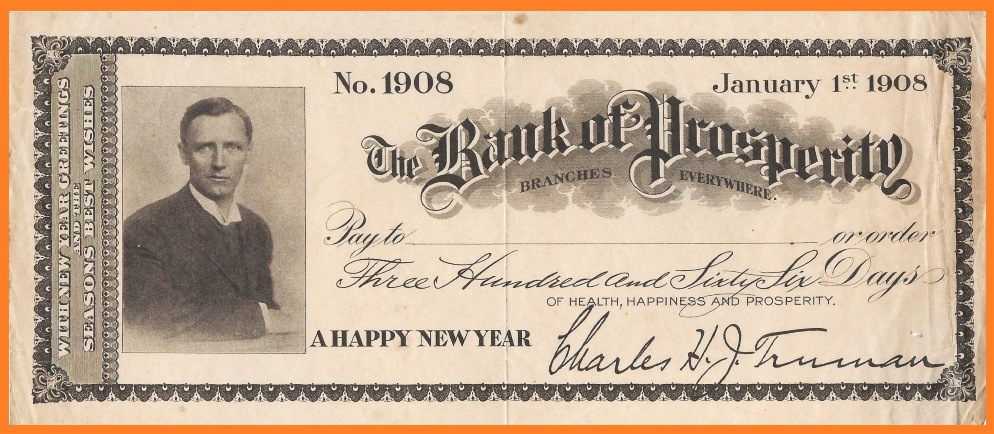

Funereal New Year’s Wishes from Charles H. J. Truman, 1908

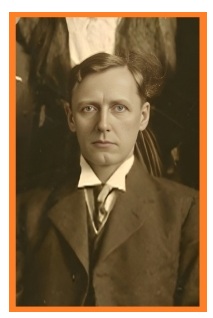

BACK WHEN BANK CHECKS could be as big and ornate as paper money, people commonly sent light-hearted New Year’s salutations by using novelty drafts, typically drawn on the “Bank of Prosperity” and featuring Victorian-era renditions of winged angels, cherubs, or Father Time. Such checks promised to their recipients “three hundred sixty-five” days of happiness, prosperity, or other good fortune. The example illustrated here is distinctive not simply because it dispenses with the usual Victorian embellishments in favor of a portrait of its sender, Charles H. J. Truman, but because of who Truman was. Charles Henry Jacob Truman was a mortician in the San Francisco Bay area who operated a prominent funeral business, the Truman Undertaking Co., along with his son Lloyd, for over forty years.

A New Year's novelty check, customized with the picture of Charles H. J. Truman. Note that it was made out for "Three Hundred and Sixty Six" Days, as 1908 was a leap year (Image source: Author's collection)

A native of San Francisco, Truman was born Charles Henry Jacob in 1871. Receiving his education in local public schools, he later attended Central Wesleyan College in Warrentown, Missouri. He returned to San Francisco and, after a brief stint in advertising, entered the funeral business in 1896 under the name Charles H. Jacob & Co. In 1901 for reasons unknown he changed his last name to “Truman” and thus the company’s to Charles H. J. Truman. That same year he married Alice Therkof, a union that produced two sons and a daughter; the younger son, Lloyd, would later take after his father in the profession. In 1912 Truman relocated his funeral business to Oakland, where he prospered.

Given the inevitability of, and anxieties awakened by, death, success in the funeral industry places a premium on sociability and people skills. These traits Truman seemed to possess in abundance, as he quickly assumed a prominent role in the civic life of Oakland, involving himself in a wide range of charitable, educational, and municipal organizations. Truman’s stature even merited an entry in Ira Cross’s 1927 compendium of financial California, Financing an Empire, thanks to his clutch of directorships in local savings & loans and mortgage banks. Additionally, in 1917 Truman served as President of the California Funeral Directors Association.

Within the history of the funeral industry itself, Truman was something of an innovator. He could lay plausible claim to have conducted, in late September 1907, the first automobile-powered funeral procession (the development of the motorized hearse is usually attributed to the Chicago undertaker H. D. Ludlow in 1909). The circumstances that gave rise to the first known funeral motorcade were a tragic happenstance. Roy Rehm, a well-known California race car driver, died in a competition at the Del Monte track when his 50-horsepower Matheson car blew a tire and overturned at what was then an eye-popping speed of seventy miles an hour. Despite the gruesome nature of the deceased’s head injuries, which prompted other distraught racers to renounce the sport, his fans, friends, and fellow enthusiasts declared that it was only fitting if Rehm's coffin were conveyed to its place of eternal rest in a contraption like the ones he so loved to drive. Thus ensued what may have been the world’s first funeral motorcade. The San Francisco Chronicle of September 25, 1907, described the unprecedented scene thus:

Dead Racing Man Borne to the Grave on a Motor Car Hearse

“An automobile funeral, the first of its kind ever held in San Francisco, attracted a great deal of attention on the streets of the city yesterday morning. The funeral was that of Roy Rehm, the crack automobile racing driver who met his death in the wreck of his car in the race meet of the Automobile Club of California at Del Monte on Saturday afternoon. An automobile delivery car was arranged as a hearse, and upon this the casket containing the body of Rehm was placed, as is the coffin of a soldier on a gun caisson. The casket was almost entirely hidden by great masses of flowers, which had been sent by the many friends of the dead racing man and by the various automobile associations. The lines of the car itself were hidden by crape [sic] drapings.

The casket was placed on the motor hearse at undertaking parlors at Mission and Fifteenth streets [Truman’s facility] and from there the procession of automobiles went to the Wesley Methodist Episcopal Church at Hayes and Buchanan streets. Immediately following the hearse was a limousine car, with the curtains drawn, containing the relatives and immediate friends of the racer. Forty to fifty cars chugged slowly along in line. Down Valencia street to Market the procession went, and then down Market as far as Van Ness avenue. Then it turned up to Golden Gate, and slowly wended its way out the automobile avenue to Buchanan street, and then across to the Wesley church. Thousands of persons lined the streets as the strange and unusual procession passed along, and the windows of houses were filled.

The body was taken into the church and the services were held. Music was given by a full choir. The minister commented on the speed of human life, stating that all people worked and played with too great a rush and energy, to the neglect of the better things of life. After the services the cars were driven to Cypress Lawn Cemetery, where the remains were interred. The funeral was under the auspices of the California Chauffeurs’ Association, of which Rehm was a member.

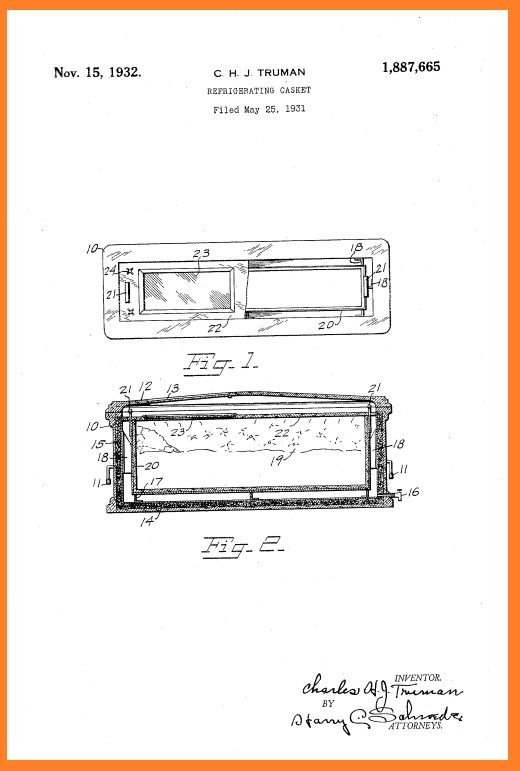

For Truman and other funeral directors, such vehicular conveyances quickly became the norm. A 1939 newspaper profile of the Truman Company, marking the fortieth anniversary of its operations, bragged that its “beautiful homelike mortuary is elegantly appointed with Georgian colonial furnishings and its Cadillac and Packard motor fleet is the finest available.” By that time Charles Truman’s younger son Lloyd was serving as Vice President of the company; among the staff included four licensed embalmers (three men, one woman). Charles Truman’s business flair also revealed itself in his inventiveness. Truman came up with the idea for a “Refrigerating Casket.” Presumably the intent of the casket was not to provide comfort to its inhabitant, but to delay the olfactory side effects of decomposition. If so, it was an invention better suited perhaps for hotter and more humid climates than that of the Bay area. Truman filed for and received a patent for his invention in November 1932.

The schematics for Truman's patented "Refrigerating Casket" (Image source: Google Patents).

Not that Truman H. J. Truman would have meant the gesture mordantly, but anyone receiving an example of his New Year’s check would have gotten greetings from someone whose business required its recipients NOT to have “three hundred sixty-five” days of good fortune upon this earth—if not that year, at least as some point in their mortal lives. Truman himself, who in the march of time became his business’s own customer, passed away in 1940 while attending a conference of funeral directors in Indianapolis. After burying his father, Lloyd Truman continued with the company until it was wound down in the late 1970s.

REFERENCES

Cross, Ira B., Financing an Empire. History of Banking in California Vol IV (S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1927), pp. 70-73.

Oakland Post-Gazette, September 14, 1939.

“Refrigerating Casket” Patent No. US1887665A

https://patents.google.com/patent/US1887665

San Francisco Examiner, May 6, 1901.