis,

president; George W. Griffin, cashier.

The Paper

Column

Peter Huntoon

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

317

The family rented a farm in Marine

Settlement for two years. The settlement, 25

miles northeast of St. Louis and now named

Marine, had been founded in 1819 by a group

of sea captains from Connecticut.

Isaac’s mother died in 1831. Schooling

was minimal and intermittent. He had attended

grammar school in Connecticut during 1828-

1831 where he learned to read as well as stints

in 1832 and the summer of 1834 in Illinois. In

time, he developed into a voracious reader

consuming anything in print that he could get

his hands on.

In the spring of 1834, his father left for

Galena, Mineral Point and Dubuque where he

hired on as a miner. Issac and his sister were

fobbed off on his uncle Jo who had a farm out

on the prairie. At eight years old, Isaac found

himself serving as a full-time farm laborer. He

recalled “I was always hungry when I lived with

him and many times, he would eat about all

there was on the table and I would have to leave

it hungry—yes, hungry as a wolf. * * * Well, Uncle Jo at that time was a hard master. Aunt Anna was kind

to us children and often screened us from Uncle and fed us when he was absent.”

In 1834, he and his sister moved on to live with his Uncle Will and Aunt Eunice until 1836. They

operated an inn on the stage route between St. Louis and Vandalia, the then capital of Illinois. Issac attended

school during January and February 1836 where he learned to write at age 11. His Uncle Will hired him

out for the summer of 1836 as a full-time laborer on a farm owned by a man named William Gerkie. His

work plowing with teams of horses or oxen was the equal of any man.

His father and uncle returned in 1836 from a profitable mining venture and their extended family

gathered around them including a grandmother, Isaac, his brother Eli and his sister. They returned to Marine

Settlement in 1839, where they rented a productive farm for the next three years. The boys attended school

for three months during the winters.

Isaac proved to be exceptionally entrepreneurial during these formative years trapping, shooting

and dressing game, tanning leather, growing produce, etc. At 24, he ventured up the Mississippi River to

join his brother Eli in surveying the St. Anthony Falls townsite for a developer named William Marshall.

Isaac moved on to plat the first lots in adjacent Minneapolis where he lived on that piece of ground in a log

cabin during the summer of 1849, yielding for him the distinction of being the first settler to live in

Minneapolis. He returned to St. Anthony where at age 25 he managed a mercantile store, was appointed

Assessor of Ramsey County in 1850, and married Georgiana Christmas. He was elected justice of the Peace

in 1852. His first formal business venture came in 1854 when he partnered with another man to purchase a

grocery store in St. Anthony Falls that was renamed I. I. Lewis & Co. This business was soon moved across

the river to Minneapolis.

The capital that he possessed was his acumen, skill at business, self-confidence and tireless work

ethic. He had the ability to recognize potential business opportunities and tenacity to organize the assets

necessary to pursue them. He was learning the power of money and how to manage credit. The pattern that

followed was to buy and sell a succession of businesses, increasingly focus on land deals and pursue mining

opportunities.

A speculative fever grew during the winter of 1855-6 for developing townsites west of the

Mississippi River. To this end, Lewis and nine others organized a company that claimed, plated and

established Rapid City, Union City and Watertown. By then, he had sufficient wealth and property to

Figure 2. Isaac Ives Lewis, 1825-1903, founder of The First

National Bank of Ketchum, Idaho Territory. Ketchum

Community Library photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

318

weather the Panic of 1857-8. He moved his family

to his Watertown hotel in late 1858 where he

stayed during the Civil War, which he avoided by

paying the required bounty.

Not all his business pursuits went well. In

1865, the state geologist of Minnesota released a

report advising that gold-bearing quartz veins

existed in the vicinity of Lake Vermillion, 100

miles north of St. Paul. Lewis joined this gold rush

as part of a company of 70 men that had been

organized in St. Paul, which involved transporting

expensive provisions and equipment through the

wilderness. They left St. Paul November 1865 and

by summer of 1866 had established 10 claims. The

company suffered near famine conditions in the

process and their reward was to find that the ore

was uneconomic. Lewis lost $4,000 in the venture,

a considerable sum in 1866,

As a resident of Watertown, he served in

the 1868-1869 Minnesota House of

Representatives representing Carver County.

His appetite for gold was not quenched,

however. He was ripe for a scam that came in the

form of a man named Robinson, who came to

Minnesota in the winter of 1870-1 with specimens

of rich gold and silver ores from what he claimed were his prospects in the mountains near Coeur d’ Alene,

Idaho. His pitch was that he was terminally ill with consumption and needed just enough money to see him

through the rest of his days in exchange for his claims. He would be glad to organize a party of men to

funds his needs and take them there at $200 apiece. Lewis joined some 40 or so others in the quest.

As the party moved through Montana, suspicions began to grow. A party of three men accompanied

Robinson to Helena where he was to make arrangements for the party to continue to Missoula. He gave his

escorts the slip at Helena by exiting their hotel by a side door where he hoofed it to the nearest stage station

on the road to Corinne, Utah. He caught the stage the next day at noon.

As fate would have it, the stage stopped at Captain Cook’s roadhouse in Boulder Valley for dinner.

A patron there recognized Robinson as the man who fleeced his party, which had originated in Montana,

using the same gambit two years previously. With the help of Cook, Robinson was relieved of all his money

except $100 and advised to leave the country. This act of partial restitution for the benefit of the Montana

victims did little good for the Minnesota folks. They disbanded and disbursed from Helena. Lewis stayed

on in Montana and tried his hand at placer mining.

Lewis was hooked on mining and the Rocky Mountain west. He circulated between Idaho and

Montana for some years setting up several mercantile and drug stores as well as investing in mines. One of

the first that he bought into was the Legal Tender Mine (silver) in the Argenta mining district of

southwestern Montana (Minneapolis Star Tribune, Oct 16, 1872). He served in the Montana Territorial

Legislature in 1875 where he introduced bills to promote the construction of railroads in Montana. Lewis

perceived great opportunity in the mining district at Butte and spent much time there tending to claims.

C. D. Corbin of the First National Bank of Butte hired Lewis to take over as superintendent of the

Rumley and Hope mines there and Lewis came on board March 1, 1876. He was 51 at the time. It was a

major operation so to be selected to run it recognized the esteem Lewis had earned and the distance he had

come with minimal schooling. However, he held the position for only about a year, being tempted away by

a prospector named Levi Allen working out of Helena.

Allan was offering to sell a silver lode called the Peacock Mine that he had claimed in 1862 in the

Figure 3. Isaac Ives Lewis as a young man.

Ancestry.com photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

319

mountains in the remote northwest corner of what is now Adams County in southwestern Idaho. Ore

samples that he had assayed at 50 percent copper with some gold and silver. Samuel T. Hauser, owner of

The First National Bank of Helena and future governor of Montana Territory, also was interested in the

play and commissioned Lewis as his agent to look at the property (Mitchell, 1997, p. 9).

Allan, Lewis and a small party of men including Lewis’ son John departed Helena at the end of

July, 1877 with a wagon filled with provisions and tools for the arduous 600-mile, 65-day journey to the

prospect. They passed through Boise City September 7th where they replenished their provisions. Upon

arriving at the prospect, they spent 10 or 12 days staking the claim, staking additional claims in the vicinity

and collecting samples for assaying. Both Hauser and Lewis acquired an interest in the Peacock Mine.

Upon returning to Helena, Hauser hired Lewis to return to Butte to buy ore for his S. T. Hauser &

Co. Bank at Butte. The assistant cashier of the bank pulled Lewis aside with the proposition that he would

teach him how to run the bank. Thereupon he immediately showed Lewis how to make up the day’s work.

This was the first time Lewis had ever been on that side of a bank counter. The cashier told him to come

back the next day at 4 pm to do the same saying he probably could get him posted to run the bank. Lewis

thereupon found himself hired as bookkeeper and assistant to Hauser in addition to buying ore and

handling the silver and gold bullion for a few silver mills.

As at the Ramsey Mine, Lewis became restless by late 1879 claiming attention to the business of

the bank was taking a toll on his health. Meanwhile, he was hearing glowing reports from returning

prospectors about their finds in the Wood River country of Idaho. That area was not overrun by prospectors

yet. The urge was overwhelming so he took a 60-day leave of absence on the pretense of his health from

Hauser’s operation.

On April 5, 1880, Lewis, his son John and Charles Swan set off for the Wood River Valley. In

business, Lewis served as the point of the spear, not the handle. He was the risktaker who excelled at

spotting opportunities, launching new ventures and then moving on. In mining he relished the rough and

tumble of buying claims, even staking claims, and pulling together the capital, men and equipment to exploit

them. It appears from his tracks that when he found himself a cog in an established corporation where his

job was simply to keep the operation humming or in a bank largely pushing paper, it wasn’t a good fit.

Besides, Lewis was used to being the principal in his ventures.

Here he was at age 55 on the make again, this time embarked on a life-changing oddesy that would

enshrine him in western lore. All his ambitions, talents and tenacity converged to bring this to fruition.

The expedition consisted of Isaac Lewis, his son John Lewis and Charles Awan. Their wagon held

their provisions, tents, mining tools and Lewis’ assay and surveying equipment. Lewis was jumping the

gun because spring rain and snow storms lay ahead and plenty of accumulated winter snow became

especially troublesome on passes they had to navigate. On May 3rd they pitched their tents on the site that

would become Ketchum, probably the first tents ever on the place. They had traveled some 400 miles from

Helena.

A party of six or so had passed through the day before without staying the night and laid claim to

the townsite that they called Leadville. They left a piece of brown paper with a sketch of the townsite with

numbered blocks and lots as well as placing a few stakes in the snow to mark Main Street. Lewis’ party

occupied four lots paying someone $8 before setting up their tents. William Greenhow arrived the next day,

chose a lot and set up a saloon. Lewis surveyed-in the streets and lots and set up a tent for the first assay

office in the Wood River country. John Lewis and Charles Awan collected logs for the first house. People

began to arrive by the hundreds to look the place over. Those who bought lots had to shovel the snow off

well into May to start building.

In nearby Elkhorn Gulch where John Keeler had staked a viable claim, Lewis in due course

purchased it for $12,000. Ultimately Hauser financed the purchase. The ore from that mine was the first

shipped from the region for smelting, an event that took place in July 1880 via wagon to Kelton, Utah and

on to Salt Lake City by rail.

Lewis was elected Justice of the Peace in August 1880. The town name Leadville was changed to

Ketchum, after David Ketchum, a trapper and guide in the area.

Lewis arranged for a man to go 4 miles up Trail Creek in April 1881 to lay claim to a water right

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

320

for the town. At the same time, Lewis also laid claim to and fenced about 700 acres of tillable land up Trail

Creek that was then used for hay and grain. In the summer of 1881, Lewis opened a drug store, eventually

expanded it with groceries, and later bought half interest in a mercantile store. Ketchum was taking shape,

all the while with Lewis trading in mines and prospects. Lewis emerged as Ketchum’s leading citizen.

It was only a matter of time before he opted to open a bank. To this end he went to New York

during December 1883 to organize a national bank. He met George W. Griffin, a charmer who squired him

around town. However, it was Hauser in Helena who advised him how to get the job done through a

correspondent bank there. The organization certificate with shareholder signatures was dated February 16,

1884 as submitted to the Comptroller of the Currency’s office in Washington, DC. The First National Bank

of Ketchum, Idaho Territory received its charter allowing it to open once Lewis’ bond deposit of $12,500

to secure a circulation of $11,500 was received by the U.S. Treasurer on March 21st. The bank received

charter number 3142, being the fourth national bank chartered in Idaho Territory after one in Boise City

and two in Lewiston.

Lewis had a 22-foot by 54-foot brick building erected for the bank. He hired George Griffin from

New York City to serve as cashier, who moved his family to Ketchum.

Two private banks already were operating in town. Lewis bought out an operation owned by Judge

T. J. Morgan. along with its furnishings, safe and two lots. T. E. Clohecy & Co. remained a competitor

through 1888.

Lewis served as president for the life of his bank. George Griffin served as cashier from 1884 into

1886 and in that position was the operating officer. Griffin proved to be inept. He gave himself 1-1/2 percent

loans in 1865 and 1866 valued at $2,871.83, absconded to New York and never returned (Ketchum

Keystone, Jul 31, 1885). His 50 shares of stock in the bank were auctioned to partially recover the loss

(Ketchum Keystone, Jun 22, 1889).

Lewis then installed his eldest son Horace Caleb Lewis as cashier and brought in George M. Snow,

Judge Morgan’s son-in-law, as bookkeeper. This combination served through 1889. However, it was

discovered that Snow had been embezzling from the outset bringing the bank to the brink of receivership.

Isaac Lewis made good on the stolen funds thus protecting the depositors

In early 1890, Lewis’ son Horace stepped down as cashier in order to devote more attention to his

Ketchum Fast Freight Line. His younger brother George John—called John—filled the position. Shortly

Figure 4. Horace C. Lewis, Isaac’s eldest son and second cashier of The First National Bank of Ketchum,

preferred mules to banking so established the Ketchum Fast Freight Line in 1884, famous for its 20-mule teams

hauling ore wagons throughout the Wood River region and beyond. Sun Valley Mag.com photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

321

thereafter, Lewis liquidated the bank on April 28, 1890, and it was reorganized as First Bank of Ketchum

under a territorial charter with George J, [John] Lewis & Co. listed as owner (Rand McNally, 1891, p. 148).

Often the incentive for such a reorganization was to allow the bank to make loans on real estate, which was

not allowed under national banking law at the time. This probably applied here because land was central to

the Lewis’ wealth.

First Bank of Ketchum was liquidated in 1897 having paid all its depositors.

Isaac Lewis died May 8, 1903 in Pasadena, California at 78 years, presumably while on vacation

there. He is interred in the family plot in Watertown, Minnesota, he established while living there.

Acknowledgment

Mark Drengson, curator of the Society of Paper Money Collectors Bank and Bankers Data Base,

conducted a genealogical, newspaper and bank directory search that recovered the newspaper articles and

bank directory cited.

Sources

Ketchum Keystone, Jul 31, 1886, Summons (George W. Griffin), p. 3.

Ketchum Keystone, Jun 22, 1889, Bids solicited: p. 3.

Lewis, Isaac Ives, ca 1892, unpublished typescript autobiography: Idaho State Historical Society, Boise,

Idaho, MF 0110.

Minneapolis Star Tribune, Oct 16, 1872, Have struck it rich, p. 4.

Mitchell, Victoria E., 1997, History of the Peacock Mine, Adams County, Idaho: Idaho Geological Survey,

Staff Report 97-14, 23 p.

Rand McNally & Co’s, Jul 1891, Banker’s Directory and list of bank attorneys: Chicago, IL., 534 p.

Figure 5. The First National Bank of Ketchum, Idaho Territory. Ketchum Community Library photo.

(

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

322

Lyn Knight Currency Auct ions

If you are buying notes...

You’ll find a spectacular selection of rare and unusual currency offered for

sale in each and every auction presented by Lyn Knight Currency

Auctions. Our auctions are conducted throughout the year on a quarterly

basis and each auction is supported by a beautiful “grand format” catalog,

featuring lavish descriptions and high quality photography of the lots.

Annual Catalog Subscription (4 catalogs) $50

Call today to order your subscription!

800-243-5211

If you are selling notes...

Lyn Knight Currency Auctions has handled virtually every great United

States currency rarity. We can sell all of your notes! Colonial Currency...

Obsolete Currency... Fractional Currency... Encased Postage... Confederate

Currency... United States Large and Small Size Currency... National Bank

Notes... Error Notes... Military Payment Certificates (MPC)... as well as

Canadian Bank Notes and scarce Foreign Bank Notes. We offer:

Great Commission Rates

Cash Advances

Expert Cataloging

Beautiful Catalogs

Call or send your notes today!

If your collection warrants, we will be happy to travel to your

location and review your notes.

800-243-5211

Mail notes to:

Lyn Knight Currency Auctions

P.O. Box 7364, Overland Park, KS 66207-0364

We strongly recommend that you send your material via USPS Registered Mail insured for its

full value. Prior to mailing material, please make a complete listing, including photocopies of

the note(s), for your records. We will acknowledge receipt of your material upon its arrival.

If you have a question about currency, call Lyn Knight.

He looks forward to assisting you.

800-243-5211 - 913-338-3779 - Fax 913-338-4754

Email: lyn@lynknight.com - support@lynknight.c om

Whether you’re buying or selling, visit our website: www.lynknight.com

Fr. 379a $1,000 1890 T.N.

Grand Watermelon

Sold for

$1,092,500

Fr. 183c $500 1863 L.T.

Sold for

$621,000

Fr. 328 $50 1880 S.C.

Sold for

$287,500

Lyn Knight

Currency Auctions

Deal with the

Leading Auction

Company in United

States Currency

John Douglas, New Orleans Engraver

by Mark Coughlan

Introduction

John Douglas may not be known to those who

collect Confederate Treasury notes, but his name

might ring a bell with scripophilists who are collectors

of Confederate Treasury bonds. Douglas, who ran a

small engraving business in New Orleans, Louisiana,

produced some of the first ever Treasury bonds to be

issued by the newly-formed Confederate States

Treasury department. Secession, and the outbreak of

War in April 1861, had created a sudden business

opportunity for Douglas, but the good times would be

short-lived - in late April 1862, New Orleans was

captured by Federal forces after a surprise and daring

naval attack. So, who was John Douglas, and how did

he go from being a simple high street engraver, making

a living from selling wedding invitations and visiting

cards, to someone who manufactured important

Treasury bonds for the Confederate Government, and

later, Treasury notes for several Southern States?

Ireland

John Douglas was born and baptised on February

10th, 1822, in Rathfarnham, County Dublin, Ireland; he

was the fifth of six children, born to George Douglas

and Rose Kilbride. Rathfarnham, some five miles to

the south of Dublin city, was at that time an area of

beautiful countryside, large Georgian homes, and a

small castle. The area had been settled since Norman

times by wealthy landowners from across the Irish

Sea, and indeed, the Douglas family was of Scottish

descent. Unfortunately, few vital records from the

nineteenth century have survived In Ireland - most

being destroyed in 1922 during the Irish Civil War;

only limited church records are now available, making

research into Douglas’ early life difficult. Dublin

boasted a small, but well-respected engraving

community, and after leaving school, this is most

likely where John Douglas undertook an

apprenticeship (typically lasting seven years), and

later began work.

The Great Famine of (1845-1852) was Ireland’s

darkest time, with more than one million poor souls

dying from starvation and disease due to repeated

failures of the potato crop due to the blight (fungus).

The British Government was heavily criticised for its

ineffective response to the disaster, leading to

increased calls for Irish independence, a collapse of

the Irish economy, and mass emigration. Almost one

million Irish men, women, and children fled Ireland

during this tragedy, mainly emigrating to the United

States; John Douglas was amongst them.

America

Douglas arrived in the United States during the

summer of 1848, aged twenty-seven, and settled in

New Orleans, Louisiana; the city was predominantly

Catholic, and was quickly becoming one of the largest

and wealthiest in the country. By 1851 Douglas had

established his own engraving business, located at 17

Charles Street, in the commercial area of the city, and

built up an appreciative clientele.

The first concrete reference to his business

activities appeared in the New Orleans Crescent

newspaper, dated June 19th, 1852. The newspaper

included the minutes from a meeting of the “Board of

Aldermen” wherein a payment of $16 to John Douglas

was approved for “engraving die and printing”

services. Douglas had engraved a new seal for the city

of New Orleans to commemorate the reunion of the

three municipalities; this was a prestigious assignment

and indicates that he was well respected for the quality

of his engraving work. Advertisements for Douglas’

business appeared regularly from the mid-1850s,

indicating that he was focused on providing general

engraving and printing services.

Figure 1. April 28th, 1857 - Times Picayune.

In 1859, approaching forty years old, Douglas

married Mary Agnes Purcell, aged twenty-four; Mary

had emigrated from County Offaly in Ireland with her

family in 1849. The 1860 U.S. census recorded that

Douglas and his wife had recently been blessed with

their first child, John Jr.; it also revealed that Douglas

was relatively affluent, with real estate valued at

$20,000 and other assets worth some $3,000. Douglas

had acquired several properties in the city as

investments, and this would suggest that he was

already a man of means – with capital - when he had

arrived in America.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

324

Secession and War

Between December 20th, 1860, and February 1st,

1861, seven Southern states seceded from the Union,

and this quickly led to the formation of the

Confederate States of America, with Jefferson Davis

being inaugurated as President on February 18th, 1861.

Within days Davis had formed his cabinet, and the

difficult business of running the new country began in

earnest. The most important challenge was to establish

the military capabilities necessary to protect the

South’s new independence, but this required money.

Thus, the newly-formed Confederate States Treasury

department, led by Christopher G. Memminger,

immediately found itself under intense pressure.

The Confederate Congress, which at that time

was based in Montgomery, Alabama, approved the Act

of February 28th, 1861, providing for a loan of $15

million to finance the immediate priorities of the

government. The loan would be effected through the

issue of Confederate Treasury bonds. Unfortunately

for Secretary Memminger, this was easier said than

done, the problem being that the agricultural Southern

states had always relied on engraving and printing

establishments located in the more industrialised

North for this specialised service. Not surprisingly, the

United States Government, and the citizens of the

Northern states in general, felt considerable frustration

and resentment towards the secessionist Confederate

States, and this impacted trade.

Consequently, Secretary Memminger did not

believe it would be feasible to have his Treasury bonds

produced anywhere in the North. Instead, in a state of

near panic, Secretary Memminger sent agents to scour

the South’s major cities in search of solutions; the city

of New Orleans soon came to his attention, given its

position as the South’s most important financial

centre.

On March 1st, 1861, Secretary Memminger

received a response from one of his agents in New

Orleans – Richard Jones, a partner in a Cotton trading

company – stating that he had attached bids from two

local companies for the engraving and printing of the

required Treasury bonds. One of these bids was from

the New Orleans branch of the American Bank Note

Company, which was headquartered in New York, and

was one of the largest and most respected such

companies in the world.

In his cover letter, Jones specifically cautioned

that under this bid, the required Treasury bonds would

be manufactured in New York City; however, the

attached proposal and quotation provided by the

branch manager – Solomon Schmidt – certainly

implied that the work would be executed locally in

New Orleans. This undoubtedly misled Secretary

Memminger who duly awarded the American Bank

Note Company with a contract to produce a quantity

of Registered Bonds (also known as Stock

Certificates). The work was undertaken in New York.

The second bid was provided by John Douglas,

who ran a small engraving concern in New Orleans.

Whilst Jones had been somewhat dismissive of the

American Bank Note Company’s bid, he was openly

complimentary about Douglas’ capability and his

patriotism, clearly recommending him:

“There have gone forward to you, by Adams

Express, specimens of the engravings of Mr. Douglass,

who is a southern institution and has a high reputation

for ability and faithfulness and executes nearly all the

orders for engraving for the city of New Orleans.”

Jones went on to stress the advantage that

Douglas was located in the South, and also insinuated

that, given New Orleans importance to the

Confederacy, it would be appropriate if he was

awarded a contract.

“From inquiries made, Mr. Douglass may be

relied on, and as we have him, identified with the

South, on the spot, and as New Orleans deserves well

of the Confederation, we hope that he will get the

order.”

It is quite likely that Jones did not appreciate the

complexities of engraving bank notes and bonds in

relation to other more general forms of engraving, and

as such, was perhaps guilty of over-stating the

capabilities of Douglas’ small business. The

Gardener’s New Orleans business directory for that

year (1861) provided a helpful overview of the type of

engraving services offered by Douglas, and it can be

seen that these did not seem to include engraving bank

notes or bonds:

Figure 2. Gardener’s New Orleans Directory of 1861.

Regardless of whether he had any concerns or

not, Secretary Memminger proceeded to award

Douglas a contract to produce some 10-year bearer

bonds (known as coupon bonds) which offered 8%

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

325

interest, maturing on September 1st, 1871. These $50

and $100 bonds – classified as Type 1 and Type 2

respectively in Ball and Simmons 2nd Edition Catalog

of Confederate Bonds – were initially issued from

Montgomery, Alabama, but later from Richmond,

Virginia, after this had become the seat of the

Confederate Government on May 8th, 1861. The

reference to Montgomery on the bonds produced by

Douglas was simply crossed out and overwritten with

“Richmond” by Treasury clerks.

Figure 3. 1861 $50 8% Coupon bond.

Image courtesy of Heritage Auctions.

Figure 4. 1861 $100 8% Coupon bond.

Image courtesy of Heritage Auctions.

Douglas produced these bonds in the typical

format of the day, featuring a single vignette, a central

body of text defining the terms of the bond, and rows

of interest coupons which enabled the holder to collect

the interest due at six-monthly intervals until maturity.

A letter from Secretary Memminger, dated July 24th,

1861, confirmed that Douglas had successfully

completed the order, delivering a total of 8,346 of the

$50 bonds, and 8,016 of the $100 bonds. Between

April and October of 1861, a total of 7,835 of the $50

bonds and 7,950 of the $100 bonds were issued by

Treasury officials across the South. These bonds

proudly bore the imprint: “Douglas. Engr. N.

Orleans”.

Keep the bonds coming!

Secretary Memminger was clearly satisfied with

the quality of bonds being produced by Douglas, and

before work had even been completed on the initial

contract, a second order was placed with him. The

Confederate Congress approved the Act of May 16th,

1861, which authorised a more substantial amount of

$50 million in 8% Treasury bonds, with a twenty-year

maturity date of November 1st, 1881. Treasury records

confirm that Douglas had been instructed to produce

the first $10 million-worth of bonds under this Act, in

denominations of $1000, $500, and $100. In a letter,

dated July 21st, 1861, Secretary Memminger specified

the quantities of each denomination required:

“… let the quantities be 6,000 of $1,000 each,

6,000 of $500 each, and 10,000 of $100 each.”

This in itself represented a lot of work for

Douglas, but in the same letter Secretary Memminger

enquired whether Douglas would have the capability

to undertake the full order - $50 million worth of

bonds. The Treasury’s only other suppliers at that time

were already swamped with other urgent orders,

namely the New Orleans branch of the American Bank

Note Company (which had been renamed as the

Southern Bank Note Company), and the Richmond-

based Hoyer & Ludwig company.

Douglas had begun work on the order, but we will

never know if he would have been able to complete it

successfully. A letter dated August 15th, 1861, from

Secretary Memminger to his contact in New Orleans -

the esteemed James D. Denègre, President of the

Citizens Bank of Louisiana – advised that Congress

wanted to change the terms of the proposed bonds, and

that Douglas should cease all work on them.

Douglas was paid for his work to date on the new

bonds, but unfortunately would not be awarded the

contract to resume work after Congress had agreed the

changes. The contract was handed over to Hoyer &

Ludwig in Richmond, Virginia.

Secretary Memminger had a wariness of the

engraving and printing community, who were known

to be a rowdy bunch, and liked to keep a close eye on

things, especially given the desperate need for the said

Treasury notes and bonds. Thus, he felt uncomfortable

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

326

about the great distance between the engravers in New

Orleans and his office at the Treasury department in

Richmond; this anxiety was compounded by

operational delays with the orders placed with the

Southern Bank Note Company run by Schmidt, and

with the amateurism of another minor New Orleans

engraver, Jules Manouvrier, when a delivery of his

notes failed to reach Richmond securely.

Douglas lands on his feet

Douglas must have been disappointed with the

sudden end to his brief relationship with the

Confederate States Treasury, and the fact that he had

only produced two bonds in their name. Perhaps, as an

act of sympathy and support, he was soon awarded

some work for the City of New Orleans; this involved

engraving four change notes in denominations of 50-

cts, $1, $2, and $3 dollars.

Figure 5. 1861 $2 City of New Orleans.

Image courtesy of Heritage Auctions.

Douglas also produced a set of change notes

(dated November 1st, 1861) for the New Orleans,

Jackson & Great Northern Railroad Co.

Figure 6. 1861 $3 New Orleans, Jackson & Great

Northern Railroad Company.

Image courtesy of Heritage Auctions.

The State of Louisiana

As the War rolled into its second year, the demand

for more Treasury notes and bonds continued to

increase. This demand was not just from the

Confederate States Treasury, but also the Treasury

departments of many Southern States, which were

permitted to issue limited amounts of their own paper

money to supplement that issued by the Confederate

States Government. In early 1862, Douglas was

awarded contracts by the State Treasuries of Louisiana

and Georgia.

The Act of January 23rd, 1862, approved by the

Louisiana State Legislature, authorised the issuance of

change notes in the denomination of $1, $2, and $3;

these notes were dated February 24th, 1862. Douglas is

known to have produced the first series of these notes,

which bore his imprint – “Douglas, N. Orleans”.

Figure 7. 1862 $1 The State of Louisiana (face).

Image courtesy of Heritage Auctions.

These notes were of reasonable quality, similar to

those that he had produced for the City of New

Orleans. Paper was in short supply in the Confederacy

at that time, and Douglas’ notes were printed on the

backs of unused sheets - manufactured in the 1850s by

Draper, Toppan, Longacre & Company of

Philadelphia, and New York - for the Commercial and

Agricultural Bank of Texas, based in Galveston.

Figure 8. 1862 $1 The State of Louisiana (back).

Image courtesy of Heritage Auctions.

A second series of change notes – in the same

denominations, but with much simpler designs – were

issued by the Louisiana State Treasury at this same

time. These notes did not feature an engraver’s

imprint and did not resemble any of Douglas’ prior

notes. If he was involved with them at all, it was

probably only to subcontract the work to another local

engraver.

The state of Georgia

Whilst the notes that Douglas had produced for

the City of New Orleans and the State of Louisiana

were low denomination and of average quality, his

work for the State of Georgia was much more

impressive. The Act of December 5th, 1861, approved

by the Georgia State Legislature in Milledgeville,

authorized the production of $2,500,000 in Treasury

Notes, which were dated January 15th, 1862. Douglas

was contracted to produce the $10, $20, $50, and $100

denominations, which involved a total of some 80,000

notes. This was clearly the most prestigious, but also

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

327

the most challenging engraving work that Douglas had

ever undertaken. The resulting notes were of

admirable quality as illustrated by the two examples

below.

Figure 9. 1862 $10 The State of Georgia.

Image courtesy of Heritage Auctions.

Figure 10. 1862 $50 The State of Georgia.

Image courtesy of Heritage Auctions.

These notes were issued across Georgia between

mid-1862 and mid-1863. Douglas placed his imprint

along the lower right edge of the note: “Douglas Engr.

N. Orleans”.

The fall of New Orleans

In 1861, New Orleans was undoubtedly the

largest, wealthiest, and most important city in the

Confederate States of America, with a population of

almost 170,000. Its location at the mouth of the

Mississippi River on the Gulf of Mexico, made it a

powerful commercial hub; the port of New Orleans

handled half of the South’s cotton exports, a value of

more than $500 million. The city’s importance made it

a prime target for Federal forces, and it was not long

before the U.S. Naval blockade began to hamper

maritime trade activities.

Worse was to come for the city, when on April

17th, 1862, U.S. Flag Officer David G. Farragut led a

daring naval attack on the city from the Gulf of

Mexico, disabling several heavily-armed forts which

defended the mouth of the Mississippi river, and then

sailing upriver where his fleet of seventeen warships

and nineteen gunboats destroyed the smaller

Confederate fleet after a ferocious naval battle.

The Confederate defenders, lulled into a false

sense of security, had been caught completely by

surprise; it was assumed that any naval attack would

be launched via the Mississippi river from the North,

almost 800 miles away. The beleaguered city

surrendered on April 28th, 1862, and was duly

occupied by Federal forces from May 1st until the end

of the War. Not surprisingly, these dramatic events

brought an abrupt end to the bank note manufacturing

activities of John Douglas and New Orleans’ other

engravers.

The War-time economy had undoubtedly

presented John Douglas with a significant business

opportunity, one which he gratefully exploited during

the fourteen months that it lasted. After occupation, his

business returned to normal – wedding invitations and

visiting cards – as an 1863 newspaper advertisement

showed. Federal authorities had quickly declared all

Confederate paper money illegal, and New Orleans

banks were forced to reissue stocks of their own pre-

War notes as a temporary measure.

Figure 11. June 19th, 1863 – The Daily True Delta.

Understandably, the citizens of New Orleans

were wary of the creditworthiness of these old notes,

but Douglas’ advertisement bravely showed that he

had no such reservations.

Douglas’ second child, a girl named Mary, was

born in September 1862, and a third child, another

daughter named Alice, was born in December 1864.

Tragically, his wife Mary would die within days from

complications following the birth of their third child;

the infant, Alice, would also die four months later.

Post-War life and activities

The widowed Douglas and his two children were

surrounded with support from his deceased wife’s

family; in 1866, he married his wife’s younger sister,

Margaret Purcell, then aged twenty. The couple went

on to have six children of their own.

After the War’s end and the subsequent period of

Reconstruction, Douglas continued to operate his

engraving business, relocating in 1866 to new

premises at 10 Camp Street.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

328

Figure 12. January 10th, 1869 – The Times Picayune.

By 1878 Douglas’ son, John Jr., had begun

working alongside him, and the father and son team

remained together for the next twenty years.

John Douglas Sr. died on August 30th, 1900, aged

seventy-eight; he was buried in the family plot at the

Metairie cemetery, at the northern end of Canal Street.

Several local newspapers printed obituaries of

Douglas, all of which were warm and praising of the

stout and genial Irishman from Dublin, who had lived

and worked in the city for more than half a century.

Figure 13. August 31st, 1900 – The Times Picayune.

Douglas was survived by his second-wife,

Margaret, who lived in New Orleans until 1921, and

eight children. His eldest son John Jr., continued the

family business until around 1930, living until 1936.

John Douglas’s last surviving child, Laura, died in

1963, more than a century after her father had issued

some of the first ever Confederate States Treasury

bonds; she was buried alongside her father.

The legacy of John Douglas

There can be no doubt that John Douglas stepped

up to the opportunities that secession and War had

briefly presented him with between February 1861

until April 1862. Had New Orleans not been captured

so early in the War, his activities in producing Treasury

notes and bonds for the Confederate Government and

for individual Southern States, may well have been

more extensive.

However, the question arises as to whether the

bonds and notes bearing the imprint of John Douglas

were all his own work? It would seem to require quite

a jump in skills from engraving simple wedding

invitations to producing tens of thousands of Treasury

notes and bonds. It is conceivable that Douglas was

obliged to engage other specialised engravers to assist

him in completing such sophisticated work, especially

given the extreme urgency involved; piecework and

subcontracting, were common practices in the

engraving industry.

New Orleans was home to several engravers who

were skilled in the production of bank notes and could

have assisted Douglas. These included John V. Childs

(1813-1870), originally from New York, who

produced various pre-War mercantile notes, and

engraved various State of Arkansas Treasury Warrants

during 1861; Childs also produced the famous New

Orleans Postmaster provisional postage stamps prior

to the availability of Confederate States stamps.

Perhaps Solomon Schmidt at the former

American Bank Note Company branch on Royal

Street might also have helped? He is known to have

supplied Douglas with paper and quantities of ink, and

almost certainly loaned many of the pre-engraved

vignettes which appeared on his notes and bonds.

From mid-1861 Schmidt was totally consumed with

his own work for the Confederate Treasury, but he may

well have assisted Douglas with the Treasury bonds

produced earlier in 1861.

Douglas also may have used Schmidt’s facilities

for printing; there would certainly have been periods

when these presses were idle whilst Schmidt was busy

engraving new Treasury notes. But perhaps this is

being unfair on Douglas, and he was able to raise his

game. His obituary claimed that he “… enjoyed a wide

reputation for the finish and perfection of his steel and

copper-plate engraving, which could not be surpassed

by the best foreign talent.”

With such praise, perhaps we should give the

benefit of the doubt to Mr. Douglas. What happens in

N’Awlins stays in N’Awlins.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

329

SOURCES

“Collecting Confederate Paper Money - Field

Edition 2014”: by Pierre Fricke (2014).

“Confederate States Paper Money: Civil War

Currency from the South”: by George S. Cuhaj

(2012).

“Criswell’s Currency Series Vol 1.

Confederate and Southern States Currency”:

by Grover Criswell Jr, (first published 1957).

“Correspondence of the Treasury of the

Confederate States of America”: by Raphael P.

Thian (1878).

“Register of the Confederate Debt”: by

Raphael P. Thian (1880, reprint 1972).

“A Guide Book of Counterfeit Confederate

Currency”: by George B. Tremmel (2007).

“Comprehensive Catalog and History of

Confederate Bonds 2nd Edition”: by Douglas B.

Ball, Henry F. Simmons Jr. (2015).

“Guide Book of Southern States Currency

(The Official Red Book)”: by Hugh Shull

(2006).

“Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era”:

by James M. McPherson (2003).

“The Life and Times of C.G. Memminger”: by

Henry D. Capers (1893).

“Empire of Cotton: A Global History”: by

Sven Beckert (2014).

“Southern Wealth and Northern Profits: As

exhibited in statistical facts and official

figures” by Thomas Prentice Kettell (1976).

“The Great Hunger, Ireland 1845-1849”: by

Cecil Woodham-Smith (1991).

“Confederate Finance”: by Richard Cecil Todd

(1954).

“Dictionary of Louisiana Biography -

Louisiana Historical Association”:

www.lahistory.org

“Origins of the Train Vignette on Confederate

Type-39 Treasury Notes - Paper Money

Mar/Apr 2019”: by Marvin D. Ashmore &

Michael McNeil (2019)

“Historic New Orleans Collection”:

www.hnoc.org

“Gardener’s New Orleans Directory - 1861”

by Charles Gardener (1861).

“Heritage Auctions Online Archives”:

www.ha.com

“Genealogy and History Websites”:

o www.ancestry.com

o www.familysearch.org

o www.fold3.com

o www.findagrave.com

o www.newspapers.com

FURTHER INFORMATION

This short article has been abridged from the Author’s

remarkable new 535-page book on “Engravers and

Printers of Confederate Paper Money”. Available now

in paperback format at $55.00 through

www.amazon.com.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

330

You Collect. We Protect.

Learn more at: www.PCGS.com/Banknote

PCGS.COM | THE STANDARD FOR THE RARE COIN INDUSTRY | FOLLOW @PCGSCOIN | ©2021 PROFESSIONAL COIN GRADING SERVICE | A DIVISION OF COLLECTORS UNIVERSE, INC.

PCGS Banknote

is the premier

third-party

certification

service for

paper currency.

All banknotes graded and encapsulated

by PCGS feature revolutionary

Near-Field Communication (NFC)

Anti-Counterfeiting Technology that

enables collectors and dealers to

instantly verify every holder and

banknote within.

VERIFY YOUR BANKNOTE

WITH THE PCGS CERT

VERIFICATION APP

National Bank Note Circulation

Hit with a Forced 8% Decline

by Redemption of the

Loan of 1925

Introduction and Purpose

The total circulation of national bank notes dropped abruptly by 8 percent in 1925 from $778

million to $716 million. No financial shock had rocked the economy during 1925 to account for this

decrease. Instead, the cause was the result of an arcane technicality: the redemption by the Treasury of a

series of bonds used to secure part of the circulation of national banks that matured on February 1, 1925.

Without the bonds, the impacted bankers had to reduce their circulations until they could purchase other

bonds to replace them. This was problematic because virtually all of the available bonds that carried the

circulation privilege already were tied up by other banks to secure existing circulations.

It is the objective of this article to explain what happened. The spotlight will fall on the Loan of

1925, a 4 percent 30-year loan consisting of U.S. Treasury bonds that originated in 1895. That bond issue

arose from the ill-conceived Series of 1890 and 1891 Treasury note emissions authorized by the Sherman

Silver Purchase Act of 1890.

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act caused havoc to the U.S. monetary system in the mid-1890s.

Then 30 years later, through the maturation of the 1925 bonds, it delt another blow by forcing an 8 percent

reduction in the volume of national bank notes in circulation.

Retirement of the 4 Percent Bonds of 1925

Our knowledge of this story began to unfold when co-author Lofthus happened upon a writeup

warning of the consequences coming with the redemption of the Loan of 1925. The writeup was buried in

the December 1924 Federal Reserve Bulletin (FR Board, 1924, p. 944-947). It led off as follows.

The Secretary of the Treasury has announced that $118,489,900 of 4-percent United States bonds

payable on February 1, 1925, will be redeemed on that date. Over $76,000,000 of these bonds were on

deposit in the Treasury to secure national bank notes on October 31, 1924, and their redemption will

necessarily result in some reduction in the circulation of these notes, since there will not be enough bonds

The Paper

Column

Peter Huntoon

Lee Lofthus

Figure 1. The entire circulation of this Phoenix bank was terminated by the redemption of 4%

Loan of 1925 bonds by the Treasury on February 1, 1925.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2024 * Whole No. 353

332

bearing the circulation privilege outside the Treasury to replace those redeemed. Only about $11,000,000

of such bonds will be left outstanding in the market after the withdrawal of the 1925 issue.

The anticipated reduction of national bank circulation by $65,000,000 or more is about 10 per cent

of the total of notes outstanding.

National bankers were required to deposit U.S. Treasury bonds with the U.S. Treasurer to secure

national bank notes issued to their banks. Congress legislated which bonds could be used, thus endowing

them with what was called the circulation privilege. The eligible bond issues varied over time. Table 1 lists

those that were current in 1924.

The law permitted a given bank to issue circulation up to 100 percent of its capital stock. However,

in 1924 the total outstanding circulation of the country equaled only 54.7 percent of the total capital stock

of all the banks.

The report went on to point out that the total of outstanding bonds bearing the circulation privilege

had diminished markedly since 1914, whereas the total circulation of the national banks continued to grow.

Therefore, the availability of the bonds on the market was severely constrained and declining. As revealed

on Table 1, all but about $11 million worth of the Consols of 1930 and Panama Canal Bonds already were

tied up as security for existing national bank note issues. Once the Loan of 1925 was redeemed in 1925,

there would be an acute shortage of available bonds that the impacted banks could purchase in order to

maintain their circulations. The result was inevitable, most of the bankers who held the 1925 bonds could

not replace them, so they would be forced to contract their circulations. Nationwide, there would be a

reduction of about $65 million or more.

It was pointed out that smaller banks tended to have the largest note issues in proportion to their

capital and they also tended to have the largest share of their circulations secured by the 1925 bonds. This

finding wasn’t surprising because many small banks had entered the system in recent years and their officers

were buying the then available 1925 bonds. See Table 2. However, despite the disproportionate

vulnerability of the smaller banks, the bulk of the circulations secured by the 1925 bonds resided with the

big city banks owing simply to their overwhelming capital.

Origin of the Loan of 1925

A fair question is, what was the origin of the 4% Loan of 1925?

The answer is the ill-conceived Sherman Silver Purchase Act of July 14, 1890, which ran up the

national debt. The act authorized the Series of 1890 and 1891 Treasury notes.

Table 1. U.S. Treasury bonds available and bonds used to secure national bank

note circulations on October 31, 1924.

2% Consols of 1930 2% Panama Canal Bonds 4% Loan of 1925

Total Outstanding $599,724,050 $74,901,580 $118,489,900

Total Used to Secure NBNs $589,086,200 $74,069,640 $76,687,050

% Used to Secure NBNs 98 99 65

Table 2. Loan of 1925 4% U.S. Treasury bonds deposited with the U.S. Treasurer to

secure national bank note circulations on October 31st for the years listed.

1895 $13,856,500 1905 $4,465,000 1915 $32,304,800

1896 $36,531,650 1906 $4,602,100 1916 $26,214,400

1897 $30,474,150 1907 $10,732,900 1917 $34,743,900

1898 $23,990,650 1908 $14,960,450 1918 $50,240,800

1899 $18,242,750 1909 $15,463,050 1919 $58,055,050

1900 $7,503,350 1910 $21,022,650 1920 $68,578,000

1901 $2,911,100 1911 $22,854,300 1921 $77,257,400

1902 $2,208,600 1912 $26,817,000 1922 $82,509,900

1903 $1,410,100 1913 $35,302,700 1923 $85,823,150

1904 $1,791,600 1914 $34,699,300 1924 $76,687,050