William J. Carroll, Gorton-Pew, and the Gloucester National Bank

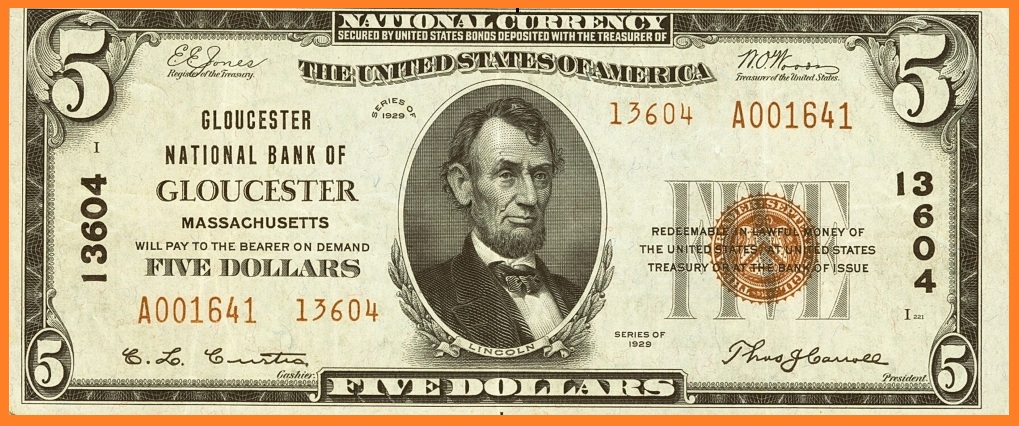

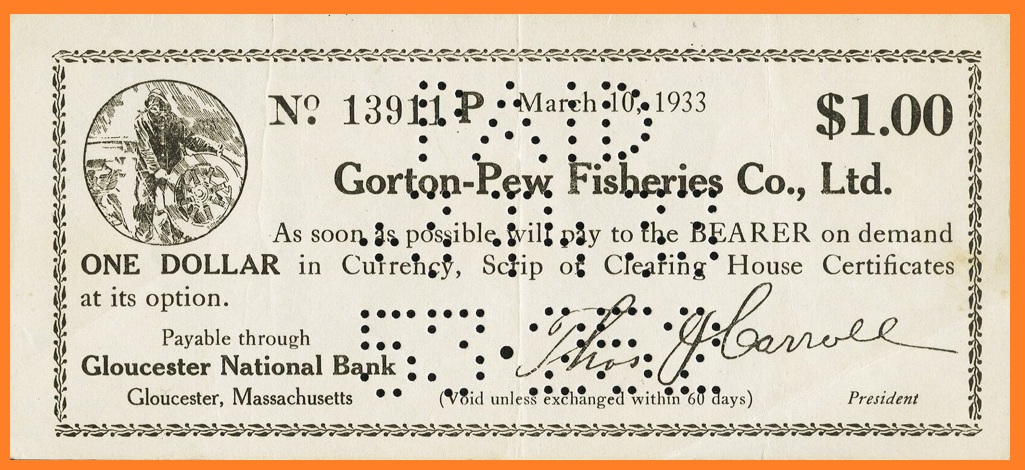

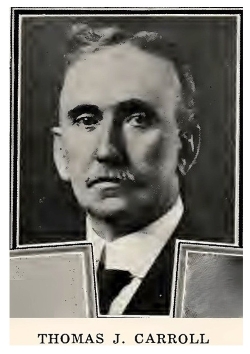

ALTHOUGH EXPERTS reasonably disagree about many things, it is beyond dispute that the frozen fish stick, pioneered by the Gorton-Pew Fisheries Co. of Gloucester, Massachusetts, was one of the most significant consumer food innovations of the 20th century (at least, it was in the household where I grew up). Gorton-Pew also occupies a modest niche in the history of paper money created by the overlapping signatures on the two pieces of paper money illustrated here—one, a banknote on the Gloucester National Bank, the other a piece of depression scrip issued by Gorton-Pew in March 1933. Each piece bears the signature of Thomas J. Carroll, who at the time was President of both the Gloucester bank and the seafood company. A native of Gloucester and from a fishing family himself, Carroll took the helm of Gorton-Pew shortly after it was formed in 1906 and steered the company through the turbulent waters of the early 20th century.

ABOVE: The front of a $5 note of the Gloucester National Bank, signed by President Thomas J. Carroll. BELOW: A uniface $1 scrip note issued by the Gorton-Pew Fisheries Co., of Gloucester, MA, signed by President Thomas J. Carroll (Image source: Heritage Auctions).

Gloucester and the Rise of Gorton-Pew

America’s old fishing port, Gloucester was founded in the early 17th century and maintained a fierce tradition of seafaring independence. At the core of this tradition was the practice of catch sharing, which persisted well into the 20th century. Rather than paying money wages, the fishing business rewarded boat owners and their crews with shares of the fish catch, distributing percentages which varied according to who was responsible for provisioning the ships.

While this traditional practice persisted well into the industrial era, it was modified by three economic developments in the late 19th century which encouraged a consolidation in commercial fishing similar to what was taking place elsewhere in American business life. First, capital requirements in the fishing industry increased as boats grew larger and shifted from sail to steam. In addition, the need to cater to growing consumer markets led to the separation of the actual catching of fish from their processing. Unlike meat and poultry sources of protein, which could be raised and herded even in the absence of refrigeration, fresh fish could not travel far before spoiling, thus limiting its reach to coastal markets. Prior to the development of reliable mechanical refrigeration and freezing technologies, ocean fish could reach large markets only in smoked, pickled, or salted form. Indeed, through the 19th century Gloucester increasingly specialized in the processing of salted fish (primarily cod), while Boston dominated the market for fresh fish. Third and finally, with the expansion of consumer markets came the internationalization of the fishing industry and recurrent clashes with Canadian competitors, who could access fisheries beyond the range of American boats and whose product was often cheaper thanks to their lower costs.

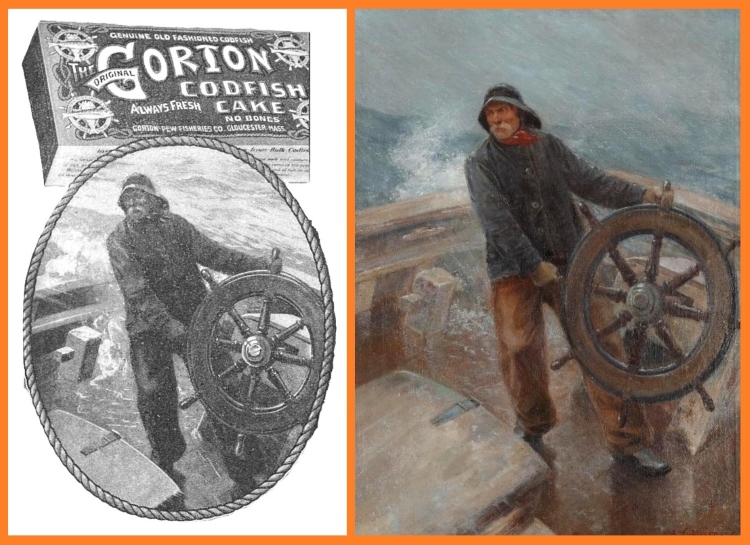

Taken together, these three developments encouraged concentration in the fishing industry, leading to the establishment of the Gorton-Pew Fisheries Co. in 1906. This firm resulted from a merger of four separate family-owned businesses, particularly John Pew & Sons (founded 1849) and Slade Gorton & Co. (founded 1874), the latter notable for having been the first to market branded packages of salted cod directly to consumers. Shortly before the merger Slade Gorton introduced what became the united company’s iconic corporate logo, based upon Augustus A. Buhler’s 1901 painting, “Fisherman at the Wheel” (in 1928, some members of the Gorton family revived the Slade Gorton Co. as a separate, Boston-based wholesale fish supplier). Gorton-Pew’s most popular consumer product in the early 20th century were codfish “cakes” or measured portions of codfish fillets which a housewife could quickly fry up in a variety of ways.

The Gorton-Pew fisherman's logo (left) and the A. A. Buhler painting (right) on which it is based (Image sources: Good Housekeeping, 1910; Collection of Gorton's Seafood, Gloucester).

While maintaining the single biggest fleet in Gloucester harbor, Gorton-Pew did not completely dominate the fishing business there, whose crews otherwise continued to operate on the traditional catch share system. The company also expanded into supplemental business lines like box making, rigging and caulking, and cold storage. Nationally, Gorton’s impact was biggest on the processing and marketing of fish as a consumer product that was an attractive alternative to other protein sources. It continued to sell its packaged, salted fillets under the slogan “no bones”, garnering 80% of the national market by 1918. The company also innovated in the deployment of refrigeration and freezing technologies, launching the first boat with cold storage and freezing capacity in 1913. Marketing frozen fish with consistent quality that was palatable to consumers proved trickier. Although the quick-freezing techniques that made this possible were pioneered in the 1930s by individual inventors like Clarence Birdseye and Newfoundland’s William Hampton, it wasn’t until mid-century that Gorton-Pew led the way in turning frozen fish (and especially the breaded fish stick) into a bland but convenient staple for millions of American consumers.

PISCINE CUISINE: In an era before mechanical refrigeration and frozen fish products, this advertisement suggested one way of preparing Gorton's salted codfish cakes (Image source: Good Housekeeping, 1910).

Thomas J. Carroll, Fishmonger & Banker

Thomas James Carroll (1868-1947) was born into a fishing family, losing his father and a brother in a drowning accident off the Georges Bank. He began on the processing side of the business as a lowly fish cutter but by 1900 had risen to the head of the Gloucester Fresh Fish Co. Carroll later joined Gorton-Pew shortly after the merger and by 1912 was its General Manager as well as President of Gloucester’s Board of Trade. These dual roles sometimes created tension: as head of the Board of Trade Carroll argued the industry’s traditional opposition to free trade in fish with Canada; as President of Gorton-Pew he called for relaxed labor rules that would let him bring in cheaper Nova Scotian fishing crews to Gloucester.  Carroll served as the leader and public spokesman for the industry through the challenges of World War I and the Great Depression.

Carroll served as the leader and public spokesman for the industry through the challenges of World War I and the Great Depression.

War, generally, was good for business as it increased demand for cheap protein, although rising costs and materials shortages hampered operations. German submarine attacks also inflicted losses on Gloucester’s fleets. Most unexpectedly, the war’s biggest impact on Gorton-Pew came in the form of friendly fire. Encouraged by Herbert Hoover ‘s office of Food Administration to fulfill an enormous prospective order by the Italian army, Gorton-Pew was briefly driven into bankruptcy in 1921 when the Italian government refused to take delivery.

Under Carroll’s stewardship, the company was reorganized by 1923. In 1929 he took on yet another role as President of the Gloucester National Bank (charter no. 1162) after the death of its previous President, George O. Stacy. The Gloucester National was a storied institution. Founded as the Gloucester Bank in 1796, it was one of the oldest banks in the country. From the very beginning it catered to seafaring interests. As one profile of the bank put it, “its directors and stockholders were a group of aristocratic old seadogs who carried quarterdeck punctilio into their business transactions.” The bank’s first President, John Somes (1745-1816) was a ship’s captain. After the institution assumed a national charter (no. 1162) in 1865, its first President during the national banking era was Isaac Somes (1780-1873), also a captain. This overlap between bank personnel and prominent fishing families was a common feature of North Shore communities like Gloucester, Rockport, and Cape Ann.

Thomas Carroll assumed leadership of the Gloucester National Bank at a fraught moment. The spreading impact of the Great Depression reached the bank by December 1931, when it was forced to close after the failure of the Federal National Bank of Boston, with which it had connections. Just as he did a decade earlier with Gorton-Pew, Carroll led the effort to restore the bank to solvency, which was reorganized and reopened in March 1932 with the same personnel as the previous bank (now as charter no. 13604) thanks to a recapitalization financed by large depositors. Barely a year later the new bank was engulfed by the national shutdown precipitated by Roosevelt’s bank holiday. In early March 1933 the Gloucester National joined with other banks in Essex County to create the North Shore Clearing House Association with an eye to issuing clearinghouse certificates as an emergency circulating medium. Unlike the banks of the Berkshire County Clearing House Association in western Massachusetts, those nearer the coast never actually printed their own certificates. None of this bank scrip was ever paid out in any case, as the national government soon issued its own, additional supplies of currency.

Unlike banks, non-financial companies of all sorts had to make large payrolls. With the banks closed in early March 1933, Gorton-Pew like many other employers across the country briefly issued bearer checks in small, round denominations that might have some negotiability until companies could regain regular access to their cash. Like the numerous emissions in the mill town of New Bedford to the south, Gorton-Pew’s very functional scrip lacked any adornment other than a facsimile of the company’s fisherman logo. The payroll scrip issued in New Bedford was coordinated by three of the town’s national banks and served multiple employers. In contrast, Gorton-Pew was the only concern to do this in Gloucester. For Gorton-Pew’s President Carroll, it was probably a trivial matter to issue payroll scrip payable through the Gloucester National Bank, of which Carroll was also President.

Thomas J. Carroll remained President and General Manager of the Gorton-Pew Fisheries Co. until he passed away in 1947. The company rebounded after the depression years, expanding its processing facilities into the Canadian Maritimes and otherwise prospering during World War II for the same reasons that it did during the previous conflict. Carroll did not live long enough to witness the miracle of the fish stick, but the freezing technology that made it possible both expanded the role of fish in the American diet and made the fish business fundamentally less seasonal and more globally-oriented than it had been before. Above all, Gorton’s increasingly sourced its fish supplies from global factory fleets that plied ocean waters far beyond the reach of Gloucester-based crews. By the late 1950’s the company refashioned itself simply Gorton’s, thereafter undergoing successive corporate reincarnations until its familiar, fisherman-branded products became a portfolio within a Japanese marine products conglomerate now known as the Nissui Corporation.

.....

REFERENCES

Babson, Helen Corliss, “An Economic and Social Study of the Fishing Industry of Gloucester, Massachusetts” M.A. Thesis, University of Southern California, April 27, 1918.

The Boston Globe, January 21, 1912; January 9, 1929; March 5, 1932; March 19, 1932; March 22 - 23, 1932 (“aristocratic seadogs” quote); June 6, 1947 (Carroll obituary).

Josephson, Paul, “The Ocean’s Hot Dog: The Development of the Fish Stick” Technology and Culture 49 (January 2008): 41-61.

The New York Times, May 23 - 24, 1922; September 25, 1951.

The Wall Street Journal, April 19, 1913; August 23, 1918, May 7, 1954.